The main merchandise outlet was predictably rammed within moments of the rain arriving at 11.01am on Wednesday, but one flight of steps below the spending frenzy, the Wimbledon Museum was a welcome diversion while waiting and hoping for the covers to be removed.

The museum’s collection of equipment, documents, artefacts and general tennis ephemera is as comprehensive as you would expect at the home of the club that gave lawn tennis to the world, and the journey through the history of both the sport and the tournament is worth half an hour of any fan’s time, rain or shine.

A poster advertising the championship in 1893, meanwhile, is a reminder that Wimbledon has always had one eye on the weather. The tournament was due to start on Monday 10 July “and the following days at 4.30”, with the rider that “the Championship Match will probably be played on July 17.”.

Admission improbable

Admission prices in 1893, incidentally, varied by the day. A shilling was enough to get you through the gates on the first three days, but the tickets shot up to two shillings and sixpence for the rest of the tournament. The Bank of England’s handy inflation calculator suggests the priciest tickets in the late Victorian era cost the equivalent of £13.46 today. The price of a punnet of strawberries in 1893, however, is sadly unrecorded.

A grounds ticket, offering access to all but Centre Court, No 1, No 2 and No 3, is £30 for the first eight days of this year’s championships, while a seat on Centre Court ranges from £90 on the first two days to £275 on finals weekend. The organisers, though, would probably argue – quite fairly – that the standard has increased just as abruptly over the past 131 years.

Coco’s cannon

You can only imagine what the earliest champions would have made of serves like the 124mph (199.5kph) bomb that Coco Gauff launched at Caroline Dolehide during their first-round match on Monday. It has already trounced the record service speed in the women’s singles at last year’s tournament – 121mph/195kph by Aryna Sabalenka – and is the fastest by a woman here since Gauff walloped one at 125mph/201kph in 2021.

That already puts her joint-third on the all-time list, and Gauff’s effort on Monday leaves you wondering what she could do if or when she really warms up. Venus Williams’s all-time record of 128mph/206kph set in 2008 is a tall order, but her sister Serena’s fastest serve – 126mph/203kph in 2004 – could be in danger.

What’s in an SSQ?

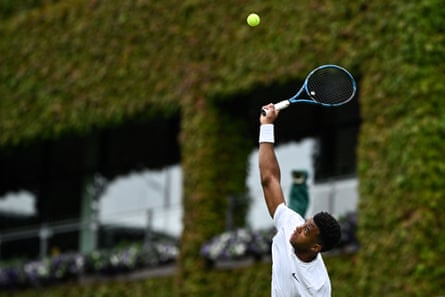

But speed, of course, is not the only thing that matters. IBM’s latest stats package analysing the first two days of the tournament suggests that – like Gauff’s lightning serve – Giovanni Mpetshi Perricard’s “serve shot quality” rating of 9.6 during his five-set win against Sebastian Korda, the No 20 seed, on Monday will take some beating over the next week and a half.

The highest SSQ – which is “calculated in real-time by analysing the speed, spin, depth and width of every shot” – at Wimbledon 2023 was 9.3, and in addition to firing down 51 aces, Mpteshi Perricard averaged 136mph/219kph on his first serve with 71% going in, and 126mph/203kph on the second. He also faced 11 break points – and saved the lot.