I

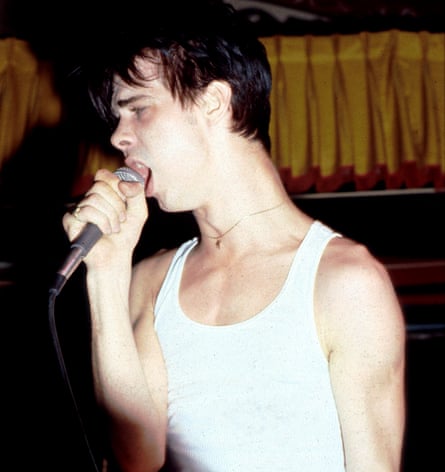

In 1981, a group is filming a music video at a landfill on the outskirts of Melbourne. Their concept is to depict hell through a cartoon figure with six limbs. The video features a young and thin Nick Cave, described as a “chubby bug,” performing a pole dance in a circus tent. The song being played is titled “Nick the Stripper” and explores themes of self-hatred.

The Birthday Party is behind him, swaying and stumbling. The band, previously known as the Boys Next Door, has come back to their hometown after a year in London. They have transformed into a much darker and intimidating group to record their debut album, Prayers on Fire. The melody, if one could call it that, relies on a haunting three-note riff from guitarist Rowland S Howard.

The activity shifts to the area outside of the tent. The band has brought along residents from a mental health facility, and one of them is standing on a gallows. Cave is dressed in a loincloth. A troubling scene with a goat takes place.

A recently released film about the band Mutiny in Heaven showcases their unique style and energy for the entire four minutes. Director Ian White believes it would be a waste not to include the entire piece, as it perfectly captures the band during a crucial point in their development.

It’s half a world and two generations removed from the Nick Cave of today, who dispenses weekly words of comfort, wisdom and occasional humour via his newsletter the Red Hand Files. But the Birthday Party, the point band of the post-punk scene that coalesced around the famed Crystal Ballroom in St Kilda at the turn of the 80s, was where it all began.

During this period, White had observed the band at its most terrifying peak. “Even four decades later, those performances still hold significance for me,” he recalls. “They were probably among the few shows I’ve witnessed that had such a profound effect.” According to White, part of this impact was due to the tangible feeling of peril surrounding the band, although he admits to being more concerned for their well-being than his own.

The anxiety was valid. Howard and Cave, who both struggled with a heroin addiction for many years, died from liver cancer at the age of 50 in 2009. Howard had recently finished his last album, Pop Crimes, which featured a disturbing image of him on the cover as he neared death. The bassist, Tracy Pew, passed away before reaching 30 due to head injuries from an epileptic seizure in 1986.

Mick Harvey, who was also a guitarist in the Birthday Party alongside Howard, remained a multi-instrumentalist for Cave in the Bad Seeds for 25 years. When asked how he managed to maintain his sanity during this time, Harvey simply credits staying sober and handling the situation as it came.

He explains from his residence in Melbourne that their actions as children, outside of school, were similar to what they are doing now. It is widely recognized that many men do not mature or leave behind teenage habits until around the age of 25, and even then it may be a stretch. The group had already ended before any of them reached 25.

Phill Calvert, the drummer, recalls his youth as more of an adventure, though not necessarily a spectacular one. He shares, “During our first year in England, we were barely getting by and struggling with harsh weather and hunger. It wasn’t enjoyable at all.” However, he believes that experience prepared the band for their future and without it, they might have remained in Australia and ultimately lost momentum.

Unfortunately, the Birthday Party was not meant to have longevity. They only released one more album, Junkyard, before Calvert was unexpectedly fired in late 1982. However, Calvert holds no resentment towards the situation. He acknowledges that after his departure, another member was chosen to take the blame, ultimately leading to the band’s demise.

The majority of the film centers around conversations with Howard. During one moment, he reflects on watching the Doors play at the Hollywood Bowl, where law enforcement kept Jim Morrison separated from the audience. This moment, to Howard, exemplifies the essence of rock music – possessing enough intensity to require a barrier between the band and the crowd.

It was a challenge to capture Pew. The bassist played a crucial role in the sound of the Birthday Party – his uneven basslines inspired many US noise-rock bands, including Sonic Youth, Big Black, and the Jesus Lizard. His appearance was also unique: a mustachioed cowboy in leather pants, wearing a string vest and a Stetson, resembling a goth version of a village person.

Pew centred the paradox at the heart of the Birthday Party. “The band were enigmatic, because they were such an odd contradiction of different things – intelligent and literary, yet visceral and brutal,” White says. “Seeing them when they were bored or in a bad mood was as good as seeing them at the peak of their game.”

Unfortunately, Pew did not survive to share his story and only pieces of it remained. His most well-known statement was that rock music, if it were to be remembered at all, would be seen as the lowest point of culture. White explains, “The audio we had of Tracy speaking, whether he was telling a story or being condescending to the interviewer, was difficult to incorporate into the context.”

The filmmaker primarily used historical materials to create his movie. The goal was to immerse the audience in a bygone era. The film does not feature interviews with people: “Sorry, Henry,” Harvey laughs, mentioning Rollins who has appeared in numerous music documentaries. There are short audio clips from Thurston Moore and Lydia Lunch.

According to White, the quality of the material speaks for itself and does not require external validation. Therefore, the focus is on showcasing dynamic live footage with minimal interruptions. White explains that there are no catchy elements to rely on, so the audience must listen closely. The emphasis is on less talking and more music.

Cave is currently touring in the United States, where he has recently started performing the song “Shivers,” written by Howard and originally sung by the Boys Next Door. This is a surprising change, as Cave had previously distanced himself from the song for many years. Harvey, his former bandmate, couldn’t resist taking a jab at him. He expresses frustration, saying, “It’s easy to make grand gestures now from a safe distance. But where were you 14 years ago?”

The duo had a falling out when Harvey left the Bad Seeds, but they have since mostly made amends. Harvey states, “We have resolved our differences.” He publicly apologized to me, although he has never directly addressed me. That’s just his way.

He smiles. “He has something to say to me, that jerk!”

Source: theguardian.com