South Africa’s ruling African National Congress party has lost its three-decade electoral majority in devastating fashion. As the former liberation movement faces the task of building a coalition government, it remains to be seen how it will respond to the message sent to it by voters.

The ANC’s vote share collapsed from 57.5% in 2019 to 40.2% in last week’s elections, amid chronic unemployment, degraded public services and high rates of violent crime. The party also lost control of three of South Africa’s nine provinces, including KwaZulu-Natal where the impact of the former president Jacob Zuma’s new party, uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) – which surprised with 14.6% of the vote nationally – was felt most keenly.

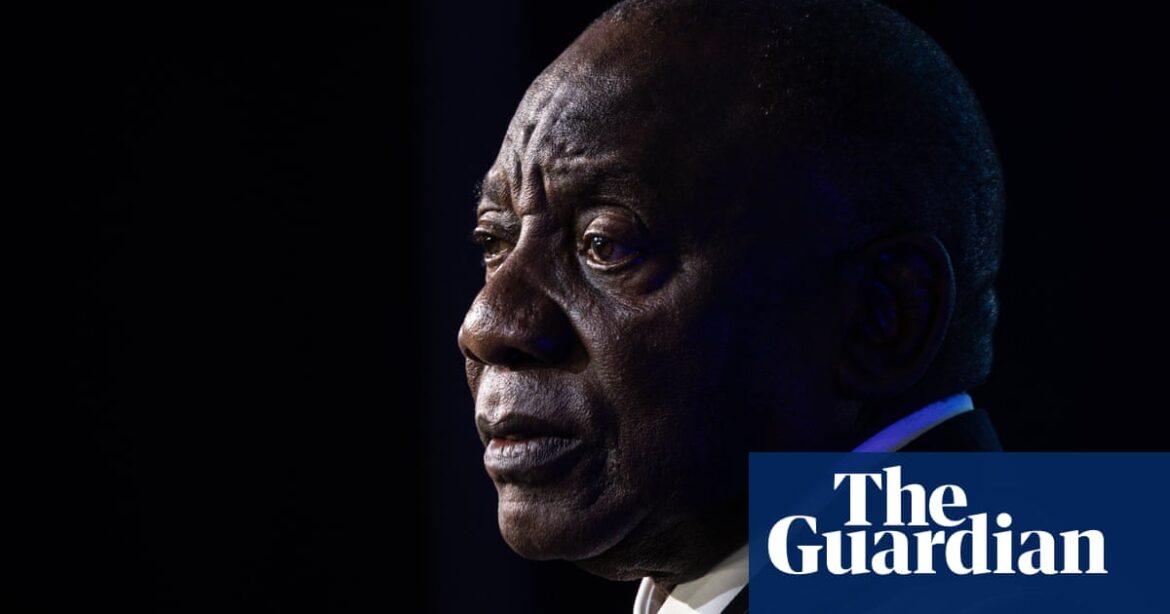

South African president, Cyril Ramaphosa, who senior ANC officials have said is going nowhere, sounded a conciliatory note in a speech at the election results centre on Sunday night after the final tally was announced. “Our people have spoken; whether we like it or not, they have spoken,” he said, adding that South Africans expected political parties to work together and find common ground.

A national coalition government has arguably been inevitable for years, with support for the ANC – which swept to power under Nelson Mandela at the end of apartheid in 1994 – declining in every national election since 2009.

“They were seen as the party that had ushered in liberation, freedom,” said Kealeboga Maphunye, a professor of African politics at the University of South Africa. “But then they started becoming very relaxed, taking their voters for granted, being arrogant even.”

Maphunye pointed to statements such as “I didn’t join the struggle to be poor”, infamously attributed to an ANC spokesperson in the mid-2000s. “Where did it go wrong? It’s precisely things like this and, of course, the wanton corruption that crept into the ANC,” Maphunye said.

Ebrahim Fakir, an analyst at the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa, said voters had not necessarily punished corruption, pointing to the vote share of the ANC and Zuma’s MK.

Many MK voters claimed life was better under Zuma, even while experts have said the rot in state institutions set in under his presidency. A judicial inquiry alleged that Zuma fired competent officials, appointed loyal ministers and influenced the awarding of large contracts while leader from 2009 to 2018. This was in order to benefit the Indian businessmen brothers Atul, Ajay and Rajesh Gupta, the 2022 Zondo commission report said, in a scandal known as “state capture”.

Zuma, 82, who has waged a bitter feud with Ramaphosa, 71, since being ousted as president by the ANC, is due to go on trial next year on charges that he took bribes from the French arms manufacturer Thales in 1999. Zuma pleaded not guilty in the Thales case and has separately said the “state capture” allegations were part of a conspiracy against him.

Some ANC members support going into coalition with the MK, which wants to replace constitutional democracy with parliamentary supremacy, and the Marxist-Leninist Economic Freedom Fighters, formed by the former ANC youth leader Julius Malema in 2013 after he was expelled from the party.

“They genuinely think ‘if we add the three of us, we’re close to 60 (per cent share of the vote). So let’s get back together – we’re all in the same party, we’ve just got a different emphasis’,” Fakir said. “Well that’s not true … There are fundamental disagreements,” he said, pointing to opposing views between parts of the ANC and the MK and EFF on everything from nationalising South Africa’s central bank to seizing land from white farmers to redistribute among poorer black people.

The choice of which parties to go into coalition with is the big question awaiting the ANC, said Melanie Verwoerd, a former ANC MP. The more pro-business wing of the party is reported by local media to be favouring a tie-up with the white-led, second-placed Democratic Alliance and the smaller Zulu nationalist Inkatha Freedom party (IFP).

Verwoerd noted that the ANC had lost about 2m votes to the MK and a further 2m to the lower turnout, which fell from 66% in 2019 to 58.6% this year. “How do they bring these voters that they’ve lost … in the next two years before the next local government election?” she said. “That’s a dilemma for them, because going with a DA-IFP coalition might not do that … But, equally, going the MK-EFF route is then siding yourself with people who are against the constitution.”

Once the ANC has built a coalition, it will then need to deal with the deeper question of reforming itself, said Judith February, a columnist with the Daily Maverick newspaper. “You have people who depend on politics for their livelihood and the corruption is so deep,” she said. “But at the same time, one is facing the loss of power. That focuses the mind in a way that nothing else will.”

Source: theguardian.com