Five years ago, when the alternative artist Ekkstacy was 16, he stole two T-shirts from a record shop in a mall by his childhood house in Vancouver. They were both merch for Seattle bands: one was a Nirvana shirt, the other was an Alice in Chains shirt. “I was like, I’m not wearing this unless I know what this is,” he remembers. After listening to the artists, one of the shirts got a lot of use; the other was an Alice in Chains shirt.

Next month it will have been 30 years since frontman Kurt Cobain’s death in April 1994. Over these decades, there has been a natural and constant flow of artists name-checking Nirvana in interviews – Lorde and Lil Nas X count themselves as fans – or creating work that sounds similar to theirs, perhaps without even realising it. In the words of alternative singer-songwriter and performance artist Poppy, 29: “You can’t throw a dart and not hit a band who hasn’t been influenced by them.” But how did Nirvana become one of the most influential bands for a generation born after Cobain’s death?

Last year, 27-year-old rapper Kevin Abstract, previously a member of hip-hop boyband Brockhampton, released a Nirvana-inspired album called Blanket. In a big pop culture moment, Boygenius, the supergroup composed of singer-songwriters Phoebe Bridgers, Lucy Dacus and Julien Baker and arguably the biggest band of their generation, appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone recreating Nirvana’s 1994 cover shoot of them in suits, captured months before Cobain’s death.

Both the Rolling Stone team and band had the idea independently of each other. “Nirvana were responsible for injecting not just rock but popular music with new life at a time when a lot of the Top 40 seemed stale,” says Christian Hoard, the magazine’s music editor. “Boygenius are the vanguard of a newer era of bands keeping rock alive.” When Hoard grew up in the 90s, he listened to both Nirvana and classic rock. “Now Nirvana counts as classic rock, and kids are still listening. But it’s classic for a reason – those songs are timeless. They still sound fresh. And they get at something inside of us that’s ineffable.”

In the 2000s, kids learned about Nirvana through rock magazines and CD compilations. Before singer-songwriter Samia, 27, emerged as one of indie rock’s most poignant songwriters, she was a 10-year-old obsessed with Nirvana. She credits an early boyfriend who recommended them to her. “I had posters of a musician who had died by suicide plastered on my bedroom walls and was listening to Bleach every day. My dad was probably very concerned,” she laughs. In the 2010s, social media platform Tumblr birthed the first online nostalgia phase: gen Z rock journalist, DJ and presenter Yasmine Summan remembers the “pastel grunge” era of reposting images of rock music lyrics – girls in grunge-inspired outfits, cityscapes and cute iconography overlaid with a pink or pastel filter. It was mostly about romanticising grunge-era fashion, but still directed plenty of women and LGBTQ+ fans towards 90s alternative bands including Nirvana. Alexia Roditis, 24, frontperson of California punk rock band Destroy Boys, says they became a Nirvana fan after seeing a picture of Kurt Cobain in a dress on Tumblr: “I know that’s maybe the most gen Z answer I could give and it’s the truth!”

Today, says Summan, young people find Nirvana through the web of links between artists, streaming services’ rock playlists and fan accounts sharing fashion, lifestyle and culture from the 90s, along with fancams and video edits of Kurt Cobain. “With a lot of gen Z who missed the boat, myself included,” she says, “you can see in the way they talk and act, it’s about trying to relive that 90s era, trying to be a part of something they weren’t a part of. The Fomo is the way they express their love for them.”

In the 90s, Nirvana were effortlessly successful in a way that artists would struggle to be now in a world of social media marketing, streaming numbers and the barriers to entry for those who aren’t wealthy and well-connected. Something that retrospectively makes their career so alluring is that they were never supposed to be there. Nick Ruskell, longtime Kerrang! staffer and author of last year’s celebration of 40 years of the magazine, Kerrang! Living Loud, recalls that Nirvana’s breakthrough album, Nevermind, knocked Michael Jackson off the top of the Billboard chart when he was at the peak of his powers. “They were very organically transported from the underground to the room with Michael Jackson in, with their personality, clothes, awkwardness and piss-taking intact,” Ruskell says.

They wore ballgowns on MTV’s Headbanger’s Ball, performed their crude, raw track Territorial Pissings on Jonathan Ross’s chatshow instead of their hit Lithium and worked with Steve Albini to make In Utero, a rough, weird follow-up to their mainstream album. Those anti-celebrity moves are still perceived to be authentic and thrilling, as they were then. “They were the most visible of a new generation of bands who weren’t so enamoured by the idea of being in a band as a route to owning a gold helicopter, as rock stars [such as Mötley Crüe] had been in the past.” As Ruskell says: “This did just make them very cool.”

Just as the Beatles defined the construct of a rock band, Nirvana redefined what a band was – both in the public consciousness and to other musicians: unpretentious, tough and sensitive, embraced by the system while threatening it. “Nirvana were so big and their impact was so pervasive they shaped the idea of what rock’n’roll could be, how a record should sound, how musicians should act,” says Ruskell. Scenes have come and gone, but that concept of a band hasn’t been updated or evolved into anything new. (It’s notable that possibly the biggest name in rock since Cobain has been his bandmate Dave Grohl, who went on to form Foo Fighters.)

What has changed about the makeup of bands is diversification: more women and out queer and trans people play in bands than ever before. Nirvana – with their progressive politics and push for equality and respect – had a significant role in that. “The level of angst was unprecedented,” says Samia of their music. “And I think for a lot of teenage girls especially that strikes a chord.” When she looked beyond the music into Cobain’s published journal entries and interviews, she found that him speaking about feminism and issues of social justice drew her in deeper. “I found Kathleen Hanna and the whole riot grrrl movement through Kurt. That stuck with me.”

Cobain’s softness and empathy is something that spoke to the 26-year-old English singer-songwriter L Devine. “I remember being surprised to learn how much of a sensitive human he was and I think he was truly punk in that sense,” Devine recalls. “To be situated in what was predominantly a hyper-masculine corner of music and be so outspoken about sexism, racism and homophobia, bringing those messages into the mainstream challenged what it meant to be a rock star in that era – his ideologies have transcended generations.” The current young generation find his freedom of expression authentic. Alexia Roditis says Cobain’s values are infused in everything from performances to the content of the music: “I think people still need that, maybe even more so today than before.” That expression, they remark, is angry, melancholic, numb, depressed, hopeful.

For Poppy, Nirvana’s emotional impact is unlike anything she’s heard in a long time. “There’s a fearlessness that’s missing in a lot of current music. They represent no fear: scream if you want, cry if you want, break things,” she says. “Apparently they created an environment at their live shows that was very accepting of anyone: gay, straight, trans, any colour, and they had a very no bullshit ethos. Of course I wasn’t around for that – I just missed out on them, which is a wild thing to think about.” This sentiment is repeated by others too – a feeling that Nirvana are so big in their lives, so modern a cultural reference point that it’s odd their existences never crossed over. Their experiences with Nirvana are too big to have been posthumous.

Samia is not ashamed of saying she’s a descendant of such a major and obvious teacher as Kurt Cobain. “You might only be able to hear it sonically a little bit in my earlier songs, but what has lasted from him in my music is more in his lyrics – I spent so much time reading his journals,” she says. Now five albums into her career, Poppy feels similarly; her musical project and previous life as a viral multimedia artist have involved consciously adopting certain subcultural scenes such as heavy metal or experimental art pop. Playing with ideas of authenticity, artifice and replication is part of her methodology, which has led to comparisons to Andy Warhol. Have Nirvana found a way into her music? Of course, she says, but you won’t be able to pin it down. “If you’re gonna make a smoothie, come up with the most interesting ingredients but make them untraceable.”

Nirvana are a band, but they’re Kurt Cobain’s band – forever entangled with the size of his personality and the tragedy of his death. The myth of being part of the 27 Club – a group of artists including Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix who died by suicide or a high-risk lifestyle at that age – plays some unfortunate part in their appeal. The fact he’s the sandy-haired, blue-eyed poster boy of grunge doesn’t hurt. Cobain was a Pisces, which the astrologically inclined gen Z will know is the sign of compassion and spiritual sacrifice for others, typically associated with Jesus; in his own music and suicide note, he made that very comparison, calling himself “the sad little, sensitive, unappreciative Pisces, Jesus man”. Celebrities carry symbolic meaning of their own, and Cobain, with his open struggles with his mental and emotional health, is totemic of the difficulties faced by the modern disaffected masculine identity.

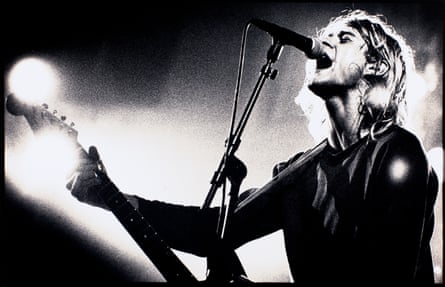

I was two years old when Cobain died, and remember having a large black and white poster of him playing guitar on my wall that looked like a photo you’d see on an order of service booklet. To young people who experience him through images, he is something like a Marilyn Monroe – almost a mythological being, or as Samia puts it, “it’s like worshipping an idol, thinking about someone like him”.

That was partly intentional: despite his anti-celebrity feelings, Cobain was conscious of the tools needed to make meaning in his art and legacy as a serious artist, and actively desired that his band become extremely successful. In the 2023 update of his Nirvana biography, The Amplified Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana, Michael Azerrad wrote: “Kurt, being a student of rock history, knew that the story of a rock band is essentially a legend – in the sense that there’s some wiggle room in the truth as long as it serves the overall myth.” He goes on to explain that in Cobain’s imagined grand opus, he fights antagonists and there was always another one to replace the last to blame everything on and rage against: his home town, bullies, his parents, homophobes, misogynists, racists, his own body, his record label, rock journalists. His greatest antagonist of all was himself: as he stated in the title of a 1993 song, he hated himself and wanted to die.

It’s easy to fall in love with a historical figure when you have a full and timelessly dramatic story. Nirvana never had the chance to make average albums or fall off into obscurity. Cobain never hit an awkward middle age. We only have the greatest hits and the idiosyncratic moments. For a generation hooked on nostalgia for seemingly every recent-enough decade they barely lived through – the 90s, the 00s, even the 2010s – Cobain is an emotional entry point into his decade. “If you didn’t experience 90s culture, it’s all an imaginary world,” says Samia. “We get to see that world through his lens, and I think it’s a particularly special lens, so I feel grateful for that. He’s a wellspring of nostalgia.”

If you’re picking up a guitar or drumsticks today and considering how you might start a band, you would probably look, as Ekkstacy did, to Nirvana as a template for how to do that successfully. The Canadian artist made his first collection of music alone with a producer. Next he wants to write and record with a group of musicians and is taking inspiration from how Nirvana made their debut album, Bleach. Why Nirvana, I ask, why not any other band of that era such as Pearl Jam or Soundgarden? Ekkstacy shrugs, trying to list the reasons – he loves the drums, melody, lyrics – and then just laughs and says, “What are you gonna say, they’re just better than everyone else.”

-

Hannah Ewens is the author of Fangirls: Scenes from Modern Music Culture (Quadrille Publishing, 2019)

Source: theguardian.com