In 1966, Armand Schaubroeck – an ex-con who had made a local name for himself selling guitars out of his mum’s basement in Rochester, New York – tracked down Andy Warhol with an idea: a rock opera about Schaubroeck’s experiences of the US prison system. “He said, ‘how’d you get my home number?’” Schaubroeck laughs. “I said I called up the Rundel library [in Rochester] and looked him up in the Who’s Who. He goes: ‘My phone number is in there?!’ But he was fascinated – he wanted me to come to New York immediately.”

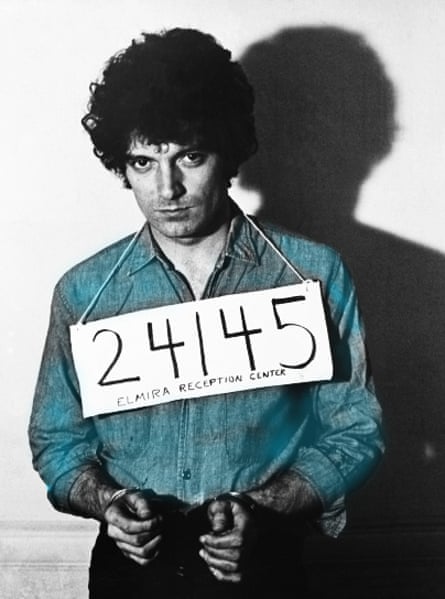

Aged 17, Schaubroeck had been sentenced to three years at Elmira State Reformatory, a maximum security prison in New York. He had come from a difficult home: his father, a Belgian immigrant, was confined to a veteran’s hospital with severe post-war PTSD. With no father figure and scarce money, “it eventually led to crime”, he says. At 14, he became part of a gang – “we had rules: we never stole from kids, just places that were insured” – that was eventually busted for 32 burglaries and imprisoned in the harshest of environments. In Elmira as inmate #24145, Schaubroeck saw things – extreme violence, sexual assault, suicide, corruption, insanity, mental deterioration – that left a permanent imprint upon his release on parole after 18 months. “I didn’t come out screwed-up or nothing. But your feelings disappear. You leave with a little bit of coldness in you.”

With the help of his brothers Bruce and Blaine, who had already recorded together with Schaubroeck as garage rockers the Churchmice, he turned an injured psyche into art. Not as catharsis; he felt it was important to let people know what prison was really like. “I really did, because no one has any idea. It’s a brutal, sick society.” Schaubroeck thought such a streetwise story would appeal to Warhol’s perspective, and he was right – Warhol wanted to make an off-Broadway play, perhaps even a film. But it eventually became the debut album from Armand Schaubroeck Steals: A Lot of People Would Like to See Armand Schaubroeck … Dead, which has been reissued for the first time, for its 50th anniversary.

It is a fascinating document of teenage decline and the disastrous dysfunction of the state: a two-hour double album of 1950s rock’n’roll, Velvet Underground-style rock and old blues, punctuated with 22 spoken-word scenes ad-libbed by Schaubroeck and “my actual crime partner” Dan McCabe, with help from brother Bruce, who also played drums. It tells the story arc from his arrest to his parole in raw detail, like a warped Jim Steinman writing about youth delinquency for the New York art crowd.

It began Schaubroeck’s short career as a proto-punk provocateur: equal parts Lou Reed-esque rocker, beat poet and performance artist. Alt-pop follow-up I Came to Visit; But Decided to Stay (1975) was a narrative about a priest killing a suicidal nun to save her soul before determining to live on her grave so they could be together (“probably my Catholic background or something”), whose lead single was a cover of Auld Lang Syne; his final album, 1978’s Ratfucker, was a brilliantly disturbed junk rock record about the depravity of man. It made him a celebrated cult figure, with fans in Julian Cope, Tim Burgess, Lydia Lunch, Fat White Family and the Lemon Twigs.

Simultaneously, Schaubroeck, with the help of his brothers, built up his business selling guitars out of his mum’s basement, initially to kids excited by Beatlemania. He turned it into a Rochester institution – once he overcame public suspicions: “It spread everything was ‘hot’, because I was an ex-convict, but it wasn’t true.” Known for zany TV commercials that featured the likes of Ramones, his enduring shop House of Guitars has hosted rock royalty (Ozzy Osborne, Brian May, Lemmy, Metallica) and boasts impressive memorabilia on its walls (John Lennon’s military jacket; a pair of Elvis Presley’s pants that once belonged to Paul McCartney).

House of Guitars is celebrating its 60th year, and the twin anniversaries mean Schaubroeck, now a youthful, good-natured 80-year-old, is looking back. He hadn’t listened to his debut in half a century. “It was very authentic,” he says, dressed in plain black shirt and glasses as he speaks on video from the shop. “I was remembering the times back then. It was all hippies. And this was the opposite. It was no peace and love. I was just trying to make jail as real as I could.”

Schaubroeck’s lyrics don’t flinch at the grimness of his prison experiences, though he undercuts this with subversive humour (the band’s acronym reads ASS). The album starts with him going to confession (“I knew I was going away and wanted some peace of mind”) and touches on everything he saw: the stabbings, rapes and suicides; the brutality of the guards, “old Ku Klux Klan guys that don’t like anybody”; the prison psychologists that would goad inmates by asking them if they had committed incest with their mothers and sisters. “They gotta find out quick if you’ve got a temper. They want to rile you up.”

There was also a love story with Suzie, Schaubroeck’s girlfriend who promised to wait for him. Was she real, too? “I changed the name, but yes. She ended up marrying a police officer,” he says, laughing.

Warhol saw the potential in the story and took a shine to Schaubroeck. “He was very intelligent, kind of quiet at first,” Schaubroeck says. He became a semi-regular at the Factory, Warhol’s counter-cultural hub, and remembers going there to play back a rough version of the album. “Everyone was kind of ignoring it,” he says. “Then Young Boy came on.” He sings the lyrics: “‘Not the young boy / The way he looks at me / The way he holds a cigarette / Reminds me of my wife at night.’ They all charged to the tape recorder – Andy, the painters, the French art directors. Andy was asking me stuff. And I said, ‘Well, gays are in demand in prison.’ Andy said: ‘We should go there!’ He was always kidding around.”

Schaubroeck didn’t get too involved in Warhol’s fabled party scene, something he now regrets. “I wanted to keep it business. But I didn’t realise that’s how he sells people, at those parties.” Schaubroeck was reluctant about Warhol’s idea of turning the album into a musical, as the seven-days-a-week commitment meant he would have to give up his guitar shop; Warhol’s attempts to broker a film deal – “something got quite close” – ended when he was shot by Valerie Solanas in 1968.

During Warhol’s lengthy recovery, Schaubroeck moved on to recording the album himself, but not before sounding out Norman Mailer to see if he wanted to write the story (“he had some interest, but he wasn’t sure of what”) and running for the New York Senate in 1972 as a Liberal party candidate. “They asked me and said: ‘Do whatever you want.’ They were just trying to make noise.” He ran on a platform of prison reform and gay rights, and created bumper stickers that read: “Vote for Armand Schaubroeck, learn a new lick.” It was a play on his guitar shop, “but homosexuals took it another way,” he says smiling.

after newsletter promotion

Of the four studio albums that referenced his confinement, none was more scandalous than Ratfucker, an expletive-ridden assault on decency that amalgamated the moral decay he’d witnessed inside. “I just took the inmates and put them together to create a person,” he says. The album starts with the depraved titular character stealing babies and selling them to would-be parents for $4,000, and songs then move from one degenerate persona to the next: drug dealer, sexual abuser, pimp, hitman. To get into the deranged headspace for recording, he “drank a quart of whiskey” and set up two mics either end of the studio. “I’d pace and mumble at the same time: ‘Maybe I’ll put something in her drink!’ or ‘I’ll just run ’em over with a fucking garbage truck!’ It gave a good effect.”

For all its knowingly Rocky Horror-esque exaggeration, it was shocking, and deliberately so: the sleeve notes read “I doubt you’ll ever hear this record on the radio”.

“We didn’t care about that,” he says. He appreciates it might not sit well with some modern sensibilities. “I saw it as theatrical, rather than just writing a love song. It’s a concept.” Yet he always seemed to be drawn to –

“Murderers?” he jumps in, laughing. “Crime? I learned so much about it!”

Schaubroeck never released another album – “I got into more responsibility at the store” – but never stopped writing and recording. In 2014 he released a surprise 13-minute Record Store Day single about the Vietnam war, God Made the Blues to Kill Me; intriguingly, he has a new album nearing completion.

It’s been a “stop-start” project recorded in the store’s basement over many years, he says, constantly put on hold for years at a time due to other commitments. Unlike his previous work, it isn’t conceptual – “they stand alone as individual songs” – except for I Got So High and No Junkies in Shangri La, two connected tracks recorded with Ginger Baker (“a good guy, I liked him”) when the late Cream drummer visited House of Guitars to host drum clinics. “They are kind of anti-drugs – the guy overdoses in the song.” Others, such as The Ballad of the Church Mice (Will Make the Girls Scream) refer back to his first band when Schaubroeck was rebuilding his life, post-prison.

But that was a long time ago, and he wants to clarify something. “When I talk about my stealing, don’t get me wrong – I am embarrassed by it. I wouldn’t think of stealing today. But when I got out of jail I thought ‘if I exerted all my energies on something else, I’ll do much better.’”

Source: theguardian.com