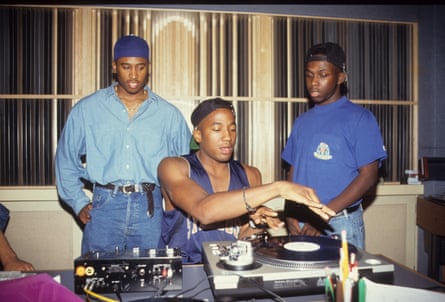

Hip-hop officially turned 50 last year. It is generally accepted that it was born on 11 August 1973, when 18-year-old DJ Kool Herc first cut up breakbeats at a party in the Bronx and his friend Coke La Rock rapped along, but this DJ-driven art form, which evolved parallel to disco, took another six years to spawn its first hit single, the Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight. The star MCs emerged in its second decade, each one redrawing the bounds of the possible. Run-DMC stripped it down, then Public Enemy blew it up. De La Soul made it friendly, Kool Keith made it freaky, NWA made it outrageous, and so on. Always changing, always expanding.

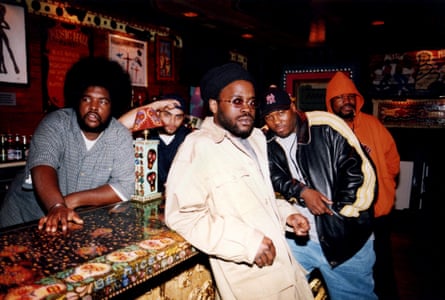

Nobody knows more about hip-hop, and perhaps popular music in general, than Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. Still drumming with the Roots, the Philadelphia hip-hop crew that have been Jimmy Fallon’s TV house band since 2009, he is also the Oscar-winning director of Summer of Soul, a prolific author, podcaster and DJ, and the man tasked with herding cats for the Grammys’ salute to hip-hop at 50. Two years older than the art form itself, he has become its unofficial curator, the Ken Burns of black music, the nerd’s nerd. “History is how change gets marked and assessed,” he writes in his eighth book. “It’s a communal form of memory and a collective acknowledgment that what we remember matters.”

In Questlove’s analysis, hip-hop is an eternal cycle of death and rebirth. It has always fetishised the new style: note how many MCs still use the prefix “Yung” or “Lil”. During its first two decades, it was dizzyingly ruthless. A debut record could change the whole game only for its creator to be eclipsed in turn a couple of years later. Longevity seemed impossible. But around the time XXL magazine convened 177 artists in Harlem for a 25th anniversary group portrait in 1998, hip-hop learned to appreciate its own heritage. When 20-year-old Queens rapper Nas released his stone-cold masterpiece Illmatic in 1994, it would have been strange to imagine that he would one day be performing a 30th anniversary tour, yet here he is, one of many revered elder statesmen.

Questlove has no allergy to hyperbole. When he compares the 1995 Source awards, the epicentre of the war between east and west coast rappers that contributed to the murders of Tupac and the Notorious BIG, to the Battle of Gettysburg, or the kick drum on the Pharcyde’s Bullshit to the French Revolution, he is only half joking. This is indeed a dramatic tale. During the 1980s, hip-hop went from delightful novelty to scowling bogeyman, with leading scold Tipper Gore claiming: “The music says it’s OK to beat people up.” Then, in the decade between KRS-One insisting “It’s not about a salary, it’s all about reality”, and the Notorious BIG boasting “It’s all about the Benjamins”, it became a money-making machine. New sounds from new regions produced new disruptions. Questlove was in the thick of it, fretting with each sea change that he was out of touch and washed up – “obsessed with the threat of erasure”.

For all the author’s wisdom and charm, his blizzard of names and facts is likely to overwhelm, rather than exhilarate, the uninitiated. The book at times resembles an annotated playlist, with the origin of one sample requiring no fewer than three sets of nested parentheses. Questlove is an idiosyncratic guide who admits that he values production over lyrics and candidly recalls his initial scepticism towards artists as significant as the Wu-Tang Clan or Lil Wayne – the time it took to absorb the shock of the new. This isn’t the history, then; it’s his history, as a fan, practitioner and chronicler of hip-hop.

Provided you have a little prior knowledge, it’s a wonderful ride, coloured by personal digressions and crisp observations. Questlove astutely identifies Kanye West’s fatal flaw as “the general lack of self-awareness, made worse by the belief that there is total self-awareness at work” and nails the older Eminem as a wheel-spinning virtuoso, “maybe with nothing to say any more, but with quite a talent for saying it” – a line that could apply to many veterans.

after newsletter promotion

Questlove’s life-cycle thesis is embodied by the 30-year journey of his favourite act, A Tribe Called Quest: the youthful chutzpah, the rapid maturation, the diminishing returns, the dispiriting break-up and the extraordinary comeback that became a swansong with the death of founding member Phife Dawg. I attended the launch party for that album, We Got It from Here… Thank You 4 Your Service, in Queens the day after Donald Trump won the 2016 election. Questlove was there, too, DJing classic hip-hop. Shellshocked and jet lagged, I almost cried. In that context, his turntable history lesson felt proudly defiant and utterly necessary, underlining the music’s essential claim: we are still here, despite everything. “So much of hip-hop is a reflection of pain,” he writes, “even the joyful parts.”

Source: theguardian.com