I

If not for a tragic mining disaster in Cumbria, music may never have found a place on London’s Denmark Street. On May 11, 1910, around 7:30pm at the Wellington Pit in Whitehaven, a build-up of methane was ignited by a stray spark, possibly caused by a faulty safety lamp. This resulted in an explosion and underground fire that destroyed tunnels and blocked potential escape routes. At the time, 140 men and boys were working in the mine, with only four managing to escape. The fate of the rest remained unknown. Despite one survivor going back into the mine to assist with the rescue efforts, conditions proved too difficult. The King even sent a telegram to the mine owners to express his concern while families anxiously waited for news of their loved ones. According to the Times & Express, it was a night filled with immense human suffering.

The mine remained closed until late September, when 136 bodies were carefully and painfully retrieved from the ground. Among them were a father and his two sons, who were found lying together in a makeshift bed. A message was inscribed on a wooden beam nearby: “God is our safe haven and our source of strength.”

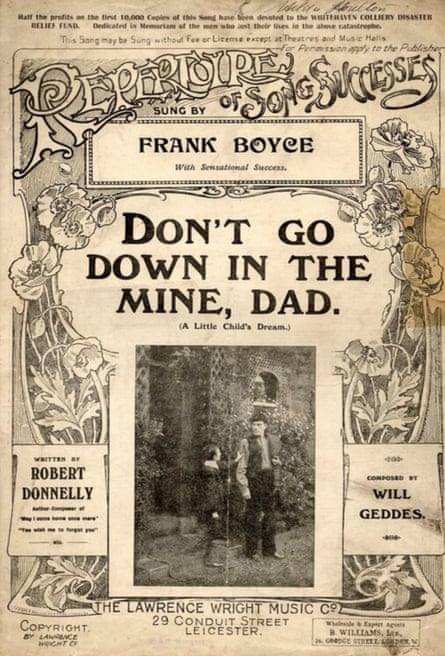

The tragic event captured the attention of the public, and a popular song reflected their sentiments. “Don’t Go Down in the Mine, Dad” was reportedly influenced by a mining accident that occurred in Wales in 1907 and credited to Will Geddes and Robert Donnelly. The song narrates the story of a child who has a dream about a fire in a mine and warns his father, who happens to be a miner, about it. Despite his premonition, the father still goes to work, but at the last minute, he changes his mind and returns home, avoiding the pit fire that kills many of his coworkers. The song gained popularity again after a disaster in Whitehaven and became a hit. The rights to the song were owned by a sheet-music publisher named Lawrence Wright, based in the Midlands, who sold over a million copies of the score. He donated half a penny from each copy to the disaster fund and used the rest to relocate to London.

On a rainy Wednesday morning in 1911, Wright came to Denmark Street. Legend says that he got to St Pancras station and rented a wheelbarrow. He filled it with sheet music, his violin, and a mandolin. Then he pushed it all down Tottenham Court Road to Charing Cross Road, where he turned left onto Denmark Street. There, he paid £1 a week to rent a basement at No 8. This was the start of what would become the most significant street in the British music scene.

The location of Denmark Street was not very luxurious for an office. The area of St Giles still had a negative reputation due to its past as a crime and illness-infested slum. There was also a strong smell of cooked fruit from a nearby Crosse & Blackwell factory, known for producing a variety of pickles, sauces, mustards, and jams. Wright’s music publishing company was not the first on this street, as Francis, Day & Hunter had already established themselves in 1897. They later moved to Charing Cross Road to be closer to the center of London’s book trade and the bustling West End theatre district.

Sheet-music publishing could be an extremely lucrative business. In the absence of gramophones or radio, most homes and just about every pub had a piano around which people would gather; new songs were usually debuted at music halls and those that turned out to be popular with the public were rushed into print in the form of sheet music. A hit – which usually meant one with a memorable chorus and a melody that was easy to master by an amateur pianist – could shift hundreds of thousands of copies.

The publisher held a prestigious position in the emerging music market. They were responsible for discovering songwriters, funding their compositions, and producing and distributing sheet music. The publisher needed a keen ear to identify potential hit songs and secure them at a low cost before competitors could. This model served as the foundation of the London music industry for the next five decades. According to Beatles producer George Martin, having a publisher was crucial for success as they would promote songs to record companies and radio stations, giving them a chance to become popular. Without a publisher, songwriters had little chance of making it in the industry.

Lawrence Wright turned Denmark Street into a British version of New York’s songwriter avenue, Tin Pan Alley. Wright was born in Leicester in 1888, the son of a violinist who sold sheet music and instruments. He went into the family trade, playing and singing songs on an old upright piano out on the street, and selling the sheet music to his audience. He was successful and opened his first shop in 1906 in Leicester, while running four market stalls across the Midlands.

Initially, a large portion of the music that Wright sold originated from the United States. However, he eventually started composing his own songs. Some of his early achievements were with topical songs, such as Long May He Reign/Coronation March which was written for the coronation of George V in 1910. Nevertheless, his breakthrough moment came when he spent £5 to obtain the rights to publish his song Don’t Go Down in the Mine, Dad. Located on Denmark Street, Wright worked tirelessly to promote his music. According to Ian Whitcomb’s 1972 book, After the Ball, Wright was heavily involved in all aspects of his business – from building shelves and furniture to sleeping on a folding couch in the basement and composing the majority of the songs he published.

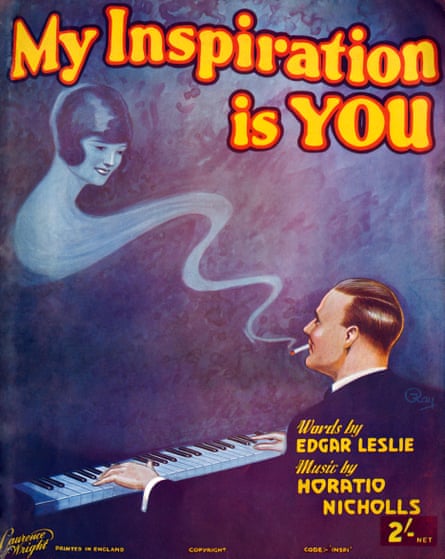

Wright expanded his business from the basement of No 8 to eventually encompass the entire building. However, as his business continued to grow, he found that the space was no longer sufficient. In order to accommodate his expanding empire, he relocated to larger premises at No 19, which he named Wright House. Alongside running his business, Wright also found success as a songwriter under the name Horatio Nicholls. He was known for his ability to write “simple songs for unsophisticated people”, as described by one contemporary. One of his most successful songs was Blue Eyes, which was written in 1915 and sold over a million copies. He later co-wrote That Old Fashioned Mother of Mine, which was supposedly inspired by a conversation he overheard on Tottenham Court Road. This song sold approximately 3 million copies.

One of his greatest accomplishments was the song “Among My Souvenirs,” with lyrics written by Edgar Leslie. The two came up with the song while riding in Wright’s Rolls-Royce on their way to Llandudno. “Among My Souvenirs” is one of the few songs from the prewar era of Tin Pan Alley that is still popular today. It was first a hit for American bandleader Paul Whiteman in 1928, and has since been recorded by Connie Francis, Marty Robbins, Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, and Frank Sinatra. As the author liked to say: “You can’t go wrong with the songs of Wright.”

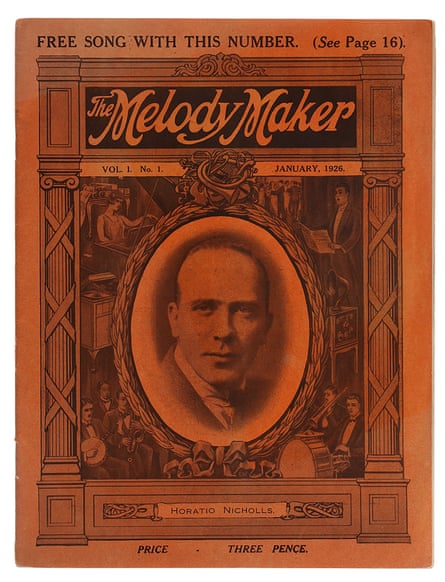

Wright was confident that Among My Souvenirs would be successful, so he purchased the front page of the Daily Mail to advertise it. Eventually, he became dissatisfied with relying on press coverage and decided to create his own newspaper, the Melody Maker, in January 1926. This newspaper primarily focused on promoting Wright’s own music catalog and was published monthly from the basement of No 19. It was edited by drummer and dance-band leader Edgar Jackson. The first issue featured Horatio Nicholls, who was actually Lawrence Wright himself, described as “one of the most talented and popular composers of light music, both in England and around the world”.

Wright retained an interest in Melody Maker right up until his death in May 1964. When writer Chris Welch began working at the paper in the early 1960s, Wright was still alive: “My editor, Jack Hutton, would say he was off to lunch with the ‘GOM of TPA’ – the Grand Old Man of Tin Pan Alley,” says Welch. “He was this father figure and whatever he said or did we had to write about it. Even if we’d rather be writing about the Beatles, we had to cover Lawrence Wright stuff.”

In interviews, Wright, who does not smoke or drink alcohol, is perceived as uninteresting. He once stated, “Alcohol, smoking, and sex are harmful.” He believes that music is the ideal substitute because it communicates a universal language. Even if I speak English to a French or German person, they will not understand, but if I play a piece by Schubert or Irving Berlin, the entire world can relate. However, when it came to selling records, he was willing to do whatever it took. He chartered a plane to fly over Blackpool with Jack Hylton and his band on board, performing a song called Me and Jane in a Plane and dropping sheet music onto the surprised beachgoers below. He also had his employees ride around London on a camel to advertise a song called Sahara.

Different tricks were also performed, such as handing out bananas to crowds during performances of Frank Silver and Irving Cohn’s “Yes! We Have No Bananas.” When this became popular, Wright acquired a song titled “I’ve Never Seen a Straight Banana” and promised to give £1,000 to anyone who could find one. The office was soon flooded with boxes of bananas, and Wright ultimately awarded the prize to the individual who presented the least curved banana.

In 1933, Wright purchased the Princes Theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue and used it to showcase Blackpool revues to London audiences. Under the name Horatio Nicholls, he composed numerous songs, and as Lawrence Wright, he published thousands more, including popular hits like On the Sunny Side of the Street, Ain’t Misbehavin’, Burlington Bertie from Bow, and Old Father Thames. Wright was making a substantial amount of money and when his home in Maida Vale was destroyed by bombing in 1940, he moved into the Park Lane hotel where he resided until his death in 1964. He left behind a lasting impact as a prolific songwriter and played a significant role in the development of the music industry.

Source: theguardian.com