A

Chris Kamara, a football commentator on TV, was a one-of-a-kind individual. While he possessed a great knowledge of the sport, that wasn’t what made him so beloved. Rather, it was his infectious smile and booming laughter that endeared him to fans. He had a knack for finding the humor in everything, especially in himself. Fans also loved his unique sayings, such as when he described Tottenham Hotspur as “fighting like beavers” in one match report. He was known for shouting “Un-be-lie-va-ble!” or sometimes “Un-be-lie-va-ble, Jeff!” from the stadiums where he was reporting back to Jeff Stelling on Sky Sports’ Soccer Saturday.

Kamara was highly regarded for his oversights and omissions. On a notable Saturday in April 2010, he was reporting on a match between Portsmouth and Blackburn. The show’s host at the time, Stelling, announced, “We’re heading to Fratton Park, where a red card has been given. But who was it for, Chris Kamara?” Kamara appeared confused. While most pundits would try to bluff their way through, Kamara was honest. “I’m not sure, Jeff!” he responded. “There was a red card? I must have missed that. Was it a red card?” He gazed at the field, still unaware of what had happened.

“Have you not been paying attention?” Stelling inquired. “What has occurred, Chris?”

Currently, Kamara appeared similar to a student who has been caught skipping class by their principal.

“I’m not sure, Jeff!” He burst into laughter, his mouth stretched wide. “I’m not sure. Maybe the rain got in my eyes, Jeff!”

Stelling instructed him to use his fingers to determine the remaining number of players on the field. Kamara’s voice became high-pitched. “I actually saw him leave, but I assumed they were substituting another player, Jeff.”

“Kammy, you continue to impress with your professionalism,” Stelling praised. “Your reports on Gillette Soccer Saturday are always cutting-edge!”

In the studio, his colleagues who analyze football were laughing uncontrollably. Amazing.

During Kamara’s commentary, it was always entertaining, regardless of the game’s intensity. However, in 2019, something changed with his voice that he had relied on for twenty years. It became slower and developed a harsh croak. He struggled to speak and his thoughts seemed disconnected. He sounded as if he had suffered a stroke. Kamara was afraid, but kept it to himself, not telling his wife, sons, friends, or coworkers. He feared it could be the beginning of Alzheimer’s disease. “It felt like someone else was speaking through my vocal cords. This would happen for about three hours a day, and then my voice would return to normal.”

Did Anne speak at all? “No,” he replied with a smile. “I was clever. I would only talk in short statements or soundbites. Engaging in long conversations was not a good idea.” During the times when his voice was giving him the most trouble, he would avoid being around on his small farm. “When my voice was very hoarse, I would stay quiet and wait until it improved before speaking again.” However, it wasn’t just his voice that had changed. “I would go down to tend to the horses and sheep, but I started losing my balance and stumbling. Simple tasks that I used to do without thinking, like using the wheelbarrow, suddenly became a challenge.”

Initially, it was simpler for him to conceal the situation since football was cancelled at the start of lockdown. However, as soon as the games resumed and Kamara appeared on TV, he began to feel anxious. It was at this point that he noticed his reports becoming less clear as he started to mix up his words.

Kamara recently published a new autobiography titled Kammy: My Unbelievable Life. In it, he recounts a game where he realized he was struggling. He was unable to perform his duties. He explains, “My tongue felt swollen and hanging out of my mouth. My trademark smile disappeared. I was sweating heavily and had a hot, prickly sensation on my back.” This sounds frightening, I comment. “Yes, it was. Absolutely. I was at Barnsley that day and I knew my speech was impaired on the way there.” He called an old friend who couldn’t understand him. He lied and said it was a bad connection, one of many lies he told to hide what was happening.

During the game, when Stelling approached him for an update, he struggled to speak. His heart was racing and he had never experienced anything like it before. It felt like his heart was about to burst out of his chest and he couldn’t articulate his thoughts. Even now, revisiting the memory brings back traumatic feelings. He tried to keep his commentary brief when a goal was scored. Surprisingly, no one on the team mentioned his struggle, so he assumed no one noticed. He began to doubt the severity of the situation and wondered if it was all in his head. In the end, he pushed through and moved on.

During the period of quarantine, he reported on games from the lesser known leagues in the northern region. As doubts arose about his ability, he falsely claimed that his lack of knowledge of the players’ names was to blame. Whenever he was posed a question, he would ask for it to be repeated in order to gather his thoughts and articulate them accurately.

K

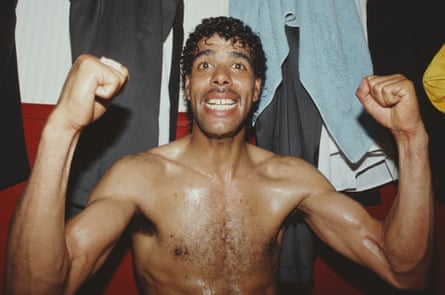

Amara is conversing with me from his residence in Wakefield. His appearance remains unchanged – a large, cheerful countenance, pencil-thin mustache, and a smile that resembles a lottery win. However, it is only when he speaks that one can detect a change.

At the age of 65, the individual had a noteworthy but not particularly prestigious career in the sport of football. He competed in over 600 league games with nine different clubs, including Portsmouth, Swindon, and Brentford. Starting off as an attacking midfielder, he eventually transformed into a tough defensive midfielder. In a rare and unexpected moment, he became the first English player to be found guilty of causing serious injury during a game after punching another player and breaking their cheekbone. This behavior was completely out of character for him. The individual, who had previously faced racial abuse during the same match, considers this incident to be the lowest point of his career. Despite his talent, he never had the opportunity to play for his country and declined an offer to compete in the 1994 African Cup of Nations for Sierra Leone (a country he was eligible to play for through his father).

Kamara’s success in football could be considered a miracle, given his upbringing in Middlesbrough during a time when the National Front and racism were prevalent. On the Park End estate, where he and his family were the only black residents, Kamara’s father Albert was one of the few black men in town. Unfortunately, Albert was often wrongly accused and arrested by the police for crimes he did not commit. The Kamara family also faced discrimination from their neighbors, who often blamed them for any issues on the estate.

Albert didn’t care about football and only watched his son play once in school. A football coach named Alan Ingledew took him to watch Middlesbrough and Leeds play at home on alternate weeks. Albert wanted his son to join the navy, just like he did after finishing school. When his son was 16, he was noticed by the youth team manager of Portsmouth while playing for the navy team. However, even when he played well, he was booed by the National Front supporters in the Portsmouth crowd. When he joined Swindon a couple of years later, he received death threats from Portsmouth fans and had to be escorted by police to the County Ground. But he never let it bother him.

At 36 years old, he became a player-coach for Bradford City in the second division (third tier). After manager Lennie Lawrence was fired in 1995, the team was at risk of being demoted. Kamara, who had been promoted from assistant manager to caretaker manager, made a bold promise to chairman Geoffrey Richmond. He casually said, “I’ll get us promoted,” without truly believing it. However, he knew he had to convince the chairman who had just given him the job. Against all odds, the team went on a winning streak, made it to the playoffs, and ultimately won the final to secure a spot in what was then known as the first division.

What were the standout moments of his professional life? “As a child, my goal was to play for Middlesbrough and my ultimate dream was to play for Leeds. To accomplish both was truly incredible. Another memorable moment was leading Bradford to victory at Wembley for the playoff finals. I walked out onto the field as a manager, hand in hand with my sons who were mascots. It doesn’t get much better than that.” He was one of the pioneering black managers in the top four divisions of English football. His promotion to the second division made him the most successful black English manager, a title that was only surpassed when Chris Hughton led Newcastle to the Premier League in 2010. In his previous autobiography, “Mr. Unbelievable,” Kamara noted how few opportunities were given to black managers to showcase their skills. “Even today, there are very few black faces in management roles,” he says.

In the next season, he managed to prevent being demoted by winning the final game, but was fired the following season. In January 1998, he became the manager of Stoke City, but only won one out of 14 matches and was let go. Kamara had believed he had a successful career ahead as a manager, but quickly realized how unpredictable football chairmen could be.

I was contacted by Soccer Saturday, a new show with a unique format that had never been attempted before – for good reason. Who would want to watch former footballers staring at a screen, with Kammy reporting on the game with his back turned? However, it turned out to be a success and became a staple in the world of football. When they asked me to join, I hesitated and asked, “Are you sure?” Why? Because the other panelists were all legends – George Best, Rodney Marsh, Frank McLintock, Alan Mullery. They were all great guys, especially Bestie who was the kindest person you could ever meet. They never made me feel inferior and welcomed me into their group, allowing me to be myself.

He takes a moment to reflect. “I often wonder what would have transpired if social media existed during my time. Would they have attacked me and questioned my presence on there, like they do with some women nowadays?” I interject, expressing that there are many layers to this statement. Why do you believe you would have been attacked? “I didn’t have a successful playing career like them.” He explains that back then, it would have only taken a few individuals to deem him incompetent rather than humorous for his reporting career to come to an end before it even began. “It could have been too much for a company like Sky to handle.”

Does he believe that the treatment of women like Alex Scott and Jill Scott is purely based on misogyny? After a long pause, he responds, “Um… yes. Yes, in Jill’s case, and for two reasons in Alex’s case.” Is it both misogyny and racism? “Yes.”

Kamara greatly enjoyed his time on Soccer Saturday. In 2000, he began hosting Goals on Sunday (formerly known as Soccer Extra), where he analyzed the previous day’s matches. He also became a frequent guest on the TV show Soccer AM, where he conducted unconventional interviews with football players. As his popularity grew, he started to branch out and host other shows such as Ninja Warrior UK and Cash in the Attic. He even made appearances on Have I Got News For You and The Great Sport Relief Bake Off, and made cameo appearances as himself on Emmerdale and Ted Lasso. Kamara’s presence in commercials also added authenticity and humor, whether it was for aluminium doors, shampoo, or controversial gambling ads. Despite some backlash from viewers about the gambling ads, Kamara’s iconic catchphrase “unbelievable” and infectious laughter was all it took to entertain audiences. He even released a successful Christmas album. With his various ventures, Kamara had become a versatile entertainer and was thoroughly enjoying life. But then his voice began to fail him.

Skip over the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

The idea of writing match reports caused him to feel unwell. People on social media began to notice that something was not right. Some expressed concern, while others mocked him. After appearing on his friend Steph McGovern’s show, Steph’s Packed Lunch, one tweet stated, “Before having Chris Kamara read the Autocue, someone should have checked if he is able to read.” During a match between Huddersfield and Bristol City, he stumbled on the steps of the gantry and feared he would fall. A steward remarked, “It reminded me of my father.” This comment deeply hurt him, but he quickly made an excuse, claiming he had slipped before and was being cautious. That night, his friend and Sky colleague Tony Gale called and asked, “Are you okay, Kammy? You don’t seem like your usual self.” Once again, he made an excuse, saying he was overworking and tired.

One of the most challenging moments for him was during his appearance on The One Show to advertise his second holiday album. He struggled to speak and couldn’t recall the album’s name or its songs. On the way home on the train, a familiar conductor asked him how he was doing, but he still couldn’t form coherent sentences. The conductor kindly left him alone, assuming he had a few drinks.

He recalls performing in a Christmas show with Paddy McGuinness, where he sounded as if he had consumed 10 pints of alcohol. People were discussing it, but he didn’t mind. He would rather have them think he was drunk than having a speech impediment. He takes a moment to pause and reflect. He expresses regret for not being able to handle his condition properly and apologizes to anyone who struggles with speech or neurological issues, realizing that it does not define them as a person. He now feels ashamed for being ashamed of his condition in the past.

Did he believe that the culture of football was so focused on masculinity that he couldn’t bring himself to acknowledge the vulnerability that comes with having a brain condition? “Yes, absolutely. That’s exactly right. And I never did it my entire life, whether it was dealing with racism or injuries. You just push through it. That’s how I was raised. That’s my mindset. You don’t play the victim, you have to toughen up, and you don’t show your emotions to the public, teammates, or managers. To anyone. It wasn’t until I developed this condition that I realized how wrong I was all those years. Completely wrong.”

He developed a fear of speaking, both on and off camera. Despite telling others that everything was fine, maintaining this facade must have been draining. “It was messing with my head. Every day, I wondered if I would be able to speak. When the delivery man came to the door, could I even hold a conversation with him? The person I used to be would have cracked jokes and had a good time with him. But now, I feel like a stuttering old man who can’t articulate himself. My self-confidence was at an all-time low and that’s when strange thoughts start creeping into your mind.”

Kamara loved his job as a broadcaster and thought he would have it for a long time. He was thrilled to transition from playing and managing for 24 years to being on TV. It was like a dream come true. He just had to be himself and have fun. However, when it was suddenly taken away, he felt like he lost a part of himself. He couldn’t believe it and wondered where he went. He didn’t like the person he had become. These thoughts weighed heavily on his mind.

During the times when he would visit and spend time with the animals, he found himself plagued by dark thoughts. These thoughts told him that he was a burden and that his family would be better off without him. This occurred during the peak of his condition, 18 months in, when he believed he was suffering from dementia. He didn’t want to impose on his family, especially since he had spent his whole life taking care of them.

How serious was his intention to end his own life? “It was just a thought. I wasn’t actively planning an exit. I just knew that if something happened, I wouldn’t be too upset about it.” Eventually, Kamara decided to seek medical help. He was initially diagnosed with an underactive thyroid, but was later diagnosed with apraxia of speech, a neurological disorder that affects the brain’s ability to produce speech. While he was relieved to not have Alzheimer’s, he immediately thought about having to quit his broadcasting career. Despite this, he couldn’t bring himself to share his condition publicly. He convinced himself that he would tough it out until the end of the season and then quietly leave. But why was he so afraid? “I didn’t want people to pity me. I didn’t want to be seen as a victim.” Kamara brings up this fear several times during our conversation. It becomes clear that being pitied is one of his biggest fears. He mentions his hypnotherapist, Daniel McDermid, who told him, “The day you start accepting your condition is the day you start getting better.” Kamara replied, “I accept that I am receiving treatment from you, but I cannot go public with it. I don’t want to be seen as a victim.” To this, McDermid responded, “You’ll be surprised,” and he was right.

He shared his experience with apraxia in an interview with his co-presenter Ben Shephard on ITV’s Good Morning Britain, whom he considers a close friend. He was initially hesitant, but eventually agreed to go on the show. The experience turned out to be the best day of his life, as he was amazed by the support and empathy shown by people. It finally helped his fans understand his condition.

Kamara left Sky after Stelling announced his departure on Soccer Saturday, which brought the anchor to tears. Although Sky did not try to persuade him to stay, other TV shows eagerly offered him a position. Last year, he created a moving documentary for ITV called Lost for Words, which focused on his condition. He also appeared on The Masked Singer earlier this year. Kamara now has numerous job offers, almost as many as he did before his condition developed. Recently, a company informed him that they would need to alter his voice for a commercial. Despite his initial concern, Kamara no longer worries about hiding his condition and is open about it with potential employers. He acknowledges that he is not the same person he was before, but he embraces the new version of himself.

After Kamara made his situation known to the public, he expressed feeling like a sham as a broadcaster because he could no longer fulfill his job duties. However, he has since received an overwhelming amount of support, particularly at a Middlesbrough game where fans displayed banners with messages like “You’re not a fraud, Kammy. You’re incredible.”

He now wishes to repay the trust and affection shown to him by advocating for others who also have apraxia. His goal is to raise awareness of the condition and inspire those who suffer from it to live fulfilling lives despite their challenges. However, he acknowledges the importance of not trivializing the struggle: “I don’t want anyone to think that after spending two years in denial, I’m now saying to be yourself and speak out about it. I understand that, but I can only share from my own experience. I was able to persevere because everyone stood by me and said, ‘We don’t care how you speak, you’re Kammy and we love you.'”

The assistance helped him realize his fortune. Not everyone has access to it, and there are others who have been much more ill than him at a younger age. “I am determined to do whatever I can to assist children who are born with speech difficulties. In our country, those with verbal dyspraxia only receive one appointment with a speech and language therapist, and then they may have to wait six months or even a year for the next one.” Last month, he delivered a speech at the House of Commons in an effort to increase support for speech and language therapy for children in need.

Kamara is currently making every effort to assist both himself and others. In the past year, he traveled to Mexico for a new form of treatment that had not previously been utilized for individuals with apraxia. He reports that it has led to significant improvement. While his speech is still slow and monotone, it is much more fluid than it was at its worst. Though it may not have the same level of excitement as before, some of the emotion is returning. Most importantly, Kamara states that his brain has begun to reestablish the correct connections: even if the words take longer to surface, they are now the correct ones.

Initially, it was communicated to me that he would only be able to converse with me for 45 minutes, but in the end, he ended up talking for an hour and a half. By the end of our conversation, he was nearly ecstatic about the possibilities. He explains, “I thought I was finished. I couldn’t even form a coherent sentence. The connection between my thoughts and my speech just wouldn’t work. But now, that flow and fluency is present.” He acknowledges that there is still a long way to go, but he is pleased with the progress he has made. In his book My Unbelievable Life, he states that he is back to 75% of his pre-apraxia state. When asked what percentage he would say he was at his lowest point, he responds, “At my absolute lowest, I was essentially at zero. When I was feeling down with the horses and in the fields, contemplating giving up, having these terrible thoughts, I was at a complete loss. Looking back now, I realize what a foolish notion that was. How could I have entertained such thoughts? It’s absurd. But now I have a better understanding of mental health and I recognize that there was a voice inside me pushing me to seek help. Those thoughts were ridiculous!” He emphasizes the word vehemently, as if trying to erase any trace of that idea from his mind.

His enjoyment of life has been restored, which is the most significant change. Will he be willing to provide live updates for sports matches once more? I anticipate him dismissing the notion, but he now seems to believe that anything is achievable. “If I continue to make progress, then absolutely!” His face lights up with a familiar, nostalgic Kammy grin.

The book “Kammy: My Unbelievable Life” written by Chris Kamara will be released on November 9th by Pan Macmillan for the price of £22. To show your support for the Guardian and Observer, you can purchase a copy through guardianbookshop.com. Additional fees for delivery may apply.

.

Samaritans can be reached at 116 123 or via email at [email protected] in the UK and Ireland. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be contacted at 800-273-8255 for support via chat. Additionally, individuals can text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis text line counselor. Australians can call Lifeline at 13 11 14 for crisis support. For other international helplines, visit www.befrienders.org.

Source: theguardian.com