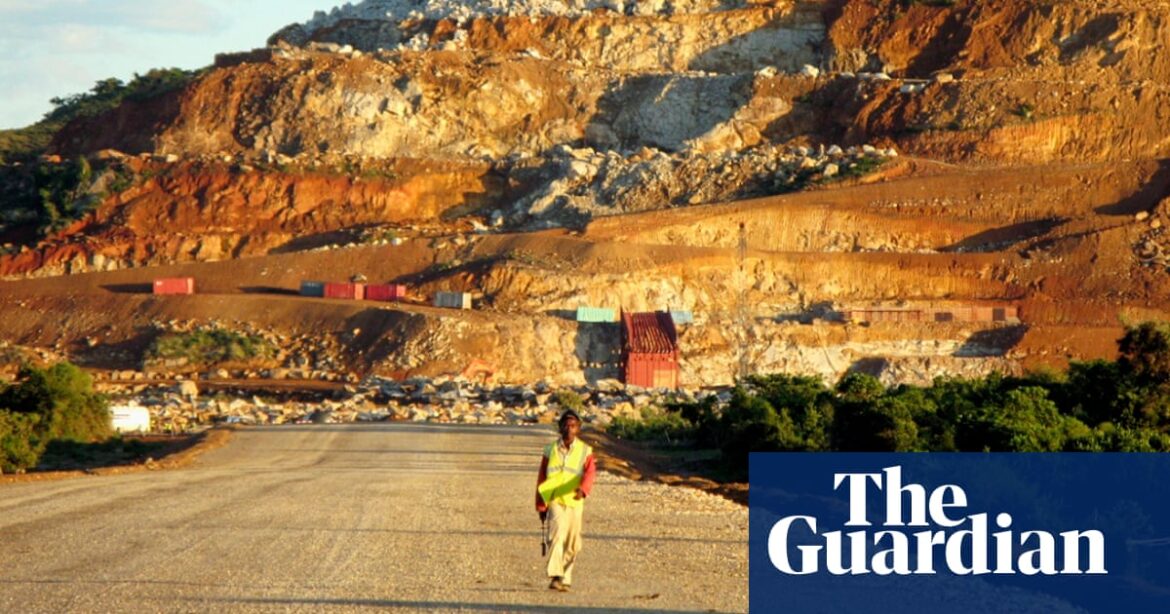

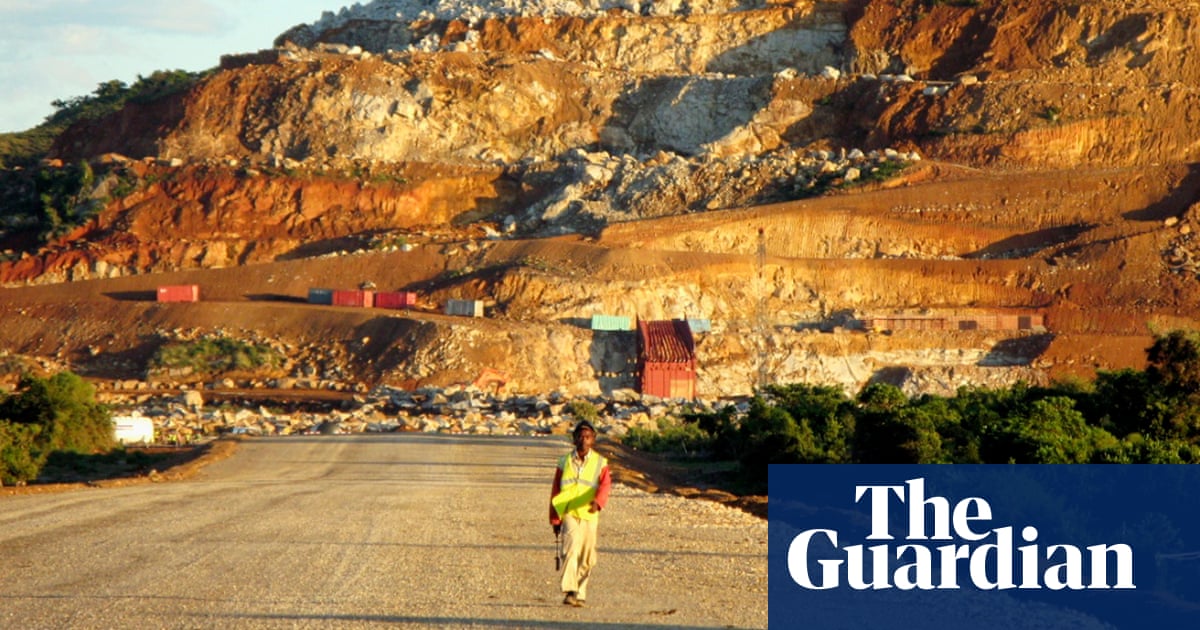

Rio Tinto is facing a likely lawsuit in an English court brought by the UK-based law firm Leigh Day on behalf of people living in villages near a mine in Madagascar.

In a letter of claim, a document that is an early step in a lawsuit, the villagers accuse Rio Tinto of contaminating the waterways and lakes that they use for domestic purposes with elevated and harmful levels of uranium and lead, which pose a serious risk to human health.

The mine, operated by Rio Tinto subsidiary QIT Madagascar Minerals (QMM), extracts ilmenite, a major source of titanium dioxide, which is mainly used as a white pigment in products such as paints, plastics and paper. It also produces monazite, a mineral that contains highly-sought-after rare-earth elements used to produce the magnets in electric vehicles and wind turbines.

Leigh Day commissioned testing of people’s blood lead levels in the area around the mine as part of its research. According to the claim, which was sent on Tuesday, the testing shows that 58 people living around the mine have elevated levels of lead, and the majority of cases exceed the threshold at which the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends clinical and environmental interventions, 5 micrograms per decilitre. The claim alleges that the most likely cause of the elevated levels is a result of QMM’s mine processes.

“Whilst Rio Tinto extracts large profits from its mining operations in Madagascar, our clients’ case is that they and other local families are being forced to consume water which is contaminated with harmful heavy metals. In bringing this case, our clients are seeking accountability and justice for the damage that has been caused to their local environment and their health,” Paul Dowling, Leigh Day’s lead partner on the case, said.

While a relatively small sample, Leigh Day’s blood lead level testing results are a significant development that may for the first time quantify the detrimental health impact their clients allege are posed by QMM. Both the pollution of surface water and lead poisoning are global problems, and the case will be watched closely not just by Rio Tinto shareholders but by global environmental justice advocates in other nations where villagers also accuse industrial giants of polluting their waterways.

“We have received the letter from Leigh Day,” said the Rio Tinto spokesperson, who declined to comment further on the allegations. The spokesperson pointed to a published report that states that the company’s recent water analysis had not detected metals, including uranium and lead, that had previously been identified as potential concerns.

Madagascar’s environmental regulator, the National Office for the Environment, or ONE, says it has periodically monitored QMM’s activities over the past decade and has tested the water after previous complaints about contamination. “In the face of these accusations, ONE requested several expert analyses … the results of which indicated no contamination of surface waters nor mining sites,” Hery Rajaomanana, ONE’s director of environmental integration and sustainable development, said in March.

Rio Tinto, which had net earnings of $12.4bn in 2022, has a troubled track record in Madagascar. Locals, civil society groups and media have accused the company of damaging the endangered forest, threatening rare endemic species,forcing villagers off their land without proper compensation, destroying fishers’ livelihoods and failing to honour its promises to employ local people. Communities have been protesting against the mine almost since its inception.

“QMM operates in a highly sensitive area from a water and broader environmental perspective,” wrote a Rio Tinto spokesperson, who declined to attach a name to the statements from the company. “We are committed to working to address any specific issues that community members raise, and to engaging in constructive dialogue on how we can mitigate impacts of our operations while generating tangible and sustainable benefits for our host communities.”

The 150-year-old metals and mining company has been embroiled in scandal for years. In 2020, Rio Tinto blew up two ancient Australian aboriginal sites to expand its iron ore mining in the region. In 2022, a review found that bullying, sexism and racism were rampant across the company. In March 2023, Rio Tinto agreed to pay a $15m penalty to the US Securities and Exchange Commission after accusations surfaced that in 2011 it paid $10.5m to a friend of the Guinean president to retain iron ore mining rights. The company is facing pressure from investors over water quality concerns at several of its mining sites, including in Madagascar and Mongolia.

“People were eating so well”

QMM started exploring for heavy mineral sands in Anôsy, Madagascar, along the south-eastern coast in 1986. The region is home to about 800,000 people, with more than 90% of rural residents living on less than $1.90 (£1.50) a day.

The area where the minerals were discovered is a unique ecosystem, a littoral forest occurring in the sandy substrates close to the Indian Ocean. Madagascar once had a continuous 1,600km band of littoral forest along its eastern coastline. Today, it is estimated that only a fraction of that forest remains intact. New species are being discovered there all the time, but many of them are already endangered by habitat destruction. Yet the region, with its famous lemurs and a concentrated diversity of plant species, remains one of the most important and fragile ecosystems in the world.

When Rio Tinto began exploring the area, the possible risks associated with a large-scale mineral sands project, including the potential for radioactive materials to be released into the surrounding environment, were not well known.

“People didn’t yet understand the ecological impact of the mine,” said Tahiry Ratsiambahotra, the founder of LuSud, an activist organisation that has become a thorn in the sides of the government and Rio Tinto. “So, parliament adopted the agreement.”

Before building the QMM mine, the company conducted a series of assessments to determine the potential social, environmental and economic impacts of the mine on the surrounding area. Baseline water testing from 2001 revealed that the surface water from lakes and rivers surrounding the mine was free from high levels of metals including lead and uranium.

To support its mining operations, QMM planned to construct a weir, or barrier, where Lake Ambavarano meets the mouth of the estuary that connects to the Indian Ocean to control water flows and water level heights. But the company was warned that the weir had the potential to permanently change the occasionally brackish lagoon system into freshwater, which would affect fish and fishers in the region. With support from the World Bank, it also built a port in Fort Dauphin to export raw materials to Rio Tinto’s processing plant in Canada.

Despite concerns by LuSud, the World Bank, and other bodies involved in early impact assessments of the mine, QMM received a legal licence to begin operations in 2005. The licence covered three mine sites to be mined sequentially under a 100-year lease from the Malagasy government.

The mine became operational in 2008. The barrier ended up entirely blocking inundations of salt water into Lake Ambavarano. Soon, nearly all the species of fish that thrived in the brackish conditions were gone. The extractive industry watchdog Publish What You Pay found in a March 2022 community survey that at least 27 fish species appear to have disappeared from the lakes since the start of the Rio Tinto mining operation.

“Before the weir, people were eating so well. They were happy. They were fishing,” said Olivier Randimbisoa, one of the lake fishers affected by the weir.

Randimbisoa has been fishing since he was 10 years old. Before the weir was built, he could choose whether he wanted to catch crab, shrimp, ocean fish or lake fish. He could make 100,000 ariary (about $22.40) each day from fishing. Now, he says he’s barely making a fraction of that.

Heavy sands

The QMM mine extracts ilmenite from mineral-rich sands by creating shallow, unlined, water-filled basins between five and 15 metres deep. By churning up the sands and passing them through a floating dredge, the mining process filters out the heavier sands, which contain ilmenite. The ilmenite is then extracted using electrostatic processing and shipped to Rio Tinto’s plant in Canada. Despite its small size, Madagascar was the fourth largest exporter of ilmenite in the world in 2022.

The mineral sands also contain radioactive elements, including uranium and thorium. The process of churning the sand allows these radioactive elements to dissolve in the mining water, which is then discharged as wastewater.

The Malagasy regulator requires an 80 metre buffer zone between a mining operation and any ecologically sensitive area to avoid contamination. In 2015, the government regulator approved QMM’s request to reduce this buffer zone from 80 metres to 50. But in 2017, Yvonne Orengo, the director of ALT-UK, a charity that works on issues in Madagascar, accused Rio Tinto of breaching the buffer zone based on a series of satellite images she captured using Google Earth.

Rio Tinto initially denied the breach in correspondence with ALT-UK. The company agreed to conduct an independent study and identified a private company called Ozius to carry it out. To ensure an independent review, Orengo enlisted the help of Dr Steven Emerman, a groundwater and mining expert, to conduct his own study. Using Ozius’s data as well as Google Earth images, Emerman calculated that, in addition to breaching the buffer zone, the company had encroached on to the lake bed by 117 metress, bringing the total breach to 167 metres, he said.

In early 2019, QMM announced that it would revise its plans and revert back to the 80-metre buffer zone. It later acknowledged that it had breached the original buffer zone.

The QMM mine relies on a “natural” system, usually referred to as passive water treatment, to treat its mining basin water. It releases the contaminated water into a series of “settling paddocks” to reduce the levels of floating particles, one indicator of water quality. When the water in the paddocks gets too high, the mine offloads the water into naturally occurring wetlands that connect to a nearby river. The idea is that the process of moving through the settling paddocks and wetlands would rid the mining basin water of its more harmful elements and allow safe water to flow into the surrounding environment.

One issue with passive water treatment systems is that they can remove contaminants, like lead and uranium, from process water and store them in the wetland sediment. A later change in wetland water chemistry, such as an increase in acidity, could remobilise those heavy metals back into dissolved form in the water column. “This is why passive water treatment systems are sometimes referred to as ‘chemical timebombs’,” said Emerman.

Rio Tinto refers to its tailings dam as a berm, or an artificial embankment, and its tailings as process water. There have been reports of berm failures at QMM since mining began, resulting in large releases of harmful mine waste. The first two were made in 2010 and 2018, and dead fish appeared in the lakes after the 2018 overflow.

In August 2020, QMM stopped regularly discharging its process water into the surrounding wetlands. The following year, Rio Tinto released a report that concluded its “natural” filtration system was not working as expected and excess levels of aluminium and cadmium were being released into the water around the mine.

Two additional berm failures occurred in early 2022, after a series of cyclones and other severe weather events battered the region. Dead fish had started appearing in the lakes again, which is what Randimbisoa, the fisher, witnessed. In response, the authorities banned fishing, which led to widespread protests from communities living around the mine.

Following the 2022 dead fish incident, QMM and the Malagasy environmental regulator analysed a series of water samples. The company says the analysis revealed no significant change to water quality in the surrounding water bodies and no link between the mine’s activities and the dead fish, but despite requests from civil society actors and the Intercept, the report has not been made available to the public.

In April 2022, ALT-UK commissioned Dr Stella Swanson, a Canada-based aquatic ecologist and radioactivity specialist, to analyse the potential causes of the fish deaths. She concluded that “the combination of acidic water and elevated aluminium in the water released from the QMM site is the most probable connection between the water releases and the fish kills observed after those releases.”

Rio Tinto and QMM dispute Swanson’s assessment, but Earl Hatley, the co-founder of the non-profit Lead Agency Inc, backs it up. A similar combination of metals and low pH in water have caused fish deaths near many other mining sites, Hatley said, including at the Tar Creek Superfund site in Oklahoma, where former lead and zinc mines caused environmental devastation, and poisoned fish and people living around the mining sites.

Blood and water

Clean water has long been a problem around the QMM mine, and in recent years, it has become the main one. About 15,000 people draw their drinking water from the lakes and waterways around the mine.

After Orengo discovered the buffer zone breach in 2017, ALT-UK asked Swanson to conduct a radioactivity study to determine the presence of radioactive material in the surrounding waterways. The study found that uranium – in concentrations up to 50 times the WHO drinking water quality guidelines for chemical toxicity – was detectable in samples from all QMM’s river water monitoring stations.

In a response, QMM denied having any impact on the high levels of uranium in the water and claimed that the elevated levels were a naturally occurring result of local geological conditions. “This is not a QMM-related impact and is an aspect of the water used by local communities before the commencement of construction or operations at QMM,” the company argued.

Emerman, the mining expert who studied the breach, conducted his own analysis using data from Rio Tinto and samples collected by local residents. He reported that the maximum downstream lead and uranium concentrations were 40 and 52 times higher, respectively, than the WHO recommended standards for drinking water. Emerman also found that lead levels were 4.9 times higher downstream of the mine and uranium levels were 24 times higher downstream. According to Emerman, these results, and their contrast with the 2001 baseline study, point to QMM as the source of contamination.

Late last year, Rio Tinto released its QMM water report 2021–2023, which included new water sampling data as well as additional information about the company’s developing water management practices. The report showed that all parameters were below the analytical limits of detection upstream and downstream of the mine’s release point during the reporting period. Emerman independently assessed the report and concluded that the new data confirmed “the detrimental impact of the QMM mine on regional water quality”, and that it failed to alter his earlier conclusions.

There were no blood lead levels testing results publicly available for the population living around the QMM mine until now. In its new claim, Leigh Day states that blood lead level testing on 58 people living around the mine, among them children, shows elevated levels of lead. Scientific studies have found that children with blood lead levels above the WHO’s threshold of 5 micrograms per decilitre are likely to suffer at least some amount of mental impairment as a result.

An expert clinical toxicologist working with Leigh Day has recommended periodic blood lead testing for all 58 of the clients who were tested. For at-risk groups such as children, women of child-bearing age, and those with a blood lead level above the WHO reference level, the expert has recommended additional interventions including clinical monitoring, more frequent blood lead testing, nutritional supplements and additional antenatal care, where appropriate. One client with particularly high blood lead levels has been advised to undergo chelation therapy, which helps remove pollutants from the bloodstream.

“Rio Tinto continues to make bold public commitments about safeguarding vital water sources and respecting the rights of those affected by its operations wherever in the world they may be,” said Dowling, of Leigh Day. “We trust the company will now stand behind those commitments and engage constructively with our clients’ claims at an early stage to ensure the communities no longer have to rely on polluted water and get the medical attention they need.”

Georges Marolahy Razafidrafara, a Mandramondramotra resident, used to work for the mine. Today, he worries about the water quality, especially because he has a daughter who is still just a toddler. “QMM always says: ‘Yeah, we take the water samples to analyse in the lab’ but we never get the results,” he said. “They always come back and say it’s drinkable, but they truck water into the mine [for their employees].”

The way Razafidrafara sees it, the local population were promised prosperity. Instead, they got poison.

-

This story was published in partnership with The Intercept. The reporting for this investigation was supported by a grant from Journalists for Transparency, an initiative of Transparency International.

Source: theguardian.com