F

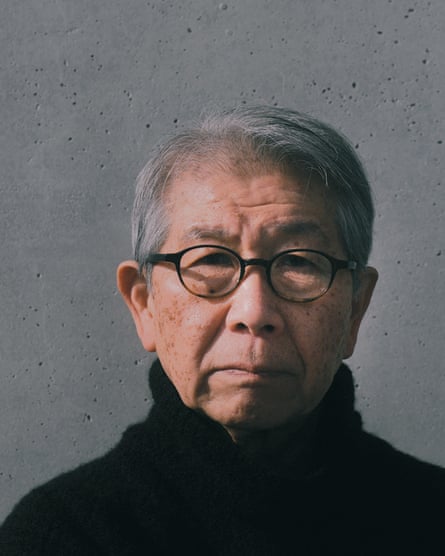

From public housing units linked by raised walkways and communal terraces, to modern university structures with transparent designs to encourage collaboration between departments, Riken Yamamoto’s architecture centers around visual impact and visibility. At 78 years old, the Japanese architect has recently been selected as the 2024 awardee of the prestigious Pritzker prize in the field of architecture.

Display the image in full screen

It’s a surprising choice. Yamamoto has never been part of the fashionable avant garde, of the “starchitect” kind that the Pritzker has often honoured in the past. Nor is he from an overlooked or undervalued region, as the prize has looked to highlight in some recent years. Instead, during a career spanning the last five decades, he has produced a consistent body of work in a neutral, modernist style, creating cubic, gridded forms in steel, concrete and glass, which might be hard to get excited about at first glance.

Upon further examination, it becomes evident that Yamamoto’s buildings display a high level of intricacy and refinement in their multi-layered and well-structured design, with a strong emphasis on promoting social interaction. Each structure is carefully crafted to cultivate a sense of community, facilitate collective experiences, and encourage mutual support. As stated by the Pritzker prize jury, Yamamoto’s architecture serves as both a backdrop and focal point for daily life, blurring the lines between public and private spaces, and creating numerous opportunities for organic gatherings.

The fire station in Hiroshima, which was constructed in 2000, is designed as a seven-story box with glass louvres covering all sides. This allows the public to have a direct view of the activities taking place inside. The rooms are arranged around a central atrium where the firefighters train, and the lobby allows visitors to access a terrace on the fourth floor, where they can observe the different work areas. This design reflects Yamamoto’s belief that a fire station plays a crucial role in shaping the local community and that the courageous civil servants should be honored and appreciated in plain sight. Similarly, his Fussa City Hall, built in 2008, is also welcoming to the public with its red tiled walls that blend seamlessly into the ground and create a gentle slope where visitors can lean against the curving walls.

Reworded: The Koshigaya campus of Saitama Prefectural University was established in 1999 and serves as a visual representation of collaboration among different departments. With a focus on nursing and health sciences, the nine buildings are linked by terraces that transform into walkways. Unique glass structures provide glimpses of neighboring classrooms and buildings, promoting interdisciplinary education. “The layout of this campus resembles a miniature city,” explained Yamamoto, “where observation is encouraged.”

The Pritzker jury’s chairman, Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, commended Yamamoto for his skill in designing welcoming and communal spaces. Aravena stated, “In the future, cities will greatly benefit from architecture that fosters connections and encourages interaction among people. Yamamoto’s contributions go beyond the initial task and effectively facilitate community building. He is a reassuring architect, bringing a sense of dignity to everyday life, and elevating the ordinary to extraordinary. His calm approach leads to magnificent results.”

Yamamoto was born in Beijing in 1945 and spent his formative years in a house that greatly influenced his understanding of space and the connection between public and private spaces. The house was designed after a traditional Japanese machiya, with his mother’s pharmacy in the front and their living quarters in the back. Yamamoto reflects, “One side of the threshold was for my family, and the other for the community. I sat in between.” This idea has been a consistent theme throughout his career, as he is constantly aware of the distinctions between public and private and the balance between individual and collective.

Yamamoto earned his undergraduate degree from Nihon University in 1967 and his graduate degree from Tokyo University of the Arts in 1971. Upon graduation, he embarked on a series of trips with his teacher, Hiroshi Hara, driving through various parts of Europe and South America for extended periods of time. He then ventured to Iraq, India, and Nepal, where he observed and documented societal interactions and the boundaries between public and private spaces.

In 1973, he established his own architectural firm, Yamamoto & Field Shop, specializing in private residential projects. One of his early clients, Mr. Yamakawa, had a straightforward request for a villa with a large terrace that would serve as an outdoor living space for summer activities. Yamamoto recalls, “We designed a house that essentially felt like a terrace.” The design features a simple pitched roof covering a group of minimalist, white, box-like structures, framing a large open deck. This concept was carried over to the Ishii House, constructed in Kawasaki in 1978 for two artists. The house consists of a single pavilion-like room that seamlessly extends into an outdoor area, serving as a platform for performances. The living quarters are located underground.

Similar to his childhood residence, Yamamoto’s initial project for social housing was constructed in Kumamoto in 1991, inspired by the way traditional machiya homes encouraged a sense of cooperation among residents. The development consists of 110 units surrounding a central square lined with trees, accessible only by passing through one of the homes. This design promotes a communal atmosphere while respecting the privacy of individual families. In keeping with his beliefs, Yamamoto’s personal residence, built in 1986, serves as a symbol of positive relationships with neighbors. It is part of a multi-functional building, with retail spaces on the lower level, featuring a series of rooftop gardens and terraces where neighbors can come together to relax or garden.

Display the picture in fullscreen mode.

Yamamoto’s views on Japanese housing have been consistently harsh. In a 2012 statement, he lamented the idea that uniform housing would lead to uniform families and a uniform workforce. He argued that the Japanese government’s approach of providing one home per family has ultimately failed.

In that same year, Yamamoto launched hisGangnam endeavor in South Korea as a means of promoting versatile housing. The project was inspired by his concept of a “Local Community Area”, aimed at fostering cooperation and assistance among residents. According to Yamamoto, housing should no longer just serve as a living space for families and child-rearing, but rather can develop a new system by involving the local community in various activities. This approach would also benefit individuals living alone by preventing feelings of isolation.

The individual used comparable societal concepts in creating primary schools, college campuses, and art museums. In his 2006 Yokosuka Museum of Art, there are circular openings that allow for views of the surroundings and other galleries, ensuring that visitors remain aware of the museum’s activities. Similarly, his 2012 Tianjin library consists of ten intersecting levels with staggered reading platforms and walls adorned with books.

Yamamoto expresses his modest demeanor through his foreword in his 2012 monograph. He openly admits, “I am not skilled in design.” Yet, he takes careful notice of his surroundings, including the environment, local community, and current societal circumstances. This book is an account of his attentiveness, and he encourages those who do not have confidence in their design abilities to read it.

Source: theguardian.com