Two scenes from an extraordinary week. The first: Justin Rose, a gentleman in a bearpit as Augusta hollered loud and long for Rory McIlroy. The second: the British tennis player Harriet Dart, causing a stink by asking for her French opponent to apply deodorant as “she’s smelling really bad” before succumbing to a 6-0, 6-3 thrashing.

Pressure does strange things, of course. But the wildly different reactions of Rose, Dart and indeed McIlroy, whose final round became part white-knuckle ride, part pass‑the‑parcel, raises an intriguing question: when the heat is on, should sport stars let their emotions out or bottle them up to improve their performance?

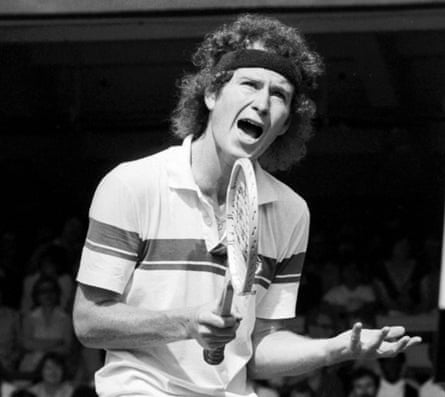

Of course it is encoded in sport’s DNA that letting off steam can sometimes be a good thing. Remember John McEnroe’s snarling soliloquy at Wimbledon, which began with him screaming “You cannot be serious” at the umpire Edward James? That came in his first-round 1981 match against Tom Gullikson – which he won, before going on to beat Bjorn Borg in the final.

McEnroe repeated the trick during the Queen’s Club final in 1984, when the Reuters correspondent noted that he “abused the umpire, a spectator and his American opponent in a three-minute shouting match in the second set before winning his fourth Stella Artois title”.

Those three minutes included calling the umpire a “moron”, telling a fan “one of me is worth 40,000 of you”, and accusing his rival Leif Shiras, who was practising his swing on the baseline while this was going on, of mocking him. “Don’t make fun of me,” McEnroe spat. “I’ve been around too long and I don’t want to take crap from you.” Having got that off his chest, he went on to win the tournament.

McEnroe is an extreme case, but we can all cite sports stars who have seemingly played better angry. Novak Djokovic, for one, uses any perceived slight as a fuel. Wayne Rooney, Duncan Ferguson and Jelena Ostapenko always appeared to play better when on the edge of losing it.

Then again, look at Roger Federer, who went from a teenage hothead, chucking rackets and crying after defeats, to being the ultimate nice guy. “I used to tell him, your bad behaviour is like an invitation to your opponent, saying: ‘Here I am, beat me,’” his mum Lynette remembers. But all that changed as he matured and worked with a psychologist.

What does the science say about all this? According to Professor Andrew Lane, who has worked with multiple Olympic and world champions, the evidence is surprisingly clear. “McEnroe was the exception,” he says. “For most sports people, if they don’t control your emotions it costs them. Letting off steam may feel natural but it disrupts performance, energises the opposition and shifts crowd dynamics.”

Lane, a sports psychologist at the University of Wolverhampton, points to recent research that looked at 77 professional volleyball players in the top two Spanish leagues and found that poor emotion regulation and impulsivity was linked to lower performance. “In particular, athletes who struggle to manage negative emotions often make rash decisions or become distracted – both performance killers.”

The study, which questioned each player about various emotions and thought processes before analysing their successes and errors in matches, had other interesting findings. Players in the second division were significantly more sensation seeking (“I quite enjoy taking risks”), for instance, and made more errors. Meanwhile female players were more likely to have what the academics called negative urgency (“When I am upset, I often act without thinking”), which was also correlated with more mistakes.

“The results show that elite female volleyball players tend to react more impulsively than men in adverse conditions, contrary to what a biological explanation might reflect,” the researchers say. They also made a number of suggestions for coaches to counteract extreme pressure – including playing down the importance of the game situation, and using timeouts and substitutions to help players to mentally reset.

after newsletter promotion

Another study found that athletes who lacked effective strategies to control their emotions experienced more anxiety during competition and were less likely to achieve their performance goals. “In other words, while venting may feel momentarily relieving, it’s not a strategy that pays off in elite sport,” Lane says.

The good news, Lane says, is that composure is not an inborn trait and can be developed. So if he were advising Dart, what would he suggest? “Athletes need to practise emotion regulation just like any other skill. It starts with learning to identify what you’re feeling in the moment – naming it. Then you can decide what’s the best response for the context: do you reframe it, ride it out, or refocus?”

One method Lane uses is to review video footage of specific moments where emotions ran high. “We turn those situations into learning points – how to think differently, how to pause instead of react. The aim is not to suppress emotion, but to manage it in ways that help performance.”

But there is another point he stresses. The best athletes – including Usain Bolt, Serena Williams at the US Open and Federer – are masters at using positive emotions to get the crowd on their side, which helps when the pressure is greatest. “While if you’re getting really angry, that crowd tends not to like you,” Lane says.

Such behaviour can cost matches, titles, and more. “These days it literally doesn’t pay to lose your temper,” Lane says, before returning to the stark contrast between Rose and Dart last week. “Graceful composure isn’t just about image – it’s a sign of psychological skill and competitive intelligence. And, crucially, it can be learned.”