E

Those who were raised with a tape deck have fond memories of mixtapes, also known as compilation tapes in the UK. They recall the process of carefully selecting and arranging songs from records or CDs to create the perfect message. In Nick Hornby’s novel High Fidelity, the protagonist Rob Fleming had strict guidelines for creating a mixtape, such as avoiding consecutive songs by the same artist unless they were intentionally paired together.

Britt Daniel, lead singer of Spoon, recalls his first romantic relationship where he and his girlfriend exchanged a cassette tape back and forth. They would each add a song to the tape and then return it to the other person after a few days. These songs were like messages to each other and although Britt admits his communication skills were not the best, it was a sweet gesture.

Adrian Quesada of Black Pumas expressed that he used to attempt to make a strong impression by incorporating a diverse range of music genres. He had knowledge in jazz, so he would include some jazz in the mix. He also made sure to have a few ballads and some hip-hop, specifically A Tribe Called Quest, to appeal to a female audience.

Mine were a succession of tapes of mid-80s indie and old psychedelia. I’d sneak into the office at Boots in Slough, where I worked in the holidays, photocopy fragments of book covers and postcards to make a collage cover to wrap around the J-card insert, with the title on the spine – each one was numbered entry in a series called Never Say No to Perfect Popcorn – and then send to whichever beneficiary I felt most deserving.

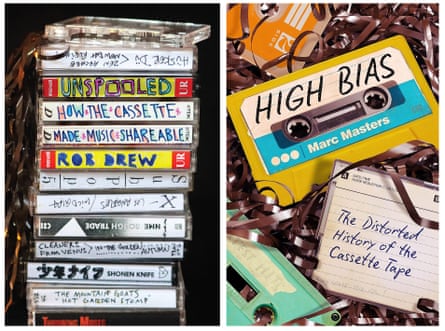

Mixtapes, though, were just one way the cassette had a seismic impact on the music industry, as explored in two new books – Unspooled by Rob Drew and High Bias by Marc Masters. The format instilled fear of piracy in the music industry, yet did more than any prior invention to spread music around the world.

In countries with emerging markets, where large music companies held a monopoly, cassettes were used to distribute music that was not deemed commercially viable by these corporations. This led to the rise of different music genres, such as Syrian singer Omar Souleyman who started as a wedding singer and had his sets sold on cassette at markets. Through the discovery of his music by Western tape collectors, he gained international recognition. Cassettes also played a crucial role in promoting hip-hop and thrash metal, as well as creating a small economy for go-go music in Washington DC. Even today, cassettes remain the preferred medium for lo-fi and experimental music.

Masters explains on a video call, while sitting in front of a shelf filled with tapes, that cassettes served various purposes. The primary one was granting both listeners and artists the freedom to curate their own musical experiences and share them with others. This medium allowed for a more personalized listening experience, rather than one dictated by external sources. Additionally, it provided musicians with a means of distributing their music without relying on labels or costly studio sessions.

These devices can be seen as more than just a means of listening to music. They also served as weapons against oppressive regimes. According to Drew, the spread of cassettes in the 1970s and 1980s had political implications in certain countries, particularly authoritarian ones like the USSR and Poland. The use of cassettes allowed for the spread of not only music, but also propaganda.

However, cassettes were not able to exist without the necessary hardware. They became the most popular format for hip-hop music after the creation of the boom box and car stereo. In his book, Masters discusses how car services in New York marketed themselves based on having the latest mixtapes, which often included shout-outs from featured MCs. The invention of the Walkman made it possible for individuals to listen to music on the go and became a popular way to share mixtapes. The Tascam Portastudio, a budget-friendly recording device that allowed musicians to mix down four tracks onto a cassette, also played a role in the rise of home recording. Even Bruce Springsteen used a Portastudio to record demos for his album Nebraska, as he felt that full studio versions with his band couldn’t capture the desired mood.

The spread of the format was influenced by a combination of generosity and practicality from its creator. The initial “compact cassette” was created by Lou Ottens from the Dutch company Philips and was introduced in 1963 (it was marketed as a tool for recording speech, not music). Its main advantage was not its sound quality, but its portability and user-friendliness compared to the previous reel-to-reel tapes. In order to ensure its dominance in the market, Philips licensed the invention to other companies.

Is Philips the most significant company in the history of recorded music, considering its creation of both the cassette and CD? According to Masters, there is a strong case to be made for that. It is also interesting to note that they pursued the development of the CD format, despite knowing it could potentially replace the cassette. This shows a level of foresight and adaptability, unlike companies such as Blockbuster who clung onto renting videotapes for too long and were eventually overtaken by new technology.

There have been claims of the cassette’s return for several years, but they are exaggerated. While sales in the UK have increased in the past decade, they only reached 195,000 in 2022, according to the BPI. In the US, sales also rose by 28% to 440,000 out of a total of 79.89 million physical album sales. Most of these sales are from major labels, which bothers Masters. He explains that the main reason for releasing pre-recorded cassettes currently is their low cost. However, major labels can sell them at a higher price than necessary without concern.

However, he acknowledges that the major labels’ involvement in cassette production is beneficial in sustaining the medium. This, in turn, benefits underground labels and artists for whom cassettes are still essential. He is willing to tolerate some hipster influence if it supports the more significant aspect of the situation.

Fernando Aguilar, a co-founder of Stay Tough, a cassette label focused on California pop-punk, is one of the individuals involved in this meaningful project. He initially ran a label that focused on hardcore, power violence, and grindcore music. According to Aguilar, the lo-fi nature of hardcore music makes it suitable for being dubbed onto cassettes, CDs, or vinyl without any noticeable difference. However, for emo and pop-punk, there is a nostalgia factor that makes cassettes a preferred format. Aguilar also mentions that working with screamo bands has shown him that they have a strong preference for cassettes because it adds warmth and enhances the lo-fi quality of their music.

For a label such as Stay Tough, working on cassette is also a matter of economics. The usual run is about 50 copies, and breaking even is “punk gold, right there”. That’s a lot easier when your main outlay is blank tapes, rather than pressing vinyl. At the moment, Aguilar says, he’s paying about $1.16 (92p) per blank tape, and 50 cents for a case. Vinyl, by contrast, is likely to have a minimum run of 100 units and to cost much more. The Musicol Recording Studio in Columbus, Ohio, for example, quotes $1,345 (£1,079) for 100 12in records in plain white paper sleeves. And with cassettes, Aguilar doesn’t have to join the long queue for vinyl pressing plants (currently six months at Musicol) – he can go from getting the recording from the band to having a cassette ready to sell in a fortnight, then sell them for between $4 (£3.20) and $8 (£6.40) apiece.

The mainstream trend has even impacted the underground scene. Aguilar observed a surge in cassette tape interest following the release of the Marvel film Guardians of the Galaxy, where the character Peter Quill frequently played an old mixtape. This trend was also seen in 2014 when a mixtape was featured in the TV show Over the Garden Wall. As a result, there has been an increase in people using cassette tapes.

Stay Tough also has a Bandcamp page where fans can download music. When asked if he believes people actually listen to his bands on cassette, Aguilar responds with a laugh. He explains that people mostly buy them to support the musicians and for the album cover, as well as for the aesthetic appeal. However, whether or not younger kids actually play cassettes is uncertain and Aguilar personally does not think so.

The cassette is still thriving, despite lacking the charm of vinyl and the high quality of CDs. As long as there is an underground music scene and a demand for physical copies, it will persist. Home recording and distribution through tapes has actually aided the music industry rather than harming it.

-

Marc Masters’ book, High Bias (published by The University of North Carolina Press for £20.95), is available for purchase at guardianbookshop.com to help support the Guardian and Observer. Additional fees for shipping may apply.

Source: theguardian.com