‘W

“What have I accomplished? Have I embarrassed myself?” Terri Hooley responds sarcastically when I compliment him on his many successes. “I’m tired of being labeled as The Godfather of Punk – I’m not. I’m simply an aging hippie and punk was our way of getting back at you for not paying attention to us the first time around!”

I was informed that Hooley might be in a bad mood because of the frequent dialysis sessions he undergoes and his busy schedule, which included DJing at recent shows featuring the Northern Irish punk bands he discovered – the Undertones and the Outcasts – and promoting his newly released biography, Terri Hooley: Seventy-Five Revolutions, written by Stuart Bailie. However, when the topic of his biography is brought up, Hooley becomes enthusiastic. He expresses, “I think it’s fantastic!” The man who brought hope to the youth of the region by promoting punk during the Troubles is now full of charm and happy to reminisce about his extraordinary life.

Published in honor of Hooley’s 75th birthday on December 23rd, Seventy-Five Revolutions tells the story of a life marked by trauma and violence. Born in 1948 to a Protestant family in east Belfast, Hooley’s father was distant and strict. At the age of six, Hooley lost an eye in an accident, further deepening his sense of being an outsider. Music became a refuge for him, and by the time he was 17, Hooley was known as the top DJ in Belfast. He also gained local notoriety for his opposition to the Vietnam War, which included confronting Bob Dylan at his Belfast concert in May 1966 for not protesting the war through tax boycotts. Dylan famously told him to “fuck off.”

He has had numerous encounters with famous individuals, such as communicating with Bob Marley in the 1960s, organizing Shane MacGowan’s first performance in Northern Ireland (where he expressed concerns about the city and stated, “I will keep a low profile”), kissing Cilla Black, and physically confronting John Lennon. The incident with Lennon occurred during a trip to London in 1970, when Hooley was introduced to him by mutual acquaintances from Oz magazine. The ex-Beatle mistook Hooley for an IRA supporter and, in his pre-pacifist days, offered to provide him with weapons. Hooley admits that the encounter was not his proudest moment, as Lennon was under the influence of drugs. When Hooley later shared the story with Cynthia (Lennon’s first wife), she jokingly remarked, “You should have hit him harder!”

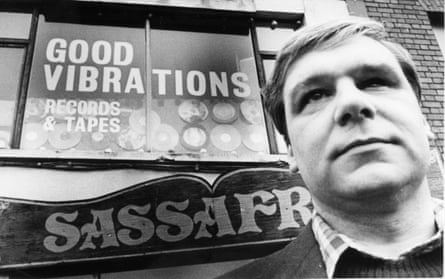

In the early 1970s, violence appeared to be breaking out all around him in Belfast. He remembers, “When I was growing up, there were 80 clubs. Then the Troubles began and all the venues closed and people went home.” Despite the worsening conflict, Hooley remained in Belfast and started counterculture magazines and pirate radio stations. An attempted kidnapping by armed individuals only fueled his determination to promote nonsectarianism. In 1977, Hooley and his friends transformed a abandoned building on Great Victoria Street into a record store, located on what was known as “the most bombed half-mile in Europe”. They named it Good Vibrations, after the popular Beach Boys song, which conveyed both hope and irony.

The success of the shop prompted Hooley to support and promote local punk bands. He followed through with this, stating that his goal was to unite people, inspire young individuals, and bring attention to Belfast’s music scene. The fourth single released by the newly established Good Vibrations label was from a relatively unknown band from Derry. Despite the potential he saw in them, Hooley faced rejections from major labels such as CBS and EMI when he tried to pitch their song, “Teenage Kicks.” Even Rough Trade, the largest indie label at the time, turned him down and deemed it the worst record they had ever heard. Feeling defeated, Hooley returned to Belfast, but then something unexpected happened. The influential radio DJ John Peel played the song twice in a row.

The Outcasts and Rudi, along with Teenage Kicks, are now considered iconic releases from Good Vibrations. These releases were a major part of a highly productive music scene. However, due to the label’s limited budget and Hooley’s disorganized approach to business, only the Undertones achieved mainstream success. Despite being a beloved figure in the local community for his passion, Hooley faced discrimination and violence for rejecting sectarianism. This was evident in the form of insults, death threats, and a brutal attack at Good Vibrations.

Hooley, currently residing in the outskirts of Bangor, experiences post-traumatic stress disorder. Due to past experiences, he has developed a habit of staying up until 2:30am, as the loyalist drinking establishments would close at 2am and he would remain awake to ensure his safety. Despite knowing that he is no longer a target, he still carries the emotional burden. Hooley also mentions that some of his former friends had joined paramilitary groups but later regretted their actions. The same paramilitaries who had attacked him have since become Christians and even apologized to him with cards.

In 1982, Hooley was declared bankrupt but remained involved in Belfast’s music scene until 2015 when his poor health forced him to close his final record store. During this time, he gained recognition through the Good Vibrations biopic, which was Mark Kermode’s favorite film in 2013, and a jukebox musical of the same name. The musical’s recent off-Broadway run received positive reviews from the New York Times. Hooley was also featured in the BBC documentary series Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland. It is quite remarkable for someone who admits to living a chaotic lifestyle fueled by substance abuse. Hooley expresses his disbelief at the fact that there is now a film, a musical, and a book all about him.

Bailie’s beautiful biography rightly celebrates this “Belfast Cyclops” who loves music and preaches unity while remaining indifferent to material rewards. “Good Vibrations existed as a little oasis of positivity when everything was awful,” Hooley says, “when our country was having a collective nervous breakdown. I was as mad as the rest of them but I wanted love and peace, not violence and hate.”

Source: theguardian.com