A Chinese prisoner’s ID card was discovered in the lining of a Regatta coat, sparking concerns about the use of prison labor in the production of the British brand’s clothing.

A woman from Derbyshire purchased a waterproof coat for women during the Black Friday sale online. Upon its arrival on November 22nd, she noticed a rectangular object in the right sleeve that hindered her elbow’s movement.

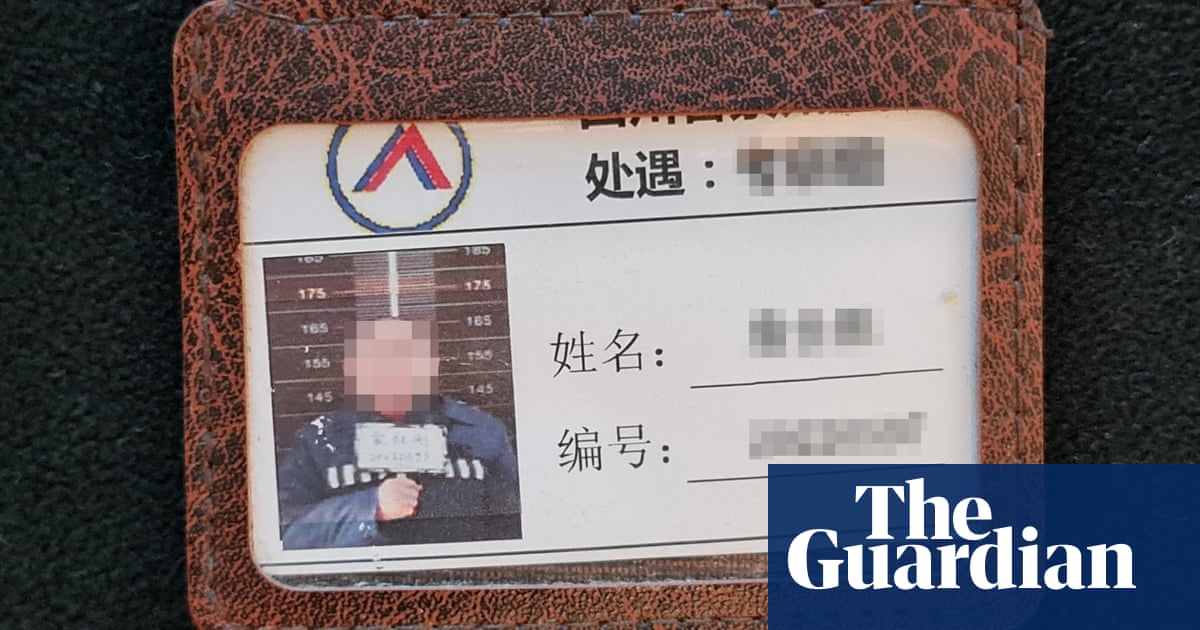

Upon slicing into the coat to extract the object, she came across what appeared to be a prison ID card. The card featured a mugshot of a man dressed in a prisoner’s uniform, standing in front of a measurement chart, and indicated that he was incarcerated in a Chinese prison.

The woman, who prefers to remain anonymous, expressed her surprise at the actions of [Regatta], a well-known UK brand that is typically associated with high-quality brands like Next and M&S. She mentioned that she would often dress her children in their clothing, but recent events have left her feeling unsettled and uneasy.

The plastic holder with the words “Produced by the Ministry of Justice prisons bureau” embossed on it contained the card.

The customer service agent at Regatta received a photo of the ID card from the woman through the website’s chat service. The agent responded with surprise, saying it was the first time they had seen such a thing.

The woman inquired if the ID was a prison identification, to which the agent replied, “No, it’s a Chinese work ID from our factory in China. However, you are correct, it does resemble a prison ID.” The agent instructed the woman to get rid of the ID.

Although she was initially uncomfortable, the woman discarded the card and didn’t give it any further thought. However, the company sent her an email that night requesting her to send back the ID and coat. The following day, she had conversations with multiple Regatta employees over the phone.

The woman was encouraged by the company to give back her ID card. They promised to replace her original coat, which had a hole in the sleeve, and also send her an extra coat as a goodwill gesture. However, she declined the offer and instead retrieved her ID card from the trash.

The Regatta company refutes the claim that they offered a new coat in return for the ID card.

The woman expressed discomfort with the situation. She acknowledged that it may be considered legal in China, but the standards and expectations may differ in the UK. Nevertheless, it is unexpected for prisoners to be involved in clothing production.

Regatta has stated in their 2023 report on modern slavery that they do not allow forced or imprisoned labor in their supply chain. They are a part of the Ethical Trading Initiative, which has certain guidelines in place, such as not allowing forced, bonded, or involuntary prison labor. The report also mentions that 70 factories were audited during the 2022-2023 period, but it is unknown how many of these were located in China.

A representative from Regatta stated that they took a customer’s reported incident seriously and immediately launched an investigation. As a company and member of the Ethical Trading Initiative, they have strict policies to ensure ethical working conditions and do not tolerate forced or prison labor. After a thorough investigation, it was determined that the garment in question was made in a factory that complies with all regulations and multiple inspections, including a certified third-party visit, found no violations of their policies.

“We are still looking into how the object ended up being stitched into the clothing.”

The coat’s origin is listed as China, but both the Regatta website and a QR code on the coat indicate that it was also manufactured in Myanmar. The label states that it was made in July 2023.

The employment of inmates is widespread in China. According to China’s prison regulations, “Prisons follow the principles of using punishment and rehabilitation, as well as education and labor, to reform criminals and turn them into law-abiding citizens.”

The website of the prison listed on the ID card discovered in the Regatta coat states that its main focus is on manufacturing clothing and handling electronic components. Based on regional regulations, inmates in that region typically earn 1-1.5 yuan (£0.11-£0.17) per hour. For the safety of the person and the prison, The Guardian has chosen not to disclose their names.

It is unclear how the identification card ended up in the coat or if it was intentionally placed there. Handwritten messages from Chinese inmates are sometimes discovered in everyday items, like in 2019 when a note written in English was found by a six-year-old girl in a Christmas card sold at Tesco. The message stated, “We are prisoners from a foreign country being held in Shanghai Qinqpu prison in China. We are being forced to work against our will. Please assist us and inform human rights organizations.”

Last month, the French broadcaster Arte aired a documentary about a handwritten Chinese letter that was found inside a pregnancy test bought in Paris. The anonymous note said: “Dear friends, do you know that behind your peaceful life, there are Chinese prisoners,” according to the documentary.

The discovery made in the Regatta coat is atypical as it singles out a particular person, putting them at risk of consequences, and was not accompanied by a message.

According to Peter Humphrey, a former journalist who served almost two years in Shanghai Qingpu prison, if an inmate hides this item in a coat they are working on, it is to inform people outside of the country that the item was made by prison labor. Humphrey currently advocates against products made with prison labor in China, as he personally observed it during his time in Qingpu prison.

According to Sarah Brooks, the deputy regional director for China at Amnesty International, it is the responsibility of companies to ensure that their supply chains are free from any human rights violations, regardless of where they operate. She also emphasizes that the mere presence of allegations of forced or compulsory labor should serve as a warning to companies about the potential risks associated with being connected to such abuses.

Further investigation conducted by Chi Hui Lin.

Source: theguardian.com