I

In January of 1985, the Smiths are preparing to release their politically charged album, Meat Is Murder. The NME article from December 1984 gives a sneak peek into the album with the sincere inquiry, “Instead of writing about oneself in general terms, your latest songs seem to focus on specific situations…” Morrissey’s influence has led to a rise in vegetarianism among students nationwide. This issue is treated with great gravity.

In Smash Hits, Tom Hibbert’s initial inquiry to the singer is, “What is the issue with you?” Hibbert speculates that Moz’s constant fatigue could be attributed to his vegetarian diet’s “daily consumption of yogurt and bread.” He interrogates him about his idols’ eating habits and the food he provides for his cat, and concludes by posing the hypothetical question, “If you were to pass away tomorrow and meet Colonel Sanders from Kentucky Fried Chicken in heaven, what would you say to him?” Morrissey suggests a kick in the groin. Hibbert notes that this is a trick question: “You should have responded that Colonel Sanders would not be in heaven.”

“Oh.”

This Q&A, focused on a single issue, serves as a perfect example of the Hibbert approach. In the 1980s and 1990s, he employed a religious dedication to facts and utilized absurdism in order to deflate pretentiousness. He also used these techniques to determine whether celebrities were aware of their fortunate circumstances. Surprisingly mundane questions often led to revealing answers, such as asking what color Tuesday was. At times, he would not even ask questions, instead choosing to sit back and smoke while his interviewees squirmed and gave away more information than intended. His writing style often utilized a conspiratorial language, reminiscent of PG Wodehouse and Geoffrey Willans’ Molesworth but with a touch of psychedelic flair. Despite the seemingly frivolous subject matter of teen pop music, Hibbert’s writing attracted a generation of devoted readers who appreciated his serious approach to a genre that is often not taken seriously.

Hibbert’s absence may have resulted in the absence of Popworld, Popjustice, and the Guardian Guide (may it rest in peace). However, his ability to expose illusions of grandeur may have contributed to the PR-driven crackdown that took the fun out of celebrity journalism once he was finished with it. (Ringo Starr stormed out of one of Hibbert’s interviews, outraged that “this is a true legend in front of you”). Almost 13 years after his passing at 59, his impact remains prevalent. Mark Ellen, a friend, colleague, and co-founder of Q, recalls, “I was listening to the Today programme the other day and Amol Rajan used a phrase coined by Tom Hibbert when describing a political story – ‘… and it all went horribly wrong!'”

Display the image in full screen mode.

The book “Phew, Eh Readers?” is a compilation of Hibbert’s written works, ranging from his early essays on his admiration for the band The Byrds to his made-up letters for New Music News, a magazine that was created during a strike by NME and Melody Maker in 1980. It also contains essays written by Hibbert’s friends and colleagues. Pete Selby, the publisher of Nine Eight Books, was a dedicated reader of Smash Hits starting in 1981. He was particularly excited when Hibbert joined the magazine a few years later and helped it reach its peak. Selby recalls that Hibbert’s unique perspective on all things dear to him greatly resonated with him.

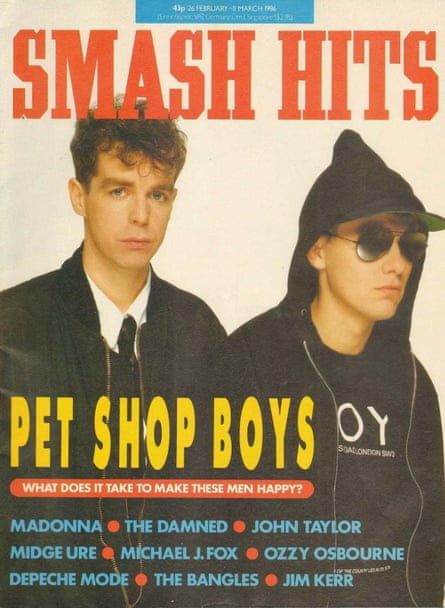

Neil Tennant, who was then the assistant editor of the magazine (and would soon become part of the Pet Shop Boys), provided Hibbert with an opportunity. Hibbert had previously worked for DIY publications and attempted a career as a musician before joining New Music News. He had also authored the well-received and self-explanatory book Rare Records in 1982. Ellen was also employed at New Music News but left for Smash Hits when the temporary magazine was struggling. Tennant requested that Hibbert contribute some reviews. Upon reading them, Tennant remarked, “Who wrote these? They’re incredibly amusing,” according to Ellen. One of the reviews was a satirical play featuring three boring men with expensive stereo equipment discussing their tweeters and woofers, and using the new Genesis single to test them out. It was a clever piece of writing.

Display the image in fullscreen mode.

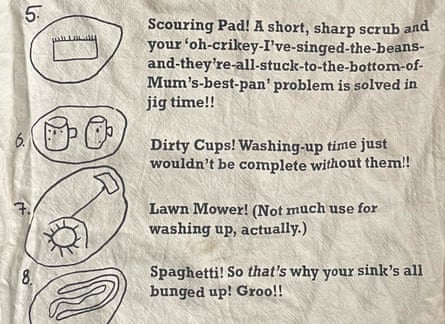

When Hibbert joined Smash Hits in 1983, he elevated its unique voice even further, according to Tennant. His quirky style added a touch of eccentricity to the magazine. Outdated musicians were referred to as “the dumper,” alcohol was playfully called “sauce” or “rock’n’roll mouthwash,” and the use of quotation marks was a form of irony. The letters page was overseen by a mysterious figure named Black Type, who was believed to be created by Hibbert himself. Ellen recalls that Black Type would come out at night when everyone had left and respond to letters with clever and psychedelic comments. As a reward for the best letter of the week, readers would receive a tea towel with Black Type’s name on it – a prize that seems fitting for Hibbert’s offbeat style.

When Ellen saw Hibbert’s perspective, she remembered that his father, the well-known historian Christopher Hibbert, had come to Tom’s garden in Fulham and inquired, “How do you maintain such beautiful flowers?” Tom replied, “Just a little fertilizer and water, and some tender loving care.”

“I adored the concept that these artificial daffodils had flourished in a world where humans had created such elaborate fantasies.”

Hibbert was known for his creativity, but according to his co-worker Chris Heath, they were extremely strict about accuracy. Many people assume that content geared towards teenagers is not important and can be made up, but we aimed to recognize the ridiculousness and triviality in everything while also treating it with the utmost seriousness.

See the image in full screen mode.

Sylvia Patterson relocated from Perth, Scotland to join Smash Hits in 1986. She impressed Hibbert during her job interview by expressing a preference to meet Stan Cullimore from the Housemartins over Madonna. Meeting Hibbert was a “heroic” experience for her. They collaborated on the Bitz front section, with Hibbert mainly focused on his work. Patterson was inspired by his ability to amuse himself with his own jokes, as she believes great comic writers should. She enjoyed seeing what he would come up with, as he never wrote based on anyone else’s guidelines. His “complete creative liberty” influenced Patterson (who has been making music journalism a more humorous place for almost 40 years). He gave her and others the confidence to develop their own voice without being constrained by rules. She carried this mindset with her throughout her career.

In the late 1980s, nine-year-old Nadia Shireen lived in Bristol and was a big fan of Smash Hits. She was influenced by her older brother and they would write letters to each other using the language from the magazine. They even created a fanzine about their family using this language, which Shireen now finds humorous. From 2002 to 2004, she worked at Smash Hits in production, despite the magazine’s decline. Today, Shireen is a successful children’s author and illustrator, and she still sees the influence of Smash Hits in her work. In her book The Bumblebear, some bees are surprised to discover that their new bee friend is actually a bear in disguise. The line “What the jiggins!” from this book was inspired by a headline from a Smash Hits feature about Morrissey. Shireen admits to unintentionally borrowing it from the magazine.

Display the image in full screen mode.

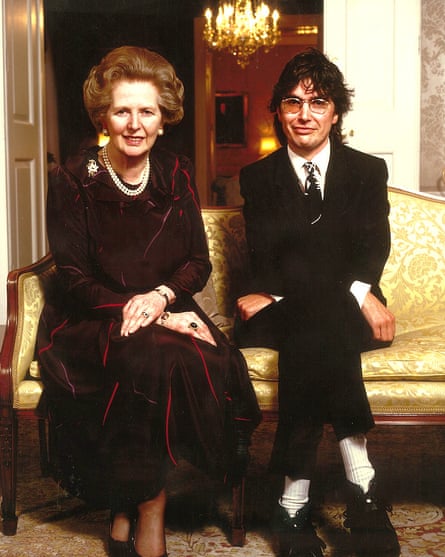

Hibbert’s influence was significant enough that in 1987 (while wearing a borrowed suit), he conducted an interview with Margaret Thatcher for Smash Hits. Her team was eager to have him, representing the youth of the nation, supporting her cause and reaching out to the magazine’s 800,000 readers. However, Hibbert was not swayed by her evasive answers and was able to detect her attempts at deflecting questions. Her lengthy and exaggerated responses were filled with common Smash Hits phrases such as “(???-Ed)”, revealing her disconnect with the younger generation.

Hibbert was feeling frustrated with Smash Hits and decided to take up the offer from Ellen and David Hepworth to join the new Q magazine in 1987. According to Ellen, Q had an overall positive tone, but they wanted to add some substance, so they created the recurring Who the Hell? feature for Hibbert to interview the less self-aware celebrities of the time, such as John Lydon.

Ignore the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

The profiles demonstrate a keen perception of insincerity and unwarranted self-importance – Roger Waters unintentionally addressed the question “Are you the most pessimistic man in the world of rock?” by declining to answer it – while also expressing disappointment at the lackluster offerings presented to young listeners as the music charts became increasingly commercialized. His delicate approach is admirable: when Status Quo make derogatory remarks towards women, gay men, and Italians, he simply remarks, “The Quo doesn’t seem to have strong ideological beliefs, do they, readers?” (However, Hibbert’s eerily prophetic 1990 Q profile of Jimmy Savile, in which he raised the question of Savile’s rumored fascination with dead bodies and received the response “I am not a necrophiliac”, was not included in the new book to avoid overshadowing it, according to editor Jasper Murison-Bowie.)

Q successfully carried out these executions by deceiving PR representatives into believing that their clients were being interviewed by another writer, only to substitute in Hibbert at the last moment. According to Tennant, Q was bold and unafraid, and even after years of being approached for interviews, the Pet Shop Boys’ PR would still question if it was for Q’s publication. Tennant believed that the band could benefit from the exposure.

Following his time with Q, Hibbert proceeded to write an unconventional music column for the Mail on Sunday and an even more peculiar one for the Observer, chronicling his unsuccessful attempt to join the now-defunct Whig party. However, in 1997, he was hospitalized for pneumonia and acute pancreatitis, and spent four months in a medically-induced coma. According to his widow Allyce Hibbert, he never fully recovered from this experience. After three years, she relocated to Hong Kong, feeling hopeless due to Hibbert’s refusal to improve. He never returned to work and passed away in 2011. “It was a terrible situation,” writes Allyce. “Everything came rushing back. But then I was able to start liking him again, without having to face the reality of him.”

In the late 1990s, Hibbert’s impact was decreasing. The magazine Smash Hits, which I used to read as a child, shut down in 2006 and had a flashy style. Pop music was becoming more artificial and public relations firms were gaining more power. Interviews in serious newspapers that were meant to be confrontational lacked Hibbert’s ability to foresee the “amazing possibilities” of the world, as described by Heath.

Popjustice, a website created by Peter Robinson in 2000, stood out for its unconventional take on pop culture. Robinson was driven by a desire to challenge the prevailing views of the music industry, where mainstream media praised all pop music while more serious outlets dismissed it entirely. This led to a lack of credibility for both sides. Popjustice found allies in the edgy Stool Pigeon newspaper and Channel 4’s Popworld, where interviews were often conducted with megaphones in a parking lot. Unfortunately, Popworld came to an end in 2007 due to its lack of respect towards celebrity guests.

Display the image in full screen mode.

In today’s media landscape, interviews with popular music icons have become increasingly rare and often overly complimentary, making one question the dynamics at play. According to Michael Cragg, who wrote Reach for the Stars, an account of British pop between 1996 and 2006, the power dynamic has shifted in favor of the stars, especially with the rise of social media allowing direct communication with fans. Additionally, there is now a demand for pop stars to address more serious issues, contradicting the idea that pop music should be celebrated with the same level of sincerity as rock music.

In the 1980s, there was a sense of innocence surrounding the emergence of pop stars through MTV. However, in today’s society, there is a greater awareness of mental health and the potential for abuse in the music industry. This can make it uncomfortable to mock certain pop stars. Additionally, there are fewer opportunities for satirical features in pop magazines, as well as a lack of camaraderie among journalists due to the decline of these publications. In light of Condé Nast’s recent layoffs at Pitchfork, therapist and media trainer Robinson suggests that hiring full-time music journalists dedicated to improving one publication can help maintain a consistent tone and high quality content.

Currently, there are still individuals who carry on the legacy of Hibbert: Heath is in charge of editing the Pet Shop Boys’ yearly publication, Annually (obviously), which is filled with fascinating facts. One recent inquiry from a reader asked if Tennant and Chris Lowe have ever ridden a horse: Tennant: no; Lowe: one donkey, and not just any horse but Paul McCartney’s horse. In the upcoming issue, Heath hints at a segment discussing whether they put on socks or pants first – ultimately useless information that surely adds to the joy of nations. Cragg’s Reach for the Stars celebrates the intricate details of a glimmering era in pop culture that many may not deem worthy of close examination. Shireen has sold two authorized replicas of the Black Type tea towel by Ellen, with the proceeds from the second one going towards the victims of the Manchester Arena bombing. It wasn’t until I read a previous collection of Who the Hell? articles 12 years ago that I realized how much Hibbert language I had picked up from my older friends. And it is widely acknowledged that quotation marks indicate irony.

Heath expressed his delight upon learning about the new Hibbert collection. He believes that voices like Hibbert’s are often overlooked, as people who provide analytical analyses of popular culture are typically more celebrated. While the era of Smash Hits may be seen as a time of 80s nostalgia, Heath sees it as a significant and influential platform for discussing culture, celebrity, and the world. He considers himself fortunate to have started his career there, surrounded by intelligent, sharp-witted individuals who created something truly intriguing. Despite the chaotic and frenzied nature of their work, they approached it with careful thought and intelligence.

Hibbert once expressed his admiration for Alex Chilton by stating: “There are not many heroes left.”

Source: theguardian.com