L

The Michael Werner Gallery is located on a street near London’s Park Lane and exudes an air of sophistication and wealth in the art world. Tucked away in a Georgian townhouse, it is so discreet that one would not notice it while passing by. It comes as no surprise that the late Don Van Vliet’s paintings are displayed here, as Michael Werner has been his gallerist since the 1980s, when Van Vliet shifted his focus from music to visual art. However, his paintings in this recent London exhibition seem out of place in this elegant setting.

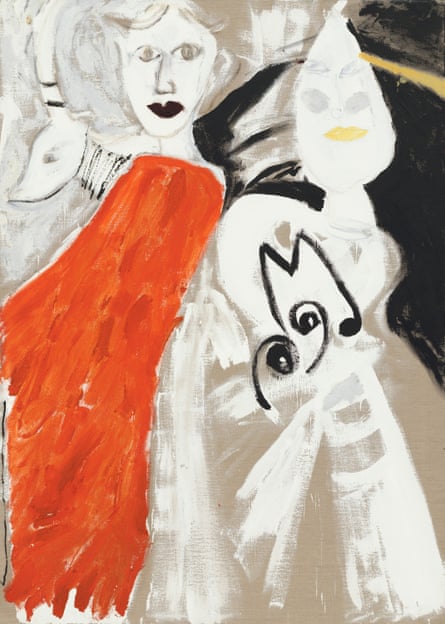

One of the reasons for this is that they are clearly influenced by the natural landscapes of California, where Van Vliet spent time living and working in the Mojave desert. His paintings often feature wild animals and cacti, but as his career progressed, they became overshadowed by the environment around them. The later works are characterized by large areas of blank space, almost as if they have been bleached by the intense sunlight. This may also be attributed to their energetic and unrefined style, with wild brushstrokes, thick layers of paint, and direct application from the tube. However, above all else, these paintings are unmistakably the creations of Captain Beefheart, a highly revered figure in 1960s and 1970s rock music, regardless of any name changes.

The titles often reflect his previous songs or lyrics: those familiar with the tracklist of his 1969 masterpiece Trout Mask Replica will identify the title China Pig, while Crow Dance a Panther and The Drazy Hoops are derived from lines in Ice Cream for Crow and The Blimp. Even when they do not directly relate, they have a similar feel: Dream Sloth, Full Grown Babble, Bird With Cotton Shadow. And, just like his unique blend of blues and free jazz in his music, these titles defy categorization and have been a challenge for people to classify.

As I read about his art journal, I notice critics making various comparisons to famous artists such as Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock, as well as different art movements like expressionism and primitivism. However, Gordon VeneKlasen from the Michael Werner Gallery clarifies that the artist, Don, cannot be categorized as an outsider artist because he was not naive in his approach. Don was well-informed about the history of art and was very deliberate in his choices and words. Even in their conversations, Don was precise and careful in everything he did and said, which was reflected in his paintings.

The tale of how Don Van Vliet transitioned from Captain Beefheart, renowned avant garde musician, to a visual artist began well before he adopted his well-known pseudonym and founded the initial version of the Magic Band. From a young age, Van Vliet showed exceptional skill in sculpting, earning awards and even appearing on television to showcase his animal sculptures. According to his own recollection – although he was not always the most reliable narrator of his own life – he was offered a scholarship to study art in Europe at just 13 years old. However, his parents forbade him from pursuing it, citing their belief that art was “strange”.

Throughout his music career, he continued to create paintings that were featured on album covers and displayed in a 1972 exhibition in Liverpool. However, his artwork was often overshadowed by his music. With the release of Trout Mask Replica, Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band’s sound was truly unique and extraordinary. Even now, 54 years after its debut, it is consistently recognized as one of the most challenging albums of all time. Each instrument seems to exist in its own universe, with only a loose connection to the others. While some critics argue that it does not qualify as music, devoted fans hail it as a work of unparalleled genius. John Peel described it as possibly the only true work of art in the history of popular music. For John Lydon, it was a defining moment that opened the door for limitless creativity.

AR Penck, a fan of the artist Don Van Vliet, was represented by Michael Werner. According to VeneKlasen, when Penck defected to the west in 1980, he repeatedly urged them to find Van Vliet, whom he considered his true hero.

Penck’s idea posed a challenge, even though Werner was impressed by Van Vliet’s artwork and suggested that he be represented by him. According to VeneKlasen, “having two careers” is now a common occurrence, but in the 1980s, it was seen as ridiculous to be both a musician and a painter. The creation of art was seen as serious and respectable, while making music was viewed as something completely separate.

It is unclear who proposed that Van Vliet should stop making music altogether, abandon the name Captain Beefheart, and focus on painting. There are several stories surrounding this decision – one claims that Werner and Penck suggested it, another suggests it was his wife Janet, and a third states that it was solely Van Vliet’s own idea. This was likely prompted by the fact that no record label was willing to fund a follow-up to his 1982 album “Ice Cream for Crow,” which, as was typical for Captain Beefheart, received critical acclaim but poor sales. However, regardless of whose idea it was, Van Vliet did not require much convincing. According to reports, he was exhausted and discouraged by his career in music – he had already cancelled a planned tour and was struggling financially, living in a trailer that was previously owned by his mother. VeneKlasen recalls, “He had been mistreated by the music industry, so he ultimately decided to give it up completely and pursue painting. He was not a bitter man, but he held resentment towards the music business.”

Possible rewording:

One might speculate if there were additional reasons behind his choice to leave the music scene. Van Vliet’s interactions with his bandmates were frequently tense. Multiple former members of the Magic Band have referred to him as “tyrannical”, and Zoot Horn Rollo’s book Lunar Notes portrays their time together as constantly miserable: impoverished, barely surviving on a daily diet of soybeans, and subjected to their leader’s psychological manipulation, which sometimes escalated to physical aggression.

Ignore the newsletter advertisement.

after newsletter promotion

A possible interpretation is that Van Vliet had a unique artistic vision that revolved around creating highly intricate and challenging music, and he was determined to achieve it at any cost. However, VeneKlasen notes that it is easier to pursue a singular artistic vision when you are the only one doing so. She also mentions that Van Vliet was very controlling, despite the fact that his music involved other people. As he got older, he became less fond of interacting with others. On one occasion, when I visited him in Eureka, California, I found that he lived in a remote area. It seems that painting held more appeal for him, as it allowed him to work on his own without the involvement of others.

However, there were challenges in Van Vliet’s transition to a new career despite his commitment. VeneKlasen attempted to persuade him to move to New York, but was met with the response that the city had too much “human skin” in the air and was simply a “bowl of underpants.” While his early shows were popular among Beefheart fans, the mainstream art world was not as accepting. In fact, a museum director who curated a show for Van Vliet faced almost losing his job due to the backlash from others in the art world who saw Van Vliet as a musician rather than a legitimate artist. It wasn’t until 10 years after his death that there was a shift in perception, largely thanks to other artists appreciating Van Vliet’s work. Charline von Heyl, a German abstract painter, even shared that she looks at Van Vliet’s work every morning for inspiration. While curators at prestigious institutions may dismiss his work, other artists hold it in high regard.

Until his death in 2010 due to complications from multiple sclerosis, Van Vliet continued to work. As his illness progressed, the gallery created a device for him to paint from his armchair, but he eventually switched to drawing. He never returned to his music career. According to VeneKlasen, Van Vliet was known for his fierce and uncompromising nature. He did exactly what he wanted and that was the end of it. He was a true product of the California era, when there were bombings and construction of highways. In fact, VeneKlasen recalls a story where Van Vliet worked as a vacuum cleaner salesman and even sold one to Aldous Huxley.

He chuckles, but then remembers Van Vliet’s tendency to create myths about himself and his sometimes questionable relationship with the truth, and adds a caveat. “I didn’t verify the accuracy of it. I should probably check and see where Aldous Huxley resided during that time. But as a tale about California during that era, I found it incredibly compelling. It’s reminiscent of Brave New World, and it’s just strange. California was definitely a bizarre place.”

Source: theguardian.com