The area of the Amazon where Brazil, Colombia, and Peru meet – referred to as Tres Fronteras (triple frontier) – brims with wildlife and natural resources. It is also a hotbed of illicit activity. Criminal groups are clearing the forest to plant coca and erect laboratories to turn the crop into cocaine. In the process of making coca paste, these labs discharge chemical waste – including acetone, gasoline and sulphuric acid – into rivers and soil.

Increasingly, these outfits are branching into illegal logging, gold dredging and fishing, in part because these activities allow them to launder money made from drug trafficking. These activities compound the environmental harm the groups are inflicting.

The consequences of this criminal activity reverberate far beyond the Tres Fronteras. The Amazon is a pre-eminent carbon sink, absorbing substantial atmospheric carbon dioxide. Through its central role in the hydrological cycle, the Amazon also profoundly influences global weather and precipitation patterns. Its unparalleled biodiversity is essential for maintaining ecological balance. In sum, the planet’s environmental health hinges in part on what is happening in this corner of the world.

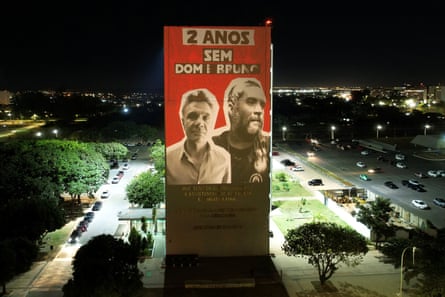

The assassination of Dom Phillips, a Brazil-based British journalist and Guardian freelance contributor, and his local guide and Indigenous rights defender, Bruno Pereira, brought the region’s high level of violence to international attention. Well before these killings, however, criminality had been on the rise across the region.

The Tres Fronteras has some of the highest rates of violence in Latin America, which itself is the region with the world’s highest homicide rate. Communities in the area have faced death and displacement threats, while criminal groups have stepped up their recruitment of minors.

Overlooking the vast Amazon River from the high riverbank in front of his community, a scarred Indigenous man in his late 30s laments that he had joined an illicit group at the age of 13, eventually becoming a hitman. “Every night when I close my eyes, I see the faces of those I’ve murdered, the bodies I have dismembered,” he says, recalling his past as a contract killer for drug traffickers.

At particular risk from booming crime are the uncontacted Indigenous tribes. These communities live deep within the jungle, having successfully evaded interaction with western civilisation for centuries, such as the Yuri Passé tribe in Colombia.

The unbroken perimeter of their territory, which is protected by law, is on the verge of being breached by encroaching goldminers, drug traffickers and regional Colombian guerrilla groups, threatening not only their culture but also their existence. It is not just violence that can prove lethal, but the fact that outsiders expose these tribes to diseases they lack immunity to.

State officials are fighting a losing battle as they struggle to cooperate across borders. Each country’s forces cannot pursue and arrest criminals outside their jurisdiction, making it possible for criminals to make quick escapes across borders when they are in danger of being apprehended.

Police and other security forces acknowledge the need to coordinate better but admit they fail to efficiently share information with their colleagues across the border due to trust issues.

“What happens there affects us here,” says a Colombian law enforcement official. But thus far, transnational cooperation has been scant. In addition, criminal outfits outgun and outman law enforcement in the region. “We are a bit afraid,” a state official in Peru tells me. “They can kill us.”

A lack of resources severely hampers the security forces’ ability to combat crime. In Islandia, Peru, a town isolated like an island, police are unable to pursue drug and timber traffickers because their two boats are inoperable. Officers pooled their money to buy a wifi router but still have no working internet service and lack a functional printer for official documents.

So, what should be done? The growth of crime in the Amazon reflects the struggles that states across Latin America face in providing honest and effective law enforcement, particularly in their borderlands.

However, local people in the Tres Fronteras area know how to protect their lands. Indigenous groups have proved to have lower deforestation rates in areas where they have collective land titles. Indigenous peoples have also organised independent and unarmed guards to patrol their ancestral lands and detect violent invaders such as illegal fishers, goldminers or drug traffickers.

These initiatives could, in theory, operate as an early warning system for government officials seeking to stave off criminal groups’ illicit incursions, and state governments should capitalise on the opportunity these grassroots efforts offer to protect the rainforest.

Paramount for moving ahead is political will. During a 2023 summit, eight Amazon countries agreed to increase security cooperation. Hopes are high for renewed momentum in political dialogue and cooperation during this year’s Biodiversity Cop16, which Colombia will host in October, and at Climate Cop30, which Brazil will organise in the Amazon city of Belém do Pará in November 2025.

Crucially, sustainable security strategies should prioritise Amazon populations, sanctioning those who orchestrate environmental crime while supporting lawful livelihoods and with more robust collaboration with Indigenous communities to curb criminal expansion.

Alternatives to crime are essential for youths to avoid being swallowed up by criminal activities and disconnected from their communities, as recognised by the former assassin who has been away from the gang’s influence for several years now. “I’ve learned to be a person again,” he says.

-

Bram Ebus is a researcher and journalist based in Bogotá. He contributed to the International Crisis Group’s recent briefing, A Three Border Problem: Holding Back the Amazon’s Criminal Frontiers.

Source: theguardian.com