O

On the evening of January 13, 1966, the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry held their yearly dinner at a Park Avenue hotel. The dinner menu included string beans, roast beef, and baby potatoes. The entertainment for the night was unconventional – a local artist named Andy Warhol had been invited to speak, but instead, he put on a multimedia performance with his band, The Velvet Underground and Nico. They played loud and provocative songs such as “Heroin” and “Venus in Furs” while 300 medical professionals and their spouses watched in their formal attire. One doctor described the event as a “spontaneous eruption of the id,” while another compared it to an escape from a prison ward.

That wasn’t totally wide of the mark; Edie Sedgwick, the Warhol “superstar” writhing on stage had once been institutionalised by her wealthy parents (while in hospital she met Barbara Rubin, another scenester who filmed part of the evening). And the band’s linchpin and songwriter Lou Reed had, in his late teens, been given electroconvulsive therapy to treat suspected schizophrenia (he claimed later it had been to “discourage homosexual feelings”).

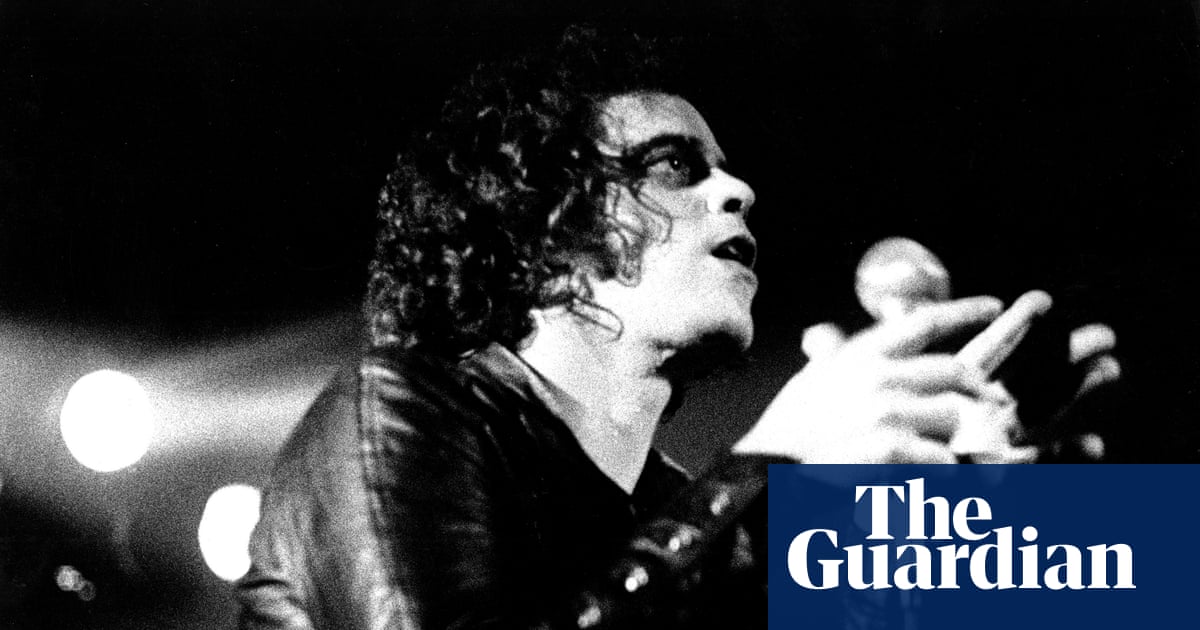

The event itself was in the style of Warhol, seeking attention in a bratty manner. Some participants were able to act out a fantasy of revenge against their psychiatric oppressors. However, the significance of the event goes beyond that. The Velvet Underground was not just a shocking art gimmick for shock value. It served as a platform for Reed’s talents as a musician and lyricist. Just three months later, the band would record one of the greatest love songs of the 1960s, “I’ll Be Your Mirror”. This marked the beginning of Reed’s career as a world-renowned figure representing the dark aspects of human nature such as addiction, desperation, and excess.

David Bowie, a devoted fan of the Velvet Underground, bestowed upon him the moniker “King of New York.” Bowie played a crucial role in revitalizing Reed’s solo career with the production of Transformer, which featured his most successful single, Walk on the Wild Side. Will Hermes has written a meticulously detailed and vibrant new biography, titled “King of New York,” which is the first to utilize the archive donated by Reed’s widow Laurie Anderson to the New York Public Library. Similar to his previous book, “Love Goes to Buildings on Fire,” which focuses on New York’s music scene in the mid-70s, Hermes skillfully paints a portrait of Reed’s various environments and relationships, including a diverse group of collaborators, friends, and romantic partners.

It seems as though he is modernizing Reed’s work for a new era, specifically as a visionary for the liberation of the LGBTQ+ community and gender nonconformity. This isn’t far-fetched, as one of his most notable songs, “Candy Says” from 1969, beautifully captures the struggles of gender dysphoria. In 1972’s “Make Up,” just three years after the Stonewall riots, he boldly declared, “Now we’re coming out, out of our closets / Out on the streets.” From 1974 to 1977, his partner was Rachel Humphreys, a transgender woman, and they were unapologetically open about their relationship. However, at times it does feel forced, as if Hermes is trying too hard to earn recognition as a progressive rock icon. Can we really consider his famously unlistenable album of guitar feedback, “Metal Machine Music,” a “radical queer art statement” that silences homophobic criticism? That’s up for interpretation.

Reed is a complex and awkward figure, revered as an idol. As Hermes follows his journey from suburban Long Island to the avant garde scene downtown, with stops at Syracuse University and under the guidance of poet Delmore Schwartz, he also observes the exacerbation of Reed’s emotional wounds and flaws. The other musical genius of the Velvet Underground, John Cale, believed that Reed’s often shocking behavior stemmed from his fears about his own sanity. This led him to intentionally provoke others in order to feel in control, rather than living with uncertainty or paranoia. He constantly sought to gain an advantage for himself by bringing out the worst in people.

The writer describes how Lou Reed’s insecurity drove him to be a successful poet and prove his worth to others, but also caused him to be selfish and even violent. His first wife, Bettye Kronstad, shares that being in a relationship with Reed meant being treated with both respect and abuse. Reed’s song “Perfect Day” was inspired by a date with Kronstad and is accurately described as portraying a scene of self-loathing. His bandmates also experienced his difficult personality and many collaborations did not last long. This reputation was later parodied by the Onion in an article about Reed’s transplant due to worsening hepatitis. The piece humorously quotes the new liver as saying it is hard to get along with Reed due to his unpredictable behavior.

The use of drugs without a doctor’s supervision was likely unavoidable given the circumstances, and Hermes recounts some alarming instances of this. Although Reed was known for his song “Heroin,” he was more consistently addicted to amphetamines, partly because they were easy to obtain from medical professionals and weight loss clinics, and partly because they initially boosted productivity – until they didn’t. Nevertheless, the fear and decline caused by his addiction directly influenced his writing. As he stated, his “main idea” was “to take rock & roll, the popular format, and make it more mature with adult subject matter.” This is evident in songs like the painful withdrawal anthem “Waves of Fear,” the haunting string ostinato in “Street Hassle” which tells the tragic tale of an overdose, and, of course, “Heroin” itself. Eventually, Reed sought help and attended Narcotics Anonymous meetings. At one meeting in New York, as Hermes reports, he was confronted by an addict who shouted, “How dare you be here – you’re the reason I started using heroin!”

Despite a lack of initial commercial and critical success, Reed was able to have an influential impact on others. The story of the Velvet Underground largely revolves around their influence after their breakup, as Hermes notes in his list of artists who were inspired by them. From Patti Smith to Talking Heads to Blondie, many artists looked up to Reed as he played at CBGBs just a few years later. This quick rise to legendary status is a common theme in the music industry, but Reed and the Velvets were fortunate enough to experience it themselves. (Even this legendary status is subject to myths and legends, such as the famous quote attributed to Brian Eno about the band’s first album.)

Instead of simply observing, Reed’s reputation flourished over time, similar to a frog slowly cooking in a pot. Through the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond, Hermes meticulously recounts the production of his albums. As he received payments for the use of his older songs in samples and advertisements, Reed became a wealthy individual. His most notable release in his later years, New York, boldly examines his hometown, condemning poverty and discrimination and satirizing a optimistic poem about the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses, I’ll urinate on them.”

However, if he gained recognition as the poet of the dark side of rock, whether it be his own or the society’s, it was to promote a more honest form of beauty. In the last chapter and epilogue, Hermes recounts Reed’s last moments in 2013 – his body had rejected the transplanted liver and he was aware of his impending death. He expressed, “I am extremely vulnerable to beauty at this moment,” while his friends serenaded him with songs from the Shangri-Las, Nina Simone, Frank Ocean, and Radiohead as he floated in his warm pool. In reality, he always had been.

Source: theguardian.com