We’re two Black men who have been attending camping festivals the entirety of our adult lives – but Glastonbury, arguably the mother of festivals, had never been on either of our radars.

Can you blame us? The artists that tend to headline certainly weren’t what our parents played growing up. Watching the BBC feed from the Pyramid stage showing tens of thousands of similarly reddened faces, the crowd seemed so white to us; and then there is the mud, drugs and unavoidable discomfort central to country life, none of which are usually celebrated in Black culture. But Glastonbury has done more than many other big UK festivals to embrace and promote Black and Brown music, and Black art runs through the festival’s DNA.

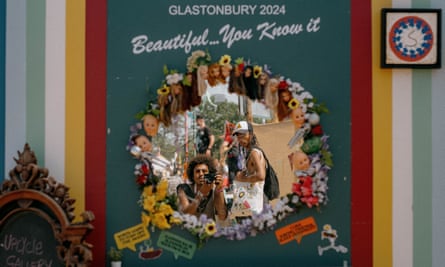

So. The car is packed, rum decanted, and we’re setting off to Somerset. We’re going to find the Black people, and we want to know how they do Glasto.

The narrow demographic is immediately stark, and walking around as a pair makes us realise just how narrow it is. Eyes, curious but not hostile, wander our way as we stroll. In the interstage area a slightly drunk white lady approaches, “I love your hair,” she says to Ollie, regarding his afro. “Mine will be like that by the end of the weekend!” Microaggression aside, Ollie has left his afro pick in the car, so she has no clue about the rat’s nest awaiting him on Sunday. Big mistake. The only comb available here is eight feet tall and functioning as a chair. Useless.

We bump into Michael from Kenya, who tells us he’s excited to see his favourite artist, Dua Lipa. “I named my niece after her,” he says, after falling in love with her music while studying accounting.

As we walk into the staff bar at the Silver Hayes area we lock eyes with Muti. He and his friend Blaise are sitting, soaking in the sun. The guys want Black people to go outside, to reclaim the land. They want the Black network forming here to flourish into a national festival community. We want to find each other; as Blaise says, it’s an unwritten rule. Long live the linkup.

We grab a beer before meeting Alice, who works in production. She is working eight festivals this summer but this is her first Glastonbury. “It’s an intense lifestyle,” she says, but adds that once you’re in, it’s easy to keep being asked back: “Just don’t be a dick.”

Some canny texting gets us backstage with Hak Baker, sitting on a red leather banquette with zebra print cushions: a curious contrast with Hak, who is calm and sincere. It’s his fourth year, and he considers each performance a statement. We ask him about the sense of community his music brings: “To be able to do it on a bigger scale and bring people together, that’s my job,” he says. Hak recognises the power of the Glastonbury stage, and there’s a harmoniousness here that he doesn’t take for granted. “I feel like [Glastonbury] exalts what the great things about being British are, there are no bad vibes here … it’s like you’re on an island separate from England.”

Before we know it, we find ourselves in the cacophony that is Shangri-La, an immersive array of satirical art installations in the festival’s south-east corner. Out of nowhere comes Mr Glitch, a security guard (or rather self-described “overseer”) making sure “the vibes stay correct”. He’s dreamed of coming to Glastonbury ever since seeing Jay-Z perform on TV in 2008. “This is the biggest event in the UK,” he says. His smile is huge.

He reveals his real passion: DJing. “This is the place for opportunities, if you know how to network.” He’s not wrong: there is something levelling about this cross-section of people – farmers, ravers, Paul Mescal – all camped out in a field together. And after some sweet-talking, he manages to line himself up a set in the Park area during one of his breaks.

Moya Lothian-McLean lends us her journalist’s eye. In her observation, although the programming has become more diverse, the crowd has yet to catch up. (This likely explains the relatively small crowd at SZA’s headline set, despite the artist being more than popular enough to fill that spot on the lineup.) She points out that only urban festivals really sell themselves to Black people. “The traditional camping festivals, they’re not marketed in the same way.” We agree about the complexity of the relationship between British people and the countryside; Moya grew up in the country, so she’s acutely aware of subtle cultural norms of Englishness and the ways in which Black people are made to feel unentitled to rural space. And that’s before mentioning the cost. “Give some free tickets out,” is Moya’s suggestion.

We chat to David at Maceo’s, the crew bar where he works, in Block9, Glastonbury’s queer hub. He seems effortlessly relaxed, and we ask him if he’s found his niche. “Definitely,” he says. He’s a proponent of people of colour coming here to work: “Giving people opportunities to build their own spaces is probably the best way of doing it.”

Nia Archives is shining from tooth to toe when we chat at Silver Hayes. There’s a sisterhood of Black female DJs this year and she’s excited to catch sets from Sherelle and DJ Flight. We ask Nia if there’s anything particular to the Black northern experience of Glastonbury. “It’s a very different experience being Black up north,” she says. “It’s not as mixed.” So she’s excited for the blending that happens here; “Glastonbury is a place where I feel really at home.” Nia says she’d love it if more young Black people took up space here, and echoes our feeling that what you see from home isn’t necessarily what you’ll find when you arrive.

Chris and Kwame represent the backstage heart and lungs that keep Glastonbury marching along. Amid flapping doors and sweating production assistants they sit sagely. Chris has been running the Shangri-La district of the festival for 39 years, and Kwame has been coming as a performer and now manager since the early 90s. Glastonbury is one of the only major festivals still flying free from the claws of corporate sponsorship, and this matters. “There’s an anthropological thing going on here,” Chris says; the festival runs on the time and energy of volunteers. But don’t mistake this for utopia – Chris has seen decades go by with senior festival production devoid of Brown faces, so he’s helped start a course called Festival Lab, and placed aspiring Black event producers around the country. Chris is finding money to make festival work more affordable and accessible. “I don’t think there’s a big conspiracy,” he says. It’s about effort.

Kwame can see a turning point. We’d noted the shift in programming here and he agrees. He says backstage just needs to catch up. People have got to band together and boot the gate off its posts. That doesn’t happen without help, but help can’t only mean selfless self-organisers like Chris and Kwame.

Overall, we find that people are overwhelmingly kind and welcoming, and bar the odd comment – and the person who approached us to buy drugs – we’ve had the time of our lives. Everyone agrees it’s too expensive, and that there aren’t enough Black people behind the scenes, but we think that can be addressed. Black life is alive and well at Glastonbury, and we’ll definitely be back next year. You should come too.

Source: theguardian.com