A new pilot program is urging doctors at Great Ormond Street to take into account the air pollution levels at their patients’ residences when determining the factors behind their illnesses.

Data showing the average annual air pollution rates at patients’ postcodes has been embedded in patients’ electronic files, so that clinicians can help families understand whether their child has been exposed to elevated risk.

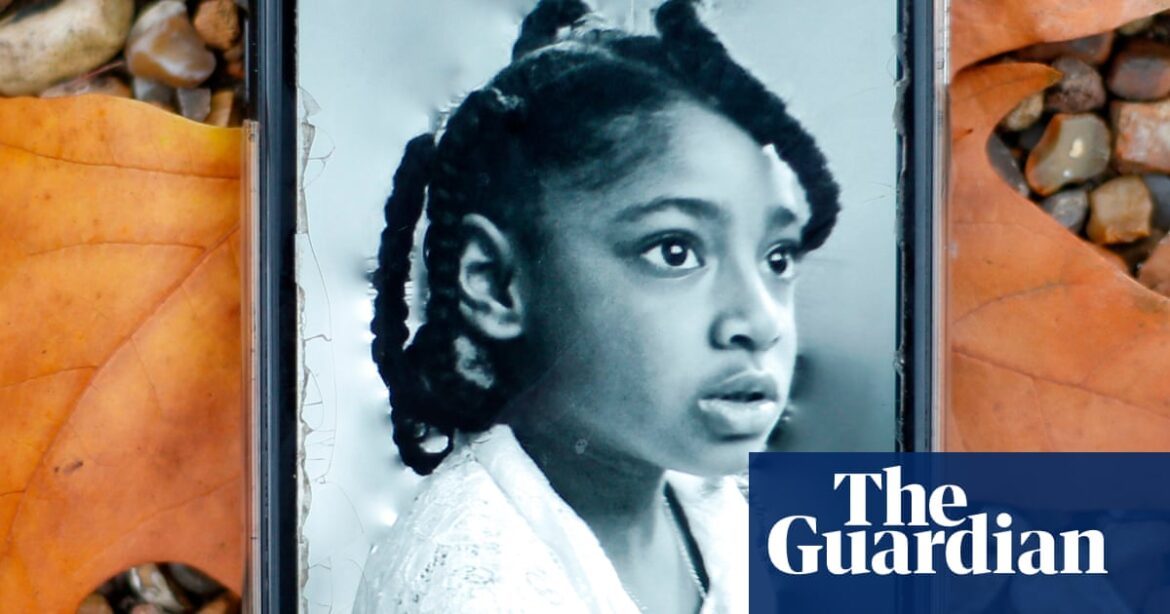

In light of the criticism from the coroner during the investigation of Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah’s death from asthma 10 years ago, the initiative was launched. In 2020, Ella became the first person in the UK to have air pollution listed as a cause of death on her death certificate.

The coroner, Philip Barlow, observed that Ella’s mother, Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, was not informed about the health hazards of air pollution and its ability to worsen asthma. In his report aimed at preventing future deaths, Barlow cautioned that the negative impact of air pollution on health was not being adequately communicated to patients and their caregivers by healthcare professionals. He urged medical personnel to take more action in educating families about the risks associated with air pollution.

If Ella’s mother had known that her daughter was being harmed by the air she was breathing, she would have relocated immediately.

Mark Hayden, a member of the intensive care unit staff, along with colleagues Nicola Wilson and Johanna Andersson, came up with the idea for the Great Ormond Street hospital initiative. According to Hayden, the hospital had a lack of understanding about air pollution and its impact.

Data added to patients’ electronic records provides information on fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide, and indicates whether they exceed World Health Organization safe levels. The information will encourage clinicians to think about whether air pollution is a factor in the patient’s illness. The pilot model has recently also been adopted by the Evelina children’s hospital, Guy’s and St Thomas’ and King’s College hospitals in London, so that air pollution is now visible on more than 2.5 million patients’ files.

Last year, Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer for England, emphasized the need for doctors to educate patients on the dangers of air pollution in a report on its impact on health. He also highlighted the importance of training healthcare professionals in guiding patients on ways to reduce exposure to air pollution. The coroner of Ella also urged for improved education on the effects of air pollution for medical staff.

At Great Ormond Street, the air pollution data will only appear if the levels in the child’s area exceed the safe limit guidelines set by the WHO for 2021. Knowing that older doctors may not have received training on the potential health risks of air pollution, Hayden has included links to informational pages in the patient files of those who have been exposed to high levels of pollution. These pages reference WHO guidelines stating that air pollution is the main threat to human health caused by the environment and is responsible for 7 million deaths globally each year. The link that appears mentions that 40% of premature births worldwide (6 million) can be attributed to PM2.5 pollution annually.

Another choice is available to compose a letter for parents outlining actions they can implement to reduce their child’s exposure to air pollution. A sample letter is also included, which parents can send to their MP to bring attention to the fact that doctors have warned them of the detrimental effects of air pollution on their child’s health.

The Royal College of Physicians addressed the issue in their official response to Ella’s inquest, recognizing that healthcare professionals often avoided discussing it. They stated, “Many patients and their families may not have the ability to make necessary changes, such as their living, work, and recreation environment. As a result, doctors and other clinicians may be unsure of the potential benefits of having this conversation.”

Hayden acknowledged that there is a longstanding discomfort among staff when discussing the health hazards associated with air pollution. He pointed out that addressing air quality is more challenging compared to treating an infection, as it cannot be remedied with antibiotics alone.

The respiratory pediatrician, Andrew Turnbull, mentioned that staff members have started discussing outdoor air pollution with patients who have severe asthma. These conversations are in addition to discussions about tobacco and e-cigarette vapors, exposure to mold and dampness, and allergies to dust and pets.

“We’ve had a long understanding of the robust links between poor air quality and adverse outcomes, but getting data at this level is new,” he said. Given that most families do not have the option to move to less polluted areas, conversations are limited to strategies to reduce an individual’s air pollution exposure, perhaps around modifying a patient’s route to school.

Since many respiratory illnesses have multiple, intricate causes, it is difficult to connect one specific cause to an individual’s disease. However, incorporating data on air pollution could offer significant research opportunities, allowing experts to better comprehend the connection between harmful pollution and a patient’s individual outcomes, according to Turnbull.

Hayden is hopeful that the initiative will have a broader reach, specifically within GP practices. He acknowledges that there are ethical concerns, as it would be unfair to burden families who are unable to address the issue. However, the goal is to provide clinicians with the necessary tools to have a meaningful discussion with families, who can then utilize the information to safeguard their children from potential harm.

Source: theguardian.com