If you want to buy a bespoke, brand-new machine to cut your own vinyl records at home, there seems to be just one man who can help you. Ulrich Sourisseau’s workshop is in a disused railway station in a remote part of the Black Forest in Germany, and he is in extremely high demand. He’s selective about who he sells his machines to, and if he does agree to make you a bit of kit, he’s a little old-school. “He’s cash-only, so I had to travel there with €7,000 on me,” recalls Jon Downing, who bought one back in 2017.

Downing then began running his own micro record label in Sheffield, Do It Thissen (that’s “do it yourself” in Yorkshire dialect), specialising in music from his home region. It was a retirement project “to keep me out of mischief and give something back to the local scene,” he says, but Downing has since put out 75 records, from the wonky weirdo punk of Dearthworms to the psychedelic krautpop of Sister Wives, which he personally cut in his shed at the bottom of the garden.

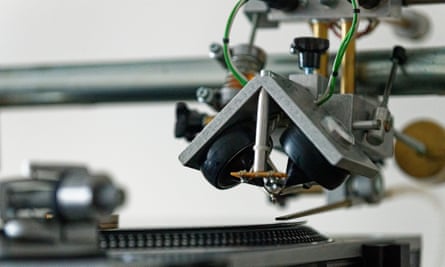

The lathe-cutting machine he picked up in Germany produces records one at a time using a diamond needle. They are cut in real time on to blank vinyl discs from a digital source. And this service, and the record labels using it, are booming. “When I wrote our business plan seven years ago I did loads of research and I found maybe two or three other lathe-cutting services,” says Tasha Trigger, who co-runs Lathe to the Grave. “And now they’re 10 a penny.”

The enigmatic Sourisseau in Germany may be the only place to buy a freshly minted machine, but with more people refurbishing and selling older models, records are becoming more readily affordable in small batches from an increasing number of sources. “No project is too small for us,” Trigger says. This means that people are getting even the most niche things put on to record now, using them as gifts, mementos, or preserving family memories by pressing them into grooves. “We’ve done one-off records of everything from a baby’s first words pressed to vinyl, to a gender-reveal one where they got their doctor to send us an email with the gender of the baby, as they had a choice of two songs for boy and girl.”

As well as serving smaller record labels, many lathe-cutters also sell direct to artists, who cannot afford to go to a large pressing plant that requires a minimum order. “Not everybody can afford 300 copies,” Trigger says. “So if we sell somebody 20 records, and they can sell them all on tour and make their money back, while getting coverage, then that’s our job done. Then they’re not going to sit around with 200 spare copies holding up their bed.”

Graham Duff, known for writing TV shows such as Ideal, starring Johnny Vegas, also curates his own label, Heaven’s Lathe, in collaboration with lathe cutters Bladud Files! It allows him all the fun and creativity of running a record label but without the stress, risk or workload that would usually go with it. They only cut 100 copies each of the records they release, which have included music by Wire’s Graham Lewis, Throbbing Gristle’s Cosey Fanni Tutti, and even one of Lee “Scratch” Perry’s final recordings.

“For all of us involved it’s a side project,” Duff says. “But it’s something precious. You can make a really high quality product, but you’re not having to have a massive outlay. And lead times are much shorter – you could be waiting a year at bigger manufacturing plants, so this creates a much shorter route from having an idea to recording it and getting it out there.”

It’s a win-win for artists, too, who can release a physical record stripped of the usual expectations and obligations. “There’s no pressure on the artist,” says Duff. “There’s no cost, it’s completely up to them what they want to release, and they retain all rights.” He gives the example of Adi Newton from electronic experimentalists Clock DVA, who lathe-cut a piece of piano music. “You’re opening up channels for people to explore.”

Demand is growing. Trigger is in talks with Sourisseau about acquiring a third machine so they can increase production next year – they currently run two machines for 70 hours a week – and it has enabled her and her partner to quit their other jobs. “It’s been incredible for us to be able to do this full-time,” she says. “But ultimately, we want artists to support themselves and know that there are other options out there: it’s not just streaming or nothing.”

Source: theguardian.com