The New York artist Rammellzee was, without a doubt, one of the most intriguing visionaries of hip-hop culture from its mid-70s origins. Raised in the remote beach front outpost of Far Rockaway, Queens, the final stop on the storied A train, Rammellzee discovered the art of graffiti while noticing another teen spray-painting his tag, “Sonic Bad”, at 57th Street station. Already engaged in his own personal investigation of calligraphic writing, Rammellzee was instantly fascinated. He soon found himself descending into the dark underworld of subway tunnels where train cars stood motionless, throwing up his tag across the metal shells with only a haze of visibility to focus, anxiously aware of being nabbed by transit cops.

Rammellzee, a tall, lean Black and Italian-American mixed-race kid, bounded about with a distinctive style: a mélange of hip-hop flash and vintage soul musician funk – a look he would play with for his entire life. As a youngster in the mid-70s he joined the graffiti renaissance and invested in it a personal and wholly other critical perception, one that was entirely esoteric, if not otherworldly.

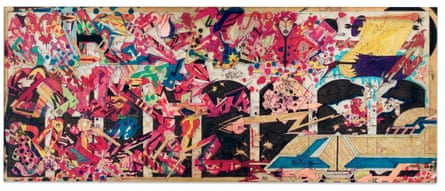

Employing concepts informed by the Five Percent Nation (an offshoot of the Nation of Islam) mixed with an innate tricksterism, he would come to define graffiti art as gothic futurism. In his train-bombing texts, he used the Greek alphabet – including writing the Sigma Σ summation symbol in place of the letter E – and also borrowed from the linguistic skullduggery of monks.

According to Rammellzee’s prolific reading, the monks’ intention had been to rescue the written word from the clutches of the bishops, the ruling elite of church and state, who used literacy as power, prohibiting it from the common people. The monks would reshape the alphabet into illuminated, pictorial coding, concealing the language in realms where bishops feared to tread. As soon as the bishops realised the unreadable works acted as subterfuge they banned them outright.

As far as Rammellzee was concerned, contemporary graffiti acted as a futurist weapon against similar oppression, and he felt called-upon to create letters as weaponised symbols, attacking all systems of lexicon control. Interpreting Rammellzee will always prove a delightful challenge, but the idea, seemingly, was to break the chains of formalised language through the animation of graffiti. Viewing the few photographs extant of Rammellzee’s art across the side of trains from the early 80s – an incredibly significant moment of public art made mobile – one can see his sentient alphabet as it shoots arrows and grenades, at war with the enemy of liberation. To Rammellzee’s eye, this was truly the “wild style”, an inside descriptor for NYC graffiti art at the turn of the decade.

Typical of his resistance to definition, Rammellzee’s birth name remains a secret; even his younger brother declines to divulge it in a new oral history and monograph, Racing for Thunder, published by Rizzoli. After using the tags Maestro, Hyte, Risk and Evol Griller in the late 70s, he would officially change his birth name to The Ramm:Ell:Zee, referring to this identity as an “equation”.

Relocating to NYC’s East Village in the early 1980s would be a key development for Rammellzee. A post-Beat, post-punk, pro-diversity environment embraced the artist’s experimental linguistic concepts, recognising them in the same light as those of jazz composer Sun Ra and novelist William Burroughs. My band, Sonic Youth, shared a rehearsal space with a punk-funk ensemble named Konk in the East Village. Konk’s percussionist, Al Diaz (who was along with Jean-Michel Basquiat and Shannon Dawson also a member of the graffiti trio Samo) handed me a copy of a 12in record he had just performed on. Titled Beat Bop, produced by and featuring Basquiat (his art gracing the cover) it would be the first recorded music to feature Rammellzee as he freestyled along with a 15-year-old rapper named K-Rob. The track was relentless. Rammellzee’s lyrics moved through spontaneous surrealism augmented by a shifting reverb: funky psychedelia driven by Diaz’s percussion and Basquiat’s drum machine. This barely distributed recording would be exponentially influential to future rap artists such as Cypress Hill, Beastie Boys and El-P.

My only other experience witnessing Rammellzee in action was hearing him MC a Rock Steady Crew breakdance event in Soho, NYC, and seeing him in the 1983 hip-hop movie Wild Style: he appeared dressed down in a muted overcoat, oddly clutching a rifle, and, unlike many rappers in those days, eschewing any attempt at glitz. He nonchalantly spat out an unbroken stream of improvised poetry, his demeanour both hectic and chill; his words and flow a slurry, almost as if he were reciting glossolalia.

Aside from CBGB, Mudd Club and Tier 3 it was midtown’s Squat theatre where hip-hop and post-punk, funk and jazz truly merged in the early 80s NYC – the no-wave discord of DNA; the drop-dead minimalism of Bush Tetras; the harmolodic guitar shred of James “Blood” Ulmer – iconoclasts all. Rammellzee was an electric presence in this space, and would continue throughout his lifetime to create astounding paintings and sculptures, appearing in startling anthropomorphic monster costumes of his own design. Yet he was far more than just another iconoclast on this scene. With typical individualism he saw himself to be fully engaged in what he termed “ikonoklast panzerism” – weaponising our alphabet to destroy symbols of hate. We were lucky to have him in our corner.

Source: theguardian.com