I

In a video illegally recorded in the 1990s, a group of Pakistani men in traditional shalwar kameez garments are captivated as they listen to the powerful voice of Zarsanga, a famous Pashtun folk musician from Pakistan.

For over fifty years, the uneducated village girl who transformed into the beloved “nightingale of Peshawar” has sung traditional songs about yearning lovers turning to dust, ancient Pashtun tribes and their deep respect for their homeland, traditional jewelry adorning the necks of Pashtun women, and leaving behind darkness. With a scarf covering her emotionless face, Zarsanga appears almost saint-like. Her voice has been known to cause frenzy in some audience members, who break into a version of the Attan, a graceful circular dance believed to have been used by Pashtun warriors to intimidate Alexander the Great’s soldiers.

“I am grateful to God for my voice,” states the graceful 77-year-old, who I encounter on the outskirts of Kohat, a city located approximately an hour’s drive away from Peshawar. “While some people shed tears, others shower me with rupees.”

For many years, Zarsanga’s voice was heard everywhere in Pakistan. However, with the decline of cassettes and DVDs and the rise of new music genres, her music was viewed as a remnant of a bygone era. In 2018, she regained her audience with a modern version of her classic song “Rasha Mama” on Coke Studio, a Pakistani music TV show sponsored by Coca-Cola. This rendition received over 10 million views on YouTube. In 2021, Zarsanga was featured on Malala Yousafzai’s Desert Island Discs and was also selected as one of the recipients of the prestigious Aga Khan Award for Music in 2022. Along with 15 other winners, she shared a prize of $500,000.

However, for over ten years, this well-known vocalist has been forced to lead a nomadic and unstable existence due to being displaced by a flood in 2010. “I have been singing since I was a child, but I still have not received any land from Pakistan,” she expresses with bitterness. “I don’t understand why.” Although the local authorities deny this, one of the most talented folk artists in South Asia is now living in a mud house with a tent serving as a roof.

Zarsanga was born around 1946 in the Lakki Marwat district of north-west Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, now Pakistan. While working as a shepherd, she sang the Pashto folk songs of the late Kishwar Sultan and Gulnar Begum to her first audience: her father’s sheep and horses.

Zarsanga’s father was hesitant when he first learned of her musical abilities that she had honed in the lush fields and forests of Lakki Marwat. Despite the high regard for folk music in Pashtun culture, musicians themselves are sometimes held in low esteem. However, after listening to her, he gave his blessing and encouraged her to pursue her passion for music.

At a nearby wedding, he invited Zarsanga, who was 20 years old, to sing. There, she happened to meet a musician from the area who then arranged for her to audition in front of the famous singer Gulnar Begum. Gulnar had lent her voice to many Pashto films. Zarsanga remembers that the cassette tape ripped during the recording, but they managed to finish it and she soon began performing on the radio all over the country.

She has made significant contributions to the rich folk culture of the Pashtuns, the largest ethnic minority in Pakistan primarily residing in the north-western region. Due to a history of colonial biases that depicted them as a warlike people, the Pashtuns have become closely associated with terrorism, violence, and political unrest, largely due to events in the last two decades. These include the 2012 shooting of Yousafzai, the rise of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement advocating for the rights of Pashtun people, and the Taliban’s recent takeover of Afghanistan. This resurgence of the Taliban has also affected the north-western region of Pakistan, which is home to many ethnic Pashtuns.

According to Scottish writer and historian William Dalrymple, contemporary perspectives on history are limited. He believes that some of the greatest miniature paintings and sophisticated philosophies, such as Islamic art, have originated from Pashtun lands. These include Gandhara art, Timurid paintings, and intricate tile work found in Herat’s towers and Kabul’s bazaars, which have unfortunately been forgotten. Before the partition of India in 1947, the Pashtuns were known as advocates for peace in the region. Dalrymple mentions Abdul Ghaffar Khan, a Pashtun leader who led a large non-violent army and fought against colonialism.

According to Rashid Ahmad Khan, a musician who obtained the first PhD in Pashtun folk music at the University of Peshawar in 2022, there were numerous singers similar to Zarsanga around a century ago. However, in contemporary Pashtun music, the traditional tone has disappeared, except in remote areas of the north-west where folk music styles remain preserved.

Zarsanga, along with her deceased husband Mullah Jan, drew inspiration from a rich oral tradition of lyrics and melodies originating from tappa and landay poems – the oldest form of Pashto folk literature. Despite being illiterate, Zarsanga committed these poems to memory and relied on them during rehearsals. She explains, “We were uneducated, I couldn’t comprehend. I could only sing once I had fully memorized the lyrics.” It is a challenge to determine the exact origins of these ancient lyrics, as they are considered to be a shared heritage among the Pashtun community.

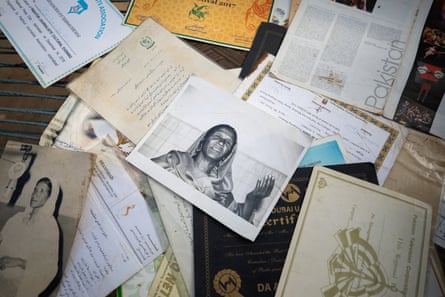

Zarsanga has passed down her musical talent to future generations and is currently revered as a national treasure in Pakistan. In addition to receiving the prestigious Aga Khan award, she has also been honored with the President’s Pride of Performance prize and has been featured in the anthem of the Peshawar Zalmi cricket team. Despite her fame, Zarsanga and her family still reside in a few rented mud houses.

Display the image in full screen mode.

In 2010, a series of destructive floods caused over 12 million people in Pakistan, including Zarsanga and her family, to be displaced. They were forced to live in tents on the side of the road after their homes in Azakhel, located in the north-western district of Nowshera, were demolished. In 2017, Zarsanga was compelled to flee her town when she was assaulted by a group of people due to a financial disagreement between her sons and their neighbors.

Pakistan is facing high inflation rates and the aftermath of devastating floods in 2023. As a result, a septuagenarian is now the sole financial support for her entire family. Despite sending multiple applications and making videos, Zarsanga has not received any financial assistance from the government. However, Rashid Ahmad Khan, the president of Hunari Tolana (a Pashto literary and cultural organization), claims that Zarsanga and her family have received a total of three to four million Pakistani rupees (equivalent to £8,500 and £11,200) from the Aga Khan prize fund and the Pakistani government over the years.

Despite the uncertain living conditions, Zarsanga’s popularity remains strong, even reaching Afghanistan where 40% of the population is made up of Pashtuns. However, due to Taliban’s strict interpretation of Islam, music is now prohibited, but individuals like Fatima Faizi, an Afghan journalist who sought refuge in the US, continue to support and admire Zarsanga. According to Faizi, Zarsanga’s music was a staple in her household and she and her cousin would often dance to it. Zarsanga herself is modest when discussing her own achievements but is fervent in expressing her love for the Pashtun diaspora, especially those living in England, London, America, and Germany. She promises to always sing for them whenever they desire it.

In 2018, Zarsanga’s performance on Coke Studio introduced her to a new audience around the world. The performance featured her singing a traditional song, “Rasha Mama,” accompanied by Pakistani folk band Khumariyaan playing the rubab and guitar. The song then transitions to modern electric guitar riffs and the soft vocals of pop singer Panra. The producers of the session, Zohaib Kazi and Ali Hamza, see this as Zarsanga’s way of passing the torch to the younger generation of artists.

Display the image in full screen mode.

The duo aimed to bring attention to regional languages and music that were neglected during the upheaval following India’s partition in 1947, when Urdu became the dominant language. According to Hamza, the urban environment and customs after partition were primarily influenced by economic opportunities and the desire to impress colonizers. Kazi explains that their travels throughout the country revealed the lack of representation for many aspects of Pakistani culture in mainstream media, which is where Zarsanga became important.

Over the past five decades, the majority of well-known Pashtun folk singers have been women, such as Zarsanga, Sultan, Begum, and the late Qamar Gula from Afghanistan. These women are highly respected in a traditional and male-dominated Pashtun society where women are not typically seen in public roles. According to Kazi, Zarsanga was a rare exception to this norm and served as a symbol of rebellion as both a woman and a Pashtun singer. The enduring relevance of her career is a testament to her strong spirit.

However, due to the patriarchal culture and negative attitudes towards folk musicians in Pakistan, none of Zarsanga’s daughters have pursued music. She explains, “No one in my family, particularly the women, sang before me,” and it is uncertain if there will be another female musician in the family.

Source: theguardian.com