During the final moments of the Five Nations match between Wales and France in March 1976 at Cardiff Arms Park, the Welsh team was defending against the French’s attack. At one point, French wing Jean-François Gourdon managed to break through and make his way down the touchline by the north stand. However, he was met with a powerful shoulder charge from Wales’s full-back, JPR Williams, which nearly sent him flying into the crowd. Williams then raised his fist in celebration and Wales ultimately won the game 19-13, securing their seventh grand slam.

Although Williams’ tackle was not within the rules, it remains a memorable moment for Welsh rugby fans. Another unforgettable image is a photo of the Bridgend No 15 covered in blood after being stepped on by an All Blacks player. Rugby in the 1970s was not for the faint of heart, and JPR’s success was not only due to his exceptional skill, but also his toughness.

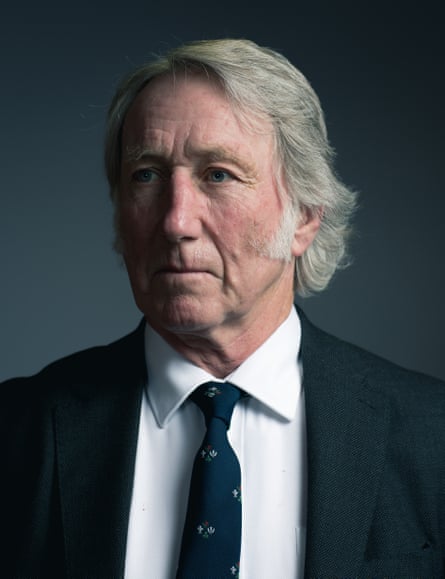

Williams, who has died aged 74 from bacterial meningitis, would forever be known as JPR, the three most evocative initials in the sport. Only France’s Serge Blanco could rival him as the greatest full-back in history. When the law-makers of the international board prevented the ball from being kicked directly into touch in 1968 it gave the opportunity for Williams and others such as Scotland’s Andy Irvine to forge a template for how a modern attacking full-back should play.

Williams’s well-known toughness comes from an unexpected place. Unlike many other elite Welsh players, he grew up in a privileged middle-class household. Williams once shared a story of how he arrived at a Wales Schoolboys’ tryout in a Rolls Royce. He explained that his upbringing motivated him to show his peers that he was strong and belonged with them.

John Peter Rhys was born in Bridgend to parents Peter and Margaret, who were both doctors. Margaret was originally from Rochdale, giving John the opportunity to potentially play for England, although this was not a topic commonly talked about in the Williams family.

Williams gained recognition as an athlete at the prestigious Wimbledon tournament, rather than on the messy fields of Cardiff Arms Park or Bridgend. At the age of 17, he achieved victory in the 1966 British junior tennis championship at Wimbledon, defeating David Lloyd in the final match.

While attending Millfield School in Somerset, a renowned school for rugby, Williams, whose father was the club president and doctor, was already making a name for himself in the sport in Bridgend. This was also where he met future Wales scrum-half Gareth Edwards, who was also a student at the school.

After departing from Millfield, Williams relocated to St Mary’s hospital in London and also spent some time with the London Welsh club. Despite having the option to pursue tennis professionally, he decided to stick with amateur sports and focus on his medical education. His father had advised him that it would be difficult to sustain a career as a professional athlete.

As a teenager, he was summoned to join the Wales team for a tour of Argentina in the summer of 1968. There were high hopes for the young player, John Williams, when he made his first appearance for Wales against Scotland at Murrayfield in February of the following year.

The Welsh team gained a new leader in their previous captain Clive Rowlands. In their 17-3 victory, Barry John, playing at fly-half, scored the final try. This marked the beginning of a successful era for Wales in the 1970s. With Phil Bennett as Barry John’s successor and JPR paired with wings JJ Williams and Gerald Davies, Wales became a dominant force in northern hemisphere rugby. JPR, known for his signature Elvis-Presley inspired sideburns, long hair, and tendency to wear his socks pulled down to his ankles, was the heart of their team.

His attacking abilities and strong defensive skills set him apart and secured his spot as a key player for Wales from 1969 until his retirement from international rugby in 1981. He further solidified his reputation during the victorious British Lions tours to New Zealand in 1971 and South Africa in 1974, playing in every Test match on both tours. Prior to this, Williams had experienced defeat with Wales on a tour to New Zealand in 1969, but the Lions’ 2-1 series win over the All Blacks two years later brought great relief.

In Auckland, he sealed the series with a drop-goal from a long distance in the last Test. His teammates were caught off guard, but his understudy full-back, Bob Hiller from England, had playfully teased him during the tour, saying he couldn’t truly call himself an international player until he successfully made a drop-goal.

Three years after, in South Africa, Williams once again showed heroism as Willie John McBride’s team emerged victorious in a series over the Springboks that was often marked by brutality. The Lions’ use of “99” as a signal often resulted in full-blown fights, and the image of Williams charging upfield to strike the significantly larger South African lock Moaner van Heerden was unforgettable. However, as Williams later admitted, it was not something he was particularly proud of.

Williams earned 55 appearances for the Wales national team, serving as captain for five of them during the 1978-79 season. He was awarded an MBE in 1977. In addition to his successes with the Lions, he also contributed to the Barbarians’ historic win against the All Blacks in 1973, scoring the final try. After retiring from international play, Williams continued to play for Tondu Rugby Club as a back-rower until the age of 54 in 2003.

In 1973, he married Scilla Parkin whom he met during medical school. From 1986 to 2004, he held a prominent position as a trauma and orthopaedic surgeon at the Princess of Wales Hospital in Bridgend. While many retired players often become commentators, Williams preferred to discuss his successful career, particularly his 11 victories against England.

Scilla and their children, Lauren, Annie, Fran, and Peter, are the ones who continue to live after his passing.