For almost 40 years, Isla Roberts has resided in Mylor in the Adelaide Hills with Susan Phillips-Rees. While having tea in their kitchen, Isla shares the story of how they first met through a song.

waiting for her train

The initial instance I encountered Susan, she was positioned by a gate, anticipating her train’s arrival.

Holding a bridle in her hand / and a smile on her face

In 1984, Phillips-Rees was in need of someone to transport a horse. Roberts was known for being skilled with animals and was soon invited to the home Phillips-Rees had purchased with her former spouse. Although Roberts was already married, she ended up moving in within a year.

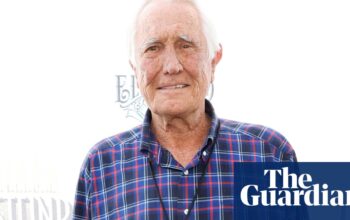

“It’s a natural occurrence,” explains 87-year-old Roberts. “When you have feelings for someone, you may decide to live together.”

The kitchen walls display fragments of the unlikely yet intersecting tales of Roberts and her twin sister, Barbara. Among them are monochrome pictures of the two riding horses, appearing identical. Also featured is a captivating portrait of Phillips-Rees, drawn in the 1970s by a then-young Robert Hannaford – a reminder of a previous cosmopolitan existence.

Their relationship is clearly well-established, but if you try to label it or discuss Roberts’s sexuality, she will not tolerate it.

At the start of Isla’s Way, a recently released documentary tracking their lives for a year, she declares, “I am not a lesbian. I am Isla Roberts!”

Documentarian Marion Pilowsky, who is embarking on her first project, is faced with a dilemma. This situation may seem outdated, as labels like these are now commonly embraced by members of the queer and marginalized communities as a way to form connections and establish their identities. As Pilowsky attempts to explain the concept of “coming out” to an uninterested Roberts, their dynamic is reminiscent of a time when discreet terms like “friend” were used to refer to various lifestyles and relationships that were not openly acknowledged.

-

Join us for some exciting content in our weekly roundup of essential reads, popular culture, and weekend advice, every Saturday morning.

The 80-minute documentary, filmed by Roberts’ own David Magarey Roberts, allows her life story to slowly unfurl as she tends to horses, potters around, and shares a lot of laughter and occasionally some tears.

Roberts was two months pregnant when she married her late husband at a registry office, before moving out to a sheep station 600km north-west of Adelaide where she dug wells, raised four children and lived with an increasingly unstable man. The film-makers follow her to the ruins of that house laid waste by time and the elements (“It was awful, I’ll never go there again,” she says of the experience).

I delicately inquire if the thought of cohabiting with a woman and having a similar type of relationship as Phillips-Rees was ever a consideration during her marriage.

She states firmly, “No, no, no.”

Phillips-Rees was residing in Sydney and had a bright future as a social worker when her spouse, who was a creative director at a well-known global advertising agency, accepted a position in Melbourne. “I never even considered saying, ‘If you go there, I’ll stay here and continue with my job.’ It was just the way things were back then.”

Ignore the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

Kuala Lumpur, London, Somerset and Singapore would follow, where Phillips-Rees would have a range of experiences – “those Indian girls, you know, in Singapore,” she says – before the marriage collapsed. In the film, Phillips-Rees is frustrated by Roberts’ rejection of the “lesbian” label, which she feels negates their connection.

Roberts’ life contains elements that delve into common themes of aging, self-sufficiency, and liberty. The camera documents her strong will to keep driving despite opposition from her grown children – a challenging discussion that many families can relate to.

However, there is a significant distinction in Roberts’ situation: she is discussing carriage driving, which she developed a love for as a child growing up in the countryside alongside her late friend Barbara. Throughout the documentary’s year-long storyline, Roberts’ efforts to demonstrate her capability to physically control the reins at her grandson’s wedding are a major focus.

“There’s nothing I am incapable of doing,” she declares with determination. “If I have the desire to do so.”

During the interview, Roberts and Phillips-Rees mentioned that they had not yet watched the film. They plan to save it for the premiere at the Adelaide film festival before it is released in theaters. During the early stages of filming, Phillips-Rees expressed enthusiasm for the film as a way to combat the lack of representation of older women and lesbian grandmothers.

Currently, she is feeling fatigued from being under constant examination for a whole year. She is preparing herself for the possibility of her family and neighbors witnessing all the details presented on the large screen.

She laughs as she exclaims, “I will not be able to stroll along this cursed road!”

Roberts appears satisfied with not overanalyzing the movie or her personal life and remains determined to not let her emotions and encounters define her – both the struggles and the peaceful moments of liberation.

She states, “I am not inclined to discuss myself. I have had a satisfying life. I possess the ability to bring humor and laughter to anyone.”

In regards to their situation at home, there may be certain words that Roberts is content to use.

She expresses, “Living with Susan brings me great happiness. It’s truly a joy to be her roommate.”

Source: theguardian.com