I

In the summer of 2011, I was in Norway covering a music festival for NME. At a party in another writer’s hotel room, I struck up a conversation with an American named Zach Kelly who wrote for Pitchfork. As a 22-year-old music enthusiast, it felt like meeting a player from my favorite football team. Zach graciously allowed me to ask him about his work as an intern at their Chicago office. It was an exciting experience to meet someone from a publication I considered unattainable. Upon returning to the UK, I received an email from Pitchfork’s editor, Mark Richardson. Zach had recommended me and asked if I would be interested in reviewing albums for them. NME declined, but Mark persisted and a year later, Pitchfork offered me a position as their first UK member of staff as an associate editor. I eagerly accepted the opportunity.

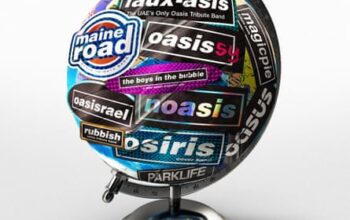

I am sharing this anecdote because it is one of many similar ones: The team at Pitchfork was highly dedicated to investing in up-and-coming critics, writers, and editors who were instrumental in discovering and documenting the defining alternative artists of the 21st century. This website, founded by Ryan Schreiber in 1996, evolved into a respected and professional outlet. One could argue that not since the prime days of NME had a music publication developed such a unique reputation, thanks in part to its well-known scoring system and bold reviews. “Pitchfork” even became synonymous with a particular type of music and music enthusiast: avant-garde before artisan culture became mainstream; somewhat intimidating and exclusive; perhaps you loved to hate it, yet still visited the site multiple times a day.

The media corporation Condé Nast acknowledged the significance of this when they acquired the company in 2015, causing some to question the potential consequences. How would an independent publication featuring niche music fare under the ownership of a larger corporation? And why did Condé’s chief digital officer, Fred Santarpia, boast to the New York Times about the acquisition bringing in a “very passionate audience of millennial males,” despite the website’s expansion to cover a variety of music genres beyond its initial focus on indie rock?

After eight years, Pitchfork has met the expected fate that many new media companies face. On January 17th, Anna Wintour, global chief content officer for Condé and editor of US Vogue, sent an email to staff announcing that the Pitchfork team will now be incorporated into the GQ organization. As long-time employees shared news of their layoffs on Twitter, including executive editor Amy Phillips who had been with the company for over 18 years, it was unclear what would become of the remaining team and their vertical on the GQ website. This is a saddening situation on multiple levels, particularly due to the job losses during a difficult time for media. Pitchfork was one of the few stable music outlets left, leaving many wondering where the former staff and hundreds of freelancers will turn to next.

Incorporating Pitchfork into a men’s magazine reinforces the idea that music is primarily a leisure activity for men, disregarding the contributions of women and non-binary writers such as Lindsay Zoladz, Jenn Pelly, Carrie Battan, Amanda Petrusich, Sasha Geffen, Jill Mapes, Doreen St Félix, Hazel Cills, and the editorial work of Jessica Hopper and Puja Patel, who transformed the website in the 2010s. This also reduces music to a mere component of consumer culture, rather than recognizing it as a distinct art form that brings together niche communities and deserves in-depth analysis and investigation. In fact, it was Pitchfork’s Marc Hogan who reported on allegations of sexual misconduct against Arcade Fire’s Win Butler by multiple women (though Butler claims the relationships were consensual). Additionally, Pitchfork published writer Amy Zimmerman’s report on 10 women accusing Sun Kil Moon songwriter Mark Kozelek of sexual misconduct (which Kozelek denies). It remains to be seen if GQ will devote resources to similar investigative reports, or if they will continue to focus on lifestyle articles like “The Best Cordless Stick Vacuum Will Turn You Into a Clean Freak” in their culture news feed.

Pitchfork has several flaws including questionable reviews in its archives, as well as recent biased and non-historical coverage. It also has a strong sense of gatekeeping, but it faces tough competition from other reputable sources such as Stereogum, Consequence of Sound, the Quietus, NPR Music, and the resurgence of blogging and newsletters. However, as the largest player in the field, its potential dissolution is akin to the disappearance of HMV from the high street. Without a prominent example to rally around, set oneself apart from, or debate over, the idea of viable specialized music journalism begins to dwindle into obscurity. This is an issue that has already been experienced in the UK with the disappearance of NME and Q magazine from store shelves, with the latter recently being sold and revived as a subpar blog.

Some have lamented Pitchfork’s poptimist shift over the past decade – where it once only reviewed Ryan Adams’ cover of Taylor Swift’s 1989, not the original, now pop is a key fixture – and you could argue that it is a less specific proposition than it was in its late-2000s heyday when it became synonymous with the likes of Arcade Fire and Grizzly Bear. But that shift represents the voracious reality of modern music consumption, and Pitchfork was the only music outlet dedicated to publishing two to four long-form reviews of new records every day, highlighting everything from the latest indie and rap records to fiercely niche work, and always introducing new writers to the fold. I can’t tell you whether “Hanoi conceptualist” Aprxel’s Tapetumlucidum

Having written numerous reviews, I am well aware of the amount of effort that goes into them. Each review goes through two editors, fact-checking, and final reads, showcasing a level of meticulousness that can greatly benefit young writers. Every edit serves as a valuable lesson that stays with them. For instance, the Features editor Ryan Dombal’s careful guidance on my first lengthy piece for the site in 2012 taught me how to write profiles effectively. Despite being a target of criticism from musicians, Pitchfork plays a crucial role in the music industry. It exposes artists’ work to a wider audience, creates myths and narratives that leave a lasting impact on listeners, and bridges the gap between recognizing good music and appreciating a good artist, as pointed out by Popjustice’s Peter Robinson. Moreover, it treats artists with the respect they deserve by providing a thorough and fair critical analysis, even if it may be negative. A positive Pitchfork review can propel an artist to a larger audience, as seen with Mike Powell’s review of Courtney Barnett’s 2013 single “Avant Gardener,” Sasha Geffen’s review of MJ Lenderman’s album “Boat Songs” in 2022, or any review by experienced rap critic Alphonse Pierre. On the other hand, it can also change the perception of an artist, as demonstrated by Jessica Hopper’s exceptional review of Lana Del Rey’s 2015 album “Honeymoon.”

Avoid the newsletter promotion.

after newsletter promotion

Why do I need Pitchfork when I can read thousands of words about the same topic in the Guardian? However, music publications that specialize in a certain genre or niche can offer unique perspectives and coverage that generalist outlets cannot. For example, Pitchfork surprised me by accepting a pitch for a review of an extremely obscure album, which I wouldn’t be able to write for a generalist outlet due to its lack of cultural significance or relevance in current news. Writing this piece allowed me to reach out to the national library of the artist’s home country for newspaper clippings from the 1980s and their original record label for any relevant artifacts. I also had the opportunity to scour through obscure online forums and dig through dusty archives for information that would be of interest to a wider audience. This type of in-depth coverage and research holds value that may not be evident to parent media companies focused solely on financial gain. Unfortunately, these companies often condemn platforms that don’t meet their constantly changing expectations (such as the “pivot to video” trend) and contribute to the decline of quality content on the internet. While we don’t know what the partnership between Pitchfork and GQ will bring, there is a clear contrast in values between a publication that prioritizes critical analysis and one that revolves around celebrity access.

Attempting to evaluate the problem from Condé’s corporate perspective defies logical reasoning. Pitchfork was known for its agility and quick pace, with one of Condé’s audience development editors tweeting that it had the highest daily site visitors out of all their titles, despite lack of resources provided by the company. Such nimble publications can serve as indicators for parent companies to test out new ideas on younger, receptive audiences, potentially leading them to other more stagnant titles. However, it is possible that Pitchfork’s rapid growth and embrace of diverse representation may have been too much for the conservative leadership, causing a decline in its male audience who have aged from their 20s to 40s without bringing in enough new readers to sustain a clearly-defined marketing demographic. If this is the case – questioning who music criticism is truly for – perhaps Condé should take a more daring approach in attracting new readerships and generating revenue, similar to the bold move made by acquiring Pitchfork and giving voice to new perspectives both on the mic and behind the keyboard.

Source: theguardian.com