T

Middle-aged black humanities professor Helonious “Monk” Ellison, residing in Los Angeles, is not well-liked by his students or colleagues. He has written several unsuccessful novels that draw on classical mythology. Struggling with his career and financial concerns, including caring for his elderly mother with dementia, Monk becomes further disheartened upon seeing the success of a new novel by black author Sintara Golden. The novel, titled “We’s Lives in da Ghetto,” seems to cater to the stereotypical portrayal of illiterate black victims, which is often favored by white cultural gatekeepers. In a fit of anger, Monk writes a parody novel about hood violence called “My Pafology,” under the pseudonym Stagg R Leigh, and submits it to his agent with the assumption that its blatant crassness will convey its satirical nature. However, things take an unexpected turn, reminiscent of the Broadway production “The Producers,” involving Max Bialystock and Leo Bloom.

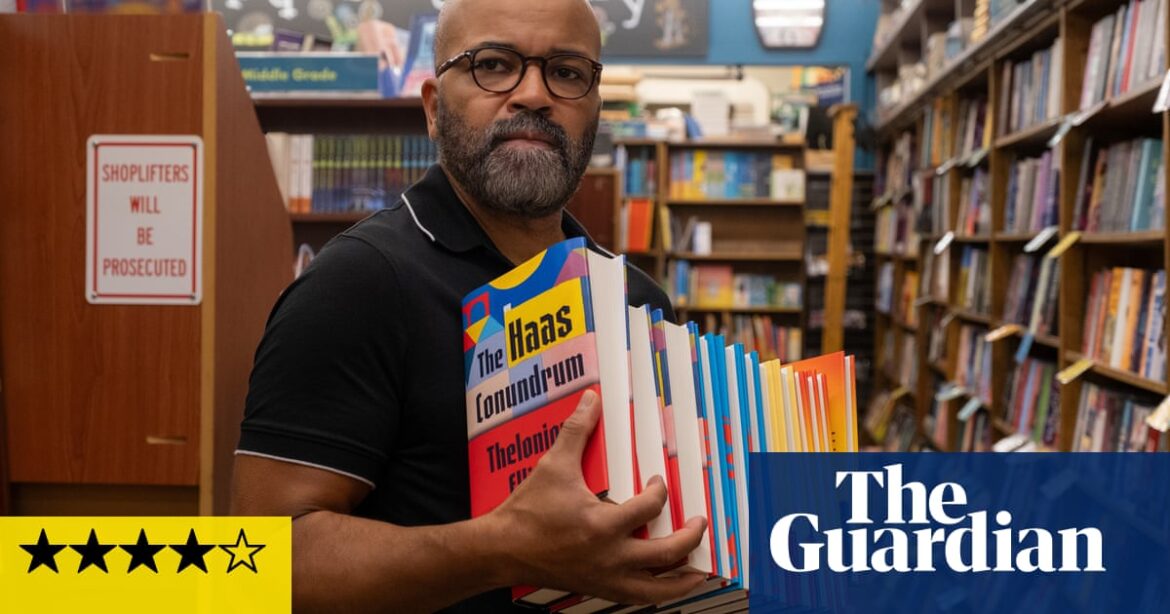

American Fiction is a humorous new comedy in the literary world by filmmaker Cord Jefferson. It is the first feature film he has directed, based on his own adaptation of Percival Everett’s 2001 novel, Erasure. The talented Jeffrey Wright stars as Monk, a character who is sensitive, melancholic, and idealistic in a self-destructive manner. Tracee Ross Ellis plays Monk’s clever sister Lisa, while Sterling K Brown portrays his brother Cliff, a cosmetic surgeon who recently came out as gay. Leslie Uggams delivers a touching performance as Monk’s mother, Agnes, and Issa Rae plays Sintara Golden, Monk’s rival. Despite some minor changes made by Jefferson, the film is highly enjoyable.

American Fiction manages to overcome a challenging obstacle, which was more openly tackled by Michael Winterbottom and Frank Cottrell-Boyce in their 2006 film adaptation of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, titled A Cock and Bull Story, or by Harold Pinter in his 1981 screenplay adaptation of John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman. These adaptations aimed to realistically capture the original works’ levels of metanarrative. However, Everett’s novel includes the complete text of My Pafology in its middle section, allowing readers to fully delve into it, recognize its absurdity and exaggeration, appreciate its exhilarating enthusiasm, and perhaps even consider if the author contemplated writing a bestseller like it but ultimately settled for including it in quotation marks.

When translating this to film, Jefferson may have considered the option of making Monk, the main character, a sophisticated professor of film studies. In this version, Monk’s “My Pafology” would not be a novel, but rather a screenplay for a movie similar to “New Jack City” (which is mentioned in the story). At the end, Jefferson explores these ideas and creates a humorous and captivating fantasy about how social class, race, and literary preferences intersect. It also serves as a cautionary tale about the irony of societal standards and the absurdity of career failure. Additionally, it offers a cynical examination of literary jealousy: Monk’s angry imitation of We’s bestselling book “Lives in da Ghetto” reminded me of Kingsley Amis’ account in his memoirs of feeling insecure about a rival’s success and briefly considering imitating their style.

Pass over the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

In one instance, Jefferson creates a conflict between Monk and Sintara where Sintara defends her novel, which may be seen as a loss of satirical commentary. The author’s name in the book is also a parody. Despite this, Wright and Rae deliver the scene convincingly and portray Monk’s snobbishness towards Sintara’s success, possibly influenced by gender. There is a comedic element when Monk has to publicly pose as the notorious Stagg R Leigh, but this is not too different from the real-life situation of author Laura Albert, who was exposed in 2006 for creating a fake persona, JT LeRoy, who wrote gripping stories based on her supposed traumatic life experiences. Albert even had her sister-in-law wear a wig and sunglasses to portray this reclusive literary genius. (It should be noted that the book Erasure was written before this incident.)

While American Fiction may have a general approach, its handling of race and racism is subtle and surprising. Additionally, it cleverly addresses the publishing industry’s literary segregation with humor.

Source: theguardian.com