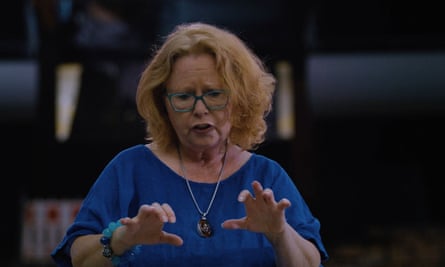

‘I went face to face with Keith Jarrett,” recalls Vera Brandes, “and I said to him, ‘Keith, if you don’t play this concert, I’ll be fucked. And you’ll be fucked too.’” Brandes laughs as she recalls this pivotal conversation, 50 years later. It came after a day of chaos where she, an 18-year-old concert promoter, was desperately trying to convince the famously temperamental jazz pianist to play a concert on a substandard instrument.

“To be honest,” she adds, “I had absolutely not a single clue what those words meant! My English wasn’t then as good as it is now. I’d heard Miles Davis using the f-word while talking to his band, which featured Keith Jarrett, a few years earlier, so maybe I was channelling Miles. Keith must have been floored to hear this teenage girl who looked like Brigitte Bardot’s little sister using this kind of language!”

This much mythologised encounter happened in January 1975, when Jarrett turned up at the Cologne opera house to play the biggest solo gig of his career. Instead of the 10ft-long, half-ton Bösendorfer Imperial he’d been expecting, Jarrett had been given a 6ft baby grand rehearsal piano with a thin tone, a non-functioning damper pedal and no power in the bass register. A furious Jarrett wanted to cancel but – after much coaxing from Brandes, and the diligent work of two piano technicians – he reluctantly stayed to perform a completely improvised one-hour set.

Despite the setbacks, the gig was a triumph, and ECM’s live recording of the show went on to become the bestselling solo jazz album – and the bestselling solo piano album – of all time, shifting more than 4m copies to date.

Half a century later, the story of how Jarrett was forced to adapt his playing for a shonky instrument has inspired dozens of inspirational lectures from business gurus on how to use obstacles creatively. It has also inspired not one but two movies, both due for cinematic release this year: a loosely fictionalised drama, Köln 75, about Brandes and the events of the day; and a forensic, feature-length documentary, titled Lost in Köln, that searches for the iconic piano and negotiates dozens of conflicting accounts of the concert.

One person who does not celebrate the concert is Jarrett himself. Aged 79 and recovering from a series of strokes in 2018 that left him partially paralysed, the pianist has long dismissed his best-known work. He’s described it as repetitive, and said he’d like to destroy all copies of the LP.

“It must be infuriating for a great musician to be constantly asked about this one gig he did decades ago,” says Vincent Duceau, director of Lost in Köln. “Like being a great painter who – instead of talking about your most complex work, made at your full capacity – is constantly asked about a little squiggle you drew in the corner of the table. It shows a side of him he doesn’t want to show. Of course he doesn’t want to cooperate with us, which is fine.”

Köln 75 was also made without the cooperation of Jarrett or Manfred Eicher’s ECM Records. “I get why Keith wants nothing to do with us,” says Ido Fluk, the film’s writer and director, who draws a Radiohead analogy. “The Köln Concert is his Creep, his big hit that he wants to disown. That’s why the film isn’t really about him. It’s about Vera Brandes.”

Although only 18 when she hired the Köln Opera House for this gig, Brandes was already something of a veteran promoter. Aged 16, while still at school, she met the British saxophonist Ronnie Scott at a jazz festival, and he asked her to book him a two-week tour of Germany. “I was using the phone line in my father’s dental surgery,” she says, laughing again. “I had to develop this tough front to negotiate with venues. And I realised I was quite good at it.”

Within a year, she was booking her favourite jazz acts to play theatres and university venues around Cologne. Her New Jazz in Köln series welcomed the likes of Ralph Towner’s Oregon, Ian Carr’s Nucleus, Barbara Thompson and a quartet featuring Gary Burton and Pat Metheny. Almost singlehandedly, this teenage fan had made her city a fixture on the jazz circuit.

“This, for me, is the real story behind The Köln Concert,” says Fluk. “There’s a whole village that helps to create every work of art. Think of the people who erected the scaffolding that Michelangelo stood on as he painted the Sistine Chapel. My film is about this gutsy teenager who created an entire scene. We tell her story as a series of chaotic events, in the style of 24 Hour Party People. And Vera’s been a pivotal figure in German music ever since – a producer, promoter, record label boss and now a music therapist. Even today, if you talk to anyone involved in German jazz, she is a goddess. Without Vera, there’s no Köln Concert.”

One musician who has immersed himself in the events of that day is the British pianist Dorian Ford. After spending years studying Jarrett’s solo improvisations, he was in Cologne to play an improvised set inspired by The Köln Concert on 24 January, its 50th anniversary – not in the opera house, which is undergoing renovation, but in a church around the corner.

“The Köln Concert was totally improvised,” says Ford, “but not what we understand as ‘free improvisation’. It’s tonal and melodic. It has a structure, and it transcends the boundaries of music-marketing. Jarrett described his solo improvisations as ‘universal folk music’: I can hear the sound of rugged American individualists, like Charles Ives and Scott Joplin, but I can also hear hymns, gospel music, country music, honky tonk, anthemic songs, soul, blues, stride, boogie woogie, modal jazz and plenty of classical music. This is not a European culture of deference. This is high-end, elite music, but presented with an audacious, American, heart-on-sleeve populism.”

Ford doesn’t think the piano actually sounds that bad, and the technicians had clearly addressed most of its problems. “The one thing is it sounds a little tinny, and he has to hit it hard. If you listen to Jarrett’s solo concerts from Bremen or Lausanne, recorded 18 months earlier, they’re technically superior in many ways. But the Köln piano lends a mystical, magical edge.”

Brandes recalls the chaotic hours before the concert. “For starters, Keith had played a gig in Switzerland the night before,” she says. “I’d actually bought him a plane ticket, but, unbeknown to me, he’d cashed that ticket in at Zurich Airport for 375 deutschmarks and got a lift in Manfred Eicher’s tiny Renault 4, to save money. So, after an eight-hour drive, Keith was exhausted and had a bad back. When I showed Keith and Manfred the piano, they walked around it a few times, played a couple of notes and said, ‘Unless we get another piano, this concert is not happening.’”

She spent feverish hours trying to obtain a concert grand from the local university, and was even preparing to push it over the cobbled streets of Cologne, but the piano-tuner warned her this risked destroying the instrument. “So we had to trust the piano-tuner and his son. They managed to take the baby grand apart, fix it, reassemble it and tune it. Somehow they did all of this on either side of an opera show that was happening before the concert! By 11.30pm, they had got it into shape.”

Brandes remembers a hip, young, bohemian audience turning up to this late show: “We sold all 1,432 seats, which was astonishing.” Jarrett did no rehearsal, and bootleg recordings suggest that it was unlike any of the other solo shows he played on this 13-date European tour.

One audience member, a nine-year-old Jan Fritz, had come from Bremen, 300km away, with his father. He remembers that the opera house played a four-note jingle on the tannoy before concerts, instructing patrons to take their seats. “The first few notes that Jarrett plays in the concert basically repeat that chime, and you can hear people in the audience chuckling with recognition,” he says. “What’s amazing is that he continues to develop this chime throughout, like a sonata. He’s responding to something he’d just heard, and composing as he goes along, which I still find remarkable. On the long drive home, I could still sing that theme.”

Why did the headstrong Jarrett eventually concede and play the show? “I think there are several reasons,” says Brandes. “First of all, Manfred Eicher had already paid Martin Wieland to record it, with two microphones, to take advantage of the unique acoustic of the opera house, so maybe there was pressure. But I think it was mainly personal pride. If Keith had cancelled he would have been in despair, sitting in his hotel, with 1,400 angry punters outside the theatre. He’s not the kind of performer who cares about his audience – he’s driven only by a love of his own art. But I think he would have been angry at himself if he’d failed to take on the challenge.”

Source: theguardian.com