It is difficult to think of anyone who has become as famous as Marianne Faithfull after having achieved so little. Fifteen years ago she recorded As Tears Go By, the first of her string of breathy, insubstantial pop hits, but even at her most successful she was never taken seriously – more as a curiosity, Jagger’s pretty girlfriend with the posh voice, and then the convent girl turned junkie.

She emerged from all that to prove, if briefly, that she could also be an accomplished actor. Then she returned to mediocrity, both in her singing and acting, making dreadful albums like Faithless and occasionally appearing in shows where it seemed she was being used more for her name than her ability. She had a runaway No 1 hit in Ireland – with a country song, surprisingly – but apart from that, she’s done nothing of interest for a very long time.

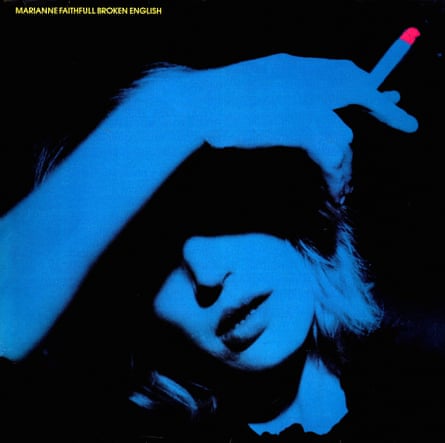

On Friday, all of that is going to be changed, with the release of Broken English (Island M1), a new Marianne Faithfull album that is actually very good indeed but will be controversial for all the wrong reasons – there’s one song on it by Heathcote Williams that upset EMI so much that they refused to press or distribute the record, as they normally do for all Island products. Happily, Island has made other arrangements for bringing it out, as this album finally proves that Marianne can write, and sing (this time with a compelling, cracked voice) with enough flair and invention to set her in the British contemporary vanguard.

If I’m surprised, the artist herself acted as if this U-turn was quite predictable. “To be frank, I always knew I was something quite extraordinary,” she said in that quite extraordinary posh voice that has survived so much. “It was as if I had a lot of potential but would never fulfil it. I blew it on purpose or had no confidence.”

I had last met Ms Faithfull 17 years ago when I was at school in Reading, she was at the convent down the road, and we both sang in the school opera (I’ve still got the album, one of the lesser known gems from the early sixties). This time she suggested we met at the Ritz, from where we were immediately expelled because neither I nor the press officer from her record company was wearing a tie.

She looked quite as delightful as I remembered her, and managed to cheer me and depress me with her first gushing sentence “Robin, I’ve been following your career with interest. It was in Brighton I knew you, wasn’t it?” We tumbled into another smart bar down the road. She had very bad tooth-ache and it needed calming.

The setting seemed somewhat bizarre for discussing the latest, very welcome turn in her career – bizarre because she chose such a plush lounge in which to describe the hard times she’s been through. Until a year and a half ago she was paid a regular £100 a week by the company originally started by Brian Epstein. She didn’t like what they were doing (“it’s a laundry service, a disaster, it’s not important, I don’t want to talk about it or think about it”) and she walked out.

Then “through hunger and desperation” she started performing, only to find that she was losing money. But in the process she met a new series of musicians, and started performing worthwhile material for the first time ever. Musically, she has been influenced by the punk aftermath (she is now married to former Vibrator Ben Brierley). But the main force on her album would seem to be Steve York, that under-recognised bass player who used to back Elkie Brooks and whose range stretches far beyond the new wave. He’s given Broken English its distinctive character – a restrained but powerful, pared-down sound against which Marianne declaims or acts out a surprising selection of songs. There are three on which she has written the lyrics herself – including a folky piece about witches and the title track, which is a simple bemused questioning of Ulrike Meinhof. Then there are standards. These include John Lennon’s Working Class Hero (“just because I’ve always wanted to do it”), and, also released as a single, Shel Silverstein’s Lucy Jordan (“about a mad housewife – a story, so I can act it.”).

Then there’s the track that caused all the trouble, Williams’ Why D’Ya Do It? – which has now been moved from opening cut to final song on the album. It contains a variety of shocking words that are in constant everyday use, and, as she put it “it’s about sexual jealousy – all the song does is crystalise the sort of row people are having all the time putting it down in exactly the way they’d talk.” As a cameo of well-observed female fury it’s certainly very effective.

Marianne herself is very pleased with that track “because it’s the first angry statement I’ve made. In all the good things I’ve done I’ve always played a victim and pretended to be very sweet. But in the past I did what people told me – I tried to suss out what they wanted and gave it to them. I did this record for myself.” She wants to give some concerts to promote the record, but Island Records won’t let her. “They think I should play somewhere grand, or not play at all. Perhaps it’s mystique, or perhaps they think I’ll fall over … Instead, an expensive promotional video package is being assembled by Jubilee director Derek Jarman, and that will be shown on television and as a cinema short.

Maybe it was the effect of her toothache cure, but her mood was wavering between boundless, confident optimism and extreme nervousness. “Am I very paranoid? Oh yeah – can’t you sense that? Why? Because of everything that has happened – it’s taken me ten years to really get back into the business. It wasn’t getting ripped off that matters, it was just that I never got an opportunity to do anything any good or work with people any good. They saw me as something they might be able to make a bit of money on, but never as anyone who had anything to say.

“I felt terribly manufactured, and I was. There was probably something real they could have done, instead of the most obvious, with As Tears Go By. But I was only 17.” She suddenly found the whole period very hard to talk about. “I don’t understand it, so please don’t ask me – or rather you tell me. Perhaps I’ll find something out from what you write.” She found it even harder to talk about coping with the image of Marianne Faithfull. “It does terrify me, always, though I try not to think about it … you know I was scared to do this interview and I’m getting myself into a state. I know what you’re going to ask and don’t know what to say …” She then voluntarily changed the subject to her drug days. “I must have given up then or I wouldn’t have got into heroin. It’s like wanting to kill yourself but I didn’t manage to. I realised that I couldn’t get out of it that easily. And if I didn’t do anything good my life would have been nothing to me. So I got myself back.”

At the end of all that, what actually matters is that she’s made an excellent album and her ambition has helped her survive an uneasy 15 years. She said she lived “a secluded life these days,” but her ambition remains as big as ever. So her aim now is to be “something real, not too arty or serious, but real like BB King, Ma Rainey or Billie Holliday – except they are great. But something definite will happen. I may become a great star, which will be great. It’s what I want to be and what I think I am.”

Source: theguardian.com