T

Akashi Matsumoto and Haruomi Hosono had to make a decision in 1969 when they formed a rock band. They had to choose whether to sing their lyrics in English, the dominant language of the genre at that time, or in Japanese. After discussing it, they ultimately decided to use their mother tongue, ultimately revolutionizing their country’s music industry.

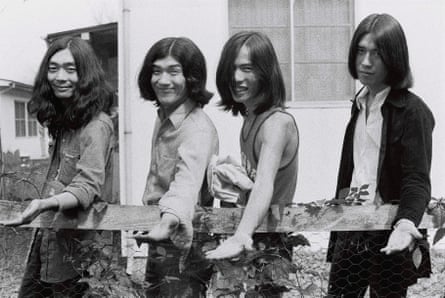

The collective known as Happy End, which included notable artists Shigeru Suzuki and Eiichi Ohtaki, combined elements of western folk-rock with Japanese lyrics, a choice that has had a lasting impact on various genres like the popular 80s funk genre “city pop” and present-day J-pop. In a meeting room with a view of Tokyo’s cityscape, 74-year-old Matsumoto, a member of the group, reflected on the unique challenges of translation. “As a Japanese native, my words hold a certain essence. Any attempt to change that through translation would alter the original meaning and take away from its authenticity.”

From 1970 to 1973, Happy End released three albums which have recently been reissued on vinyl. However, the impact of the band has endured for decades. They were praised by domestic critics from the beginning, with their 1971 album Kazemachi Roman being hailed as a masterpiece. It continues to be rated highly on lists of the best Japanese albums. According to band member Hosono, musicians during that time were inspired by artists such as Cream and Jimi Hendrix, causing them to imitate and compete with each other. However, Happy End chose to be unique by using their own words to create something original. Hosono eventually gained even more recognition with the synthpop group Yellow Magic Orchestra.

Happy End emerged from the band Apryl Fool, which Matsumoto and Hosono played in. While their psych-rock sound helped them stand out at a time dominated by groups replicating the sounds of the Beatles and the Monkees, Apyrl Fool’s lyrics were still sung in English – all except for a two-part song written in Japanese by Matsumoto: The Lost Mother Land, about the rapidly changing state of his hometown Tokyo, and everything lost alongside it.

According to Matsumoto, the 1964 Tokyo Olympics brought about significant changes. The previously existing rivers in Tokyo were filled in and there was an increase in construction of highways and freeways. Additionally, the removal of trams to make way for roads greatly altered the landscape. These developments led to a blockage of the sky, making it difficult to see from certain areas.

Singer Chu Kosaka joined the cast of the Japanese version of the musical Hair, prompting Apyrl Fool to disband. During this time, Hosono and Matsumoto became more interested in west coast rock bands like Buffalo Springfield, the Grateful Dead, and Moby Grape. They decided to form a new group influenced by this scene. Hosono invited Ohtaki, who brought a Beatles and Association-inspired melodic element to the group. Matsumoto recalls the moment when Ohtaki called Hosono, saying he finally understood what made Buffalo Springfield great, and they all shared the same vision, laughing about it.

Suzuki, the guitarist, completed the band’s members. When questioned about Happy End’s place in the Tokyo rock scene of the early 1970s, Suzuki explains, “We spoke our minds openly and fervently, without being stifled by adults. We were ‘innocent’ – that is the best way to describe our identity.”

Their first album received high praise for its unique blend of intense tones and Japanese elements, further fueling the ongoing debate known as the “Japanese rock controversy.” This debate questioned the authenticity of rock music if it was not performed in English. Determined to prove that Japanese rock could thrive, Happy End returned to the studio for their second album. “We refined our talents and explored various directions before delving deeper into them,” explains Matsumoto.

The resulting record, Kazemachi Roman, became synonymous with the more confident sound of Happy End. Matsumoto’s lyrics became more intricate, with a focus on the Tokyo he longed for before the Olympics. However, the most prominent aspect was the strong sense of collaboration within the band. Matsumoto highlights the song “Kaze Wo Atsumete” as a prime example, as it gained the band wider recognition internationally when it was featured in Sofia Coppola’s “Lost in Translation.” Matsumoto explains, “It felt like we were playing a game of catch with each other – we would change the lyrics, we would change the melodies, constantly refining and improving.”

Ignore the newsletter advertisement and proceed.

after newsletter promotion

Despite its later commercial success, Happy End, Kazemachi Roman received positive reception from critics and the art community, leading to a decrease in the “Japanese rock controversy”. Matsumoto reflects on the experience, stating that they believed they had done their best and then went on to explore solo work and spend less time together as a band, which he now regrets. Light-heartedly, he suggests Hosono may enjoy forming new bands, recalling one instance on the bullet train where he saw Hosono jotting down new band names.

The band Happy End recorded another album, also titled Happy End, at Sunset Sound Studios in Los Angeles. However, lead singer Matsumoto noted that the group was primarily thinking about their individual futures, which is evident in the music on the album. This was not a negative thing, but rather a natural progression.

Suzuki went on to have a successful career as a solo artist. Ohtaki also had a successful career as a popular artist and producer, continuing to release music until his death in 2013. Matsumoto became a well-known lyricist in Japan and collaborated with many popular musicians. Hosono had a diverse career, trying his hand at various roles in the music industry. This year, a compilation honoring his 50 years as a solo artist will feature covers by artists like Mac DeMarco. At 76 years old, Hosono continues to create and plans to start working on a new solo collection soon.

In the 21st century, the impact of Happy End’s legacy is even more significant. According to Matsumoto, in the past, new music had to pass through the US first before reaching other countries. But with the emergence of the internet and platforms like Spotify, people can now discover and enjoy music from any part of the world. The music industry has become more global, no longer controlled by one specific location or language. Happy End emphasized the strength of the Japanese language, but also stressed the importance of freely expressing oneself in any language. Matsumoto believes that individuals should use the language they feel most comfortable with to communicate their thoughts and feelings, regardless of their country. There should be no limitations or restrictions.

Source: theguardian.com