Starmer was already committed to raising defence spending to 2.5% of GDP at some point, and an increase by the time of the next election, although not announced, was already priced in. Hitting 2.5% by 2027 was not nailed-on, but it is probably in the mid-range of what was expectated. It is enough of a surprise to cause a jolt (because ministers had been swearing blind until recently that no announcement was coming this week). But it is not a transformational uplift, and it won’t silence calls for defence spending go go higher. We heard quite a few of them in the Commons during the statement (eg, see 2.30pm).

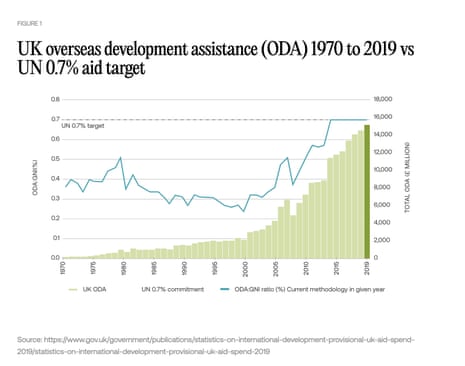

Many MPs, though, were shocked to see that axe taken to the aid budget quite so drastically. By taking aid spending back down to 0.3% of GDP (or GNI, gross national income, to be more accurate – people tend to say GDP instead because it means something similar, and the acronym is better understood) Starmer will be taking British development policy back to the 1990s. The blue line in this chart (from a report from the Tony Blair Institute) illustrates the trend.

In doing this, Starmer is undoing one of the most signifcant achievements of the New Labour government. Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were both strongly committed to raising aid spending to the 0.7% UN target, and David Cameron pushed ahead with that, despite leading a party that historically had felt more indifferent about overseas aid, partly because he was using that as a way of showing the Tories had modernised. The chart is from a report published in January 2021, when the 0.7% target had been hit. That’s why the blue line is flat from 2013. Blair’s achievement looked secure. But a few months after the report was out, Boris Johnson slashed aid spending to 0.5%, and now it is going down even more. In his Commons statement Starmer said “we will do everything we can to return to a world where that is not the case”, implying that the aid spending cut was only temporary. But you would have to be brave to put money on it getting back towards 0.7% any time in the foreseeable future.

Starmer would be raising defence spending at some point even if he were meeting President Harris in the White House on Thursday, not President Trump. But this announcement will help soothe relations with Trump. Starmer can say he has listened to his host on defence spending. And he could even claim that, in cutting aid spending, he is also following the lead of the Trump administration (which has closed down its aid department) – although he is unlikely to spell it out that bluntly, given how Labour MPs might react.

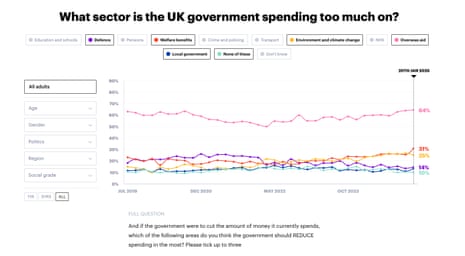

But there are Trump-style politics in this. In his speech at the Munich Security Conference, JD Vance, Trump’s vice-president, said that there was no hope for European democracy if politicians tell voters “their thoughts and concerns, their aspirations, their pleas for relief are invalid or unworthy of even being considered”. Vance was referring to immigration policy, but he could have been talking about aid spending too, because polls repeatedly show that people think it is too high. Rightwing voters are more likely to think this than leftwing voters, but even Labour and Lib Dem supporters think in these terms. Many Guardian readers will hate the idea of aid being cut, and the consequences will be real and drastic. (See 3.17pm.) But Starmer may find this the most popular policy he has announced to date.

Keir Starmer might appoint David Miliband, the former Labour foreign secretary, as his ambassador to Washington. Peter Mandelson got the job instead, and Miliband stayed in his post as CEO of the International Rescue Committee, a major, US-based aid charity.

And in that capacity he has issued a statement today criticising Starmer for cutting the UK’s aid budget. He says:

The UK government’s decision to cut aid by 6 billion in order to fund defence spending is a blow to Britain’s proud reputation as a global humanitarian and development leader. Today, an unprecedented 300 million people are in humanitarian need around the world. The global consequences of this decision will be far reaching and devastating for people who need more help not less.

We recognise the complex challenges facing the UK government in today’s unstable world. The UK aid budget is famed for its value for money, innovation and impact for those in the greatest need around the world. We don’t know where the aid cuts will fall, but we do know that current investments are meeting desperate needs. The danger is that without humanitarian help more people will flee their homes to seek security and global health will be severely compromised.

the text of his statement suggests, he is doing it because he thinks it is inevitable and right.

Starmer was already committed to raising defence spending to 2.5% of GDP at some point, and an increase by the time of the next election, although not announced, was already priced in. Hitting 2.5% by 2027 was not nailed-on, but it is probably in the mid-range of what was expectated. It is enough of a surprise to cause a jolt (because ministers had been swearing blind until recently that no announcement was coming this week). But it is not a transformational uplift, and it won’t silence calls for defence spending go go higher. We heard quite a few of them in the Commons during the statement (eg, see 2.30pm).

Many MPs, though, were shocked to see that axe taken to the aid budget quite so drastically. By taking aid spending back down to 0.3% of GDP (or GNI, gross national income, to be more accurate – people tend to say GDP instead because it means something similar, and the acronym is better understood) Starmer will be taking British development policy back to the 1990s. The blue line in this chart (from a report from the Tony Blair Institute) illustrates the trend.

In doing this, Starmer is undoing one of the most signifcant achievements of the New Labour government. Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were both strongly committed to raising aid spending to the 0.7% UN target, and David Cameron pushed ahead with that, despite leading a party that historically had felt more indifferent about overseas aid, partly because he was using that as a way of showing the Tories had modernised. The chart is from a report published in January 2021, when the 0.7% target had been hit. That’s why the blue line is flat from 2013. Blair’s achievement looked secure. But a few months after the report was out, Boris Johnson slashed aid spending to 0.5%, and now it is going down even more. In his Commons statement Starmer said “we will do everything we can to return to a world where that is not the case”, implying that the aid spending cut was only temporary. But you would have to be brave to put money on it getting back towards 0.7% any time in the foreseeable future.

Starmer would be raising defence spending at some point even if he were meeting President Harris in the White House on Thursday, not President Trump. But this announcement will help soothe relations with Trump. Starmer can say he has listened to his host on defence spending. And he could even claim that, in cutting aid spending, he is also following the lead of the Trump administration (which has closed down its aid department) – although he is unlikely to spell it out that bluntly, given how Labour MPs might react.

But there are Trump-style politics in this. In his speech at the Munich Security Conference, JD Vance, Trump’s vice-president, said that there was no hope for European democracy if politicians tell voters “their thoughts and concerns, their aspirations, their pleas for relief are invalid or unworthy of even being considered”. Vance was referring to immigration policy, but he could have been talking about aid spending too, because polls repeatedly show that people think it is too high. Rightwing voters are more likely to think this than leftwing voters, but even Labour and Lib Dem supporters think in these terms. Many Guardian readers will hate the idea of aid being cut, and the consequences will be real and drastic. (See 3.17pm.) But Starmer may find this the most popular policy he has announced to date.

Keir Starmer should reconsider the aid cuts. In a statement she says:

I urge the prime minister to rethink today’s announcement. Cutting the aid budget to fund defence spending is a false economy that will only make the world less safe.

Conflict is often an outcome of desperation, climate and insecurity; our finances should be spent on preventing this, not the deadly consequences.

In 2023, Ukraine received £250m in UK aid, more than any other country. We simply cannot afford to undermine this investment by putting more into a war chest.

Keir Starmer wants to get defence spending to 3% of GDP, cuts to overseas aid won’t be enough. It has issued this statement from Ben Zaranko, an IFS associate director.

If the UK needs to spend more on defence on a structural and permanent basis, that is not something that can be sustainably borrowed for. The prime minister has recognised this, and has signalled that higher defence spending will be offset, at least in the short term, by lower spending on overseas aid. If defence spending needs to go higher than 2.5% of GDP, cuts to aid won’t be enough. Getting towards 3% of GDP will eventually mean more tough choices and sacrifices elsewhere – whether higher taxes, or cuts to other bits of government. The world has changed, and one question is whether the government’s pre-existing promises on tax and spend might need to change as well.

But, in his statement, Zaranko also says one of the figures quoted by the PM in his statement (see 1.45pm) is misleading. Zaranko explains:

As a minor note to what is a major announcement, the prime minister followed in the steps of the last government by announcing a misleadingly large figure for the “extra” defence spending this announcement entails. An extra 0.2% of GDP is around £6bn, and this is the size of the cut to the aid budget. Yet he trumpeted a £13bn increase in defence spending. It’s hard to be certain without more detail from the Treasury, but this figure only seems to make sense if one thinks the defence budget would otherwise have been frozen in cash terms. This is of course dwarfed by the significance of today’s announcement but is frustrating none the less.

Back in the Commons, Jeremy Corbyn, Starmer’s predecessor as Labour leader, says this statement will have a bad impact on the poorest people in the world. He asks what impact it will have on the poorest people in the UK, suggesting that higher defence spending will mean more welfare cuts.

Starmer replies:

It is the first duty of government to keep our country safe and secure. It’s a duty I take extremely importantly and the poorest people in this country would be the first to suffer if the security and safety of our country was put in peril.

on social media.

Labour copy more @reformparty_uk policies

We said increase defence spend to 3% in 6 yrs

We said slash foreign aid budget

Starmer agrees with Reform

We are the real opposition

on social media.

This is quite a grave moment in the Commons, people will understand an increase in defence spending is necessary but it also feels like another step closer to conflict.

Starmer, presumably, would argue that higher defence spending is needed to avoid conflict. (See 1.41pm.)

In the Commons Starmer has just restated this point. In response to a question from the SNP’s Dave Doogan, who said that women and children would suffer most as a result of the aid cuts, and that some of them might die as a result, Starmer says:

Wherever there are war and conflict, it is the poor and the poorest who are hit hardest. There is no easy way through this, but we have to ensure that we win peace through strength, because anything other than peace will hit the very people [Doogan’s] identified harder than anybody else on the planet.

on social media.

People will understand an increase in defence spending to pay for peacekeeping in Ukraine but to cut spending on tackling famine & poverty in the poorest areas of the world will cost lives. The Chancellor’s fiscal rules are undermining this government’s moral standing & purpose.

Bernard Jenkin (Con) says he does not think 2.5% or even 3% of GDP would be enough for defence spending. He says he is saying that, not as a criticism, but because he thinks the nation must get used to the idea it will have to spend more.

Starmer acknowledges that Jenkin has for many years been an advocate for higher defence spending.

Source: theguardian.com