In the early hours of 2 January 1965, Anita “Margarita” Mahfood returned to the room she lived in on Rusden Road in Kingston, Jamaica, with her boyfriend, the trombonist Don Drummond. Margarita was the “rhumba queen” of the island, famous for her sensual and provocative dancing; Drummond was a trombonist, and a huge musical star. A founding member of the Skatalites the year before – the reggae band who celebrate their 60th anniversary at Glastonbury this weekend – Drummond’s jazz-inflected melancholy can be heard on hundreds of tracks that were coming out of the studios such as Studio One proliferating in Jamaica at the time, backing the Wailers, Jimmy Cliff and Toots and the Maytals among others. The way he melded jazz into the rhythms of ska paved the way for reggae to take over the world.

And yet this celebrated, non-conformist couple lived in little more than a shack. That night Margarita had been performing at Club Havana, a lucrative show thanks to its well-heeled clientele. Drummond was supposed to have played with the Skatalites the night before, but he’d overslept and missed the gig. Not long after Margarita got home, a neighbour reported hearing the couple argue. At some point before dawn, Drummond stabbed Margarita four times, killing her. She was 25.

Drummond handed himself in to the police and claimed that Margarita had stabbed herself. At first, it wasn’t clear he was fit to stand trial. It took more than a year for the murder case to go to court, where the jury unanimously found him “guilty but insane”. He was committed to Bellevue Mental Hospital, where he died on 6 May 1969 at the age of 35, the cause of death “congestive cardiac failure and anaemia”, most likely precipitated by the drugs he was on for schizophrenia.

Drummond would have been 90 this year. While researching her 2013 biography, Don Drummond: The Genius and Tragedy of the World’s Greatest Trombonist, the ska historian Heather Augustyn found that “a veil of secrecy still hangs over Don and Margarita’s story”. Speaking on the phone from her home in Michigan, she says that in Jamaica “a lot of young people don’t even know his name, even though his music is so tied to Jamaican identity. I was often told: ‘This is a story that’s left best alone.’ It’s a very dark story, a story of violence; it doesn’t make Jamaican music look good. But it’s his trombone playing that gives the Skatalites their heart – a large part of their repertoire comes from him. Everybody knows who Bob Marley is. But I’m going to stick my neck out and say Don was a greater musician than Bob.”

“There is a mystery to Don Drummond’s compositions … a very special atmosphere of tension and release,” says the jazz and classical trombonist Samuel Blaser from his home in Switzerland. In 2023, Blaser released a tribute album to Drummond, Routes, working with among others Lee “Scratch” Perry (whose work on the album was sadly cut short by his death). “No one plays like Drummond,” Blaser says. “He was a pioneer.”

As well as the murder, Augustyn’s book documents a life of poverty, racial injustice, exploitation and brutal medical treatment on the island. “Don was too good to stay in Jamaica,” says Vin Gordon from his home in Paris. The current trombonist in the Skatalites, Gordon was briefly known as Don Drummond Jr due to their similar playing styles – although without Drummond, their main star and composer, they broke up not long after his arrest and none of the original lineup survive. Perhaps if Drummond had managed to leave the island, get royalties for the estimated 500 tracks he composed and receive proper medical help, it would be a different story. “Playing with the Skatalites [and Don Drummond’s music], you get a chance to blow,” Gordon says. “Don’s sound is more like in the 50s; my sound is more modern, bebop. But people get to appreciate the damn instrument.”

The trumpeter Edward “Tan Tan” Thornton, who played with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, tried to get his old schoolfriend Drummond to join him in the UK, but the furthest Drummond ever travelled was Haiti with the Eric Deans Orchestra. His mental health was too delicate – and perhaps he was too immersed in the sounds of the island. As Gordon says: “Don Drummond’s music is purely Jamaican.”

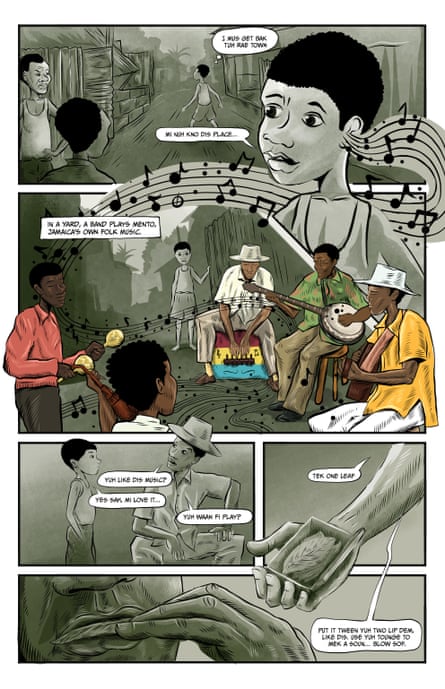

Drummond was born in 1934 in Kingston. His mother Doris was a cleaner, his father Uriah never part of his life. Mother and son were close but life was hard and, aged nine, having been found wandering the streets alone playing truant, Drummond was sent to Alpha Boys’ School, whose objective was to find trades for boys who came from poor backgrounds. Carpentry, gardening, tailoring and printing were taught alongside music. Discipline was strict: boys would be beaten for playing the wrong note.

Its alumni feature a Who’s Who of ska and reggae: both Gordon and Thornton studied there, along with founding Skatalite members Tommy McCook, Lester Sterling and Johnny “Dizzy” Moore; Cedric “IM” Brooks; Emmanuel “Rico” Rodriguez, whose trombone solo on the Specials’ Ghost Town Jerry Dammers described as the band’s “musical highpoint”; “Yellowman” Foster, and many others. Drummond’s musical talent was exceptional and he chose the notoriously difficult trombone as his instrument; he spoke little except about music and would practise obsessively.

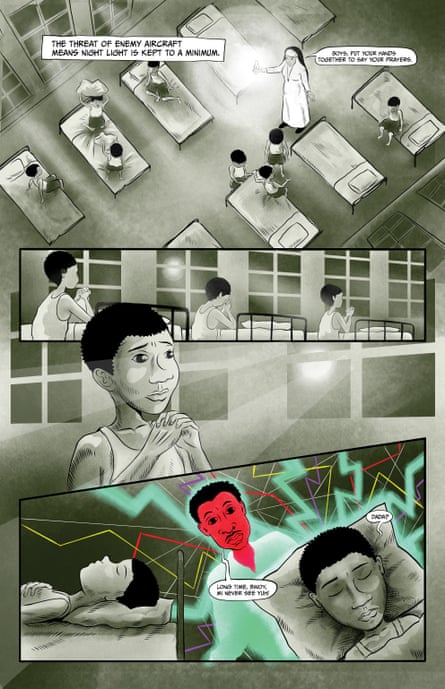

Sister Mary Ignatius Davies, a Roman Catholic nun, joined the school at the age of 17 in 1939 and stayed there all her life. Tall and thin – “Bones”, as the boys nicknamed her – Davies loved sport, including boxing; she would spar with the pupils in full habit, show them videos of fights and was pen pals with Sugar Ray Robinson. Music was her other passion: she played saxophone and put on records for the boys through a sound system she had built, seeing music as a viable way for her underprivileged wards to make a livelihood. Drummond and his fellow students were exposed to classical, Latin, jazz, Cuban and blues, Ignatius encouraging them to blend the styles they heard into their own music – a recipe for ska.

The school’s reputation brought scouts for bandleaders, and when guitarist Ernest Ranglin came knocking in 1950, she got him to hear Drummond and Ranglin signed the 16-year-old up for the Eric Deans Orchestra, playing jazz standards for wealthy tourists and the upper echelons of society. Drummond’s reputation grew, and by 1954 he had left and formed his own band, the Don Drummond All-Stars, and would get to play with visiting jazz greats Sarah Vaughan and Dave Brubeck. By the late 50s, he was a huge star in Jamaica and reportedly arranged the Wailers’ first hit Simmer Down, but rarely got paid the money he was due.

As Drummond got older, his erratic behaviour became more extreme: he would eat soil and bananas dipped in sand (symptoms of pica, which is associated with schizophrenia), urinate on stage during shows and stand in the middle of busy streets of traffic with his arms outstretched. He hated being photographed and regularly missed gigs and recording sessions, voluntarily admitting himself to Bellevue for months at a time. His treatment in the hospital would have been brutal, with the use of electroconvulsive therapy and powerful sedatives standard. Black men, especially poor ones, were often kept in cages, no better than tortured. We will never know Drummond’s proper diagnosis: his medical records are practically nonexistent.

In 2017, Augustyn and Adam Reeves co-authored Alpha Boys’ School: Cradle of Jamaican Music, in which they interviewed the surviving musicians and told the stories of those no longer alive, and this year Reeves has published the first of a seven-part graphic novel based on Augustyn’s biography. Trombone Man: Ska’s Fallen Genius is illustrated by Cypriot artist Constantinos Pissourios, who specialises in tributes to Jamaican music producers and sound system operators. Reeves uses Jamaican patois in the dialogue, translated by Mars Dilbert and Kingsley Jahsiah, and Count Ossie’s daughter Mojiba Ashanti read it for cultural sensitivity.

“I’ve been fascinated by Don Drummond since I was a teenager,” Reeves says. “There was always mystery around him … rumours. It was all kind of terrible. When Heather’s book came out, it blew everything wide open. But what I also really wanted to do was tell the story of the two women who shaped Don’s life: Sister Ignatius and Margarita. This story is as much about them.” Augustyn concurs: “Margarita deserves a part in this story, too. I didn’t want to see her identity as that of a murder victim.”

Anita Mahfood was born in 1939 into a privileged but troubled family. Her mother was white Jamaican, her father a successful businessman of Lebanese origin. Violent and abusive, obsessed with guns, he forced his wife to drink and she became an alcoholic, eventually killing herself. Anita was determined to become a dancer: self-taught, she entered talent contests as a teenager and was soon starring in the clubs, calling herself Margarita so her father wouldn’t know it was her.

In 1960, she married the boxer Rudolph Bent. He proved as violent as her father, beating her and their children. She divorced him in 1964, by which time she was in a relationship with Drummond. They had known each other from the club circuit in the 50s but they fell in love in Wareika Hills outside Kingston where bandleader Count Ossie held his Rastafarian camps: musicians would go up there after the clubs had closed to jam all night and smoke ganja, as Ossie introduced them to a Rastafarian style of drumming. Drummond revelled in the freedom it offered to improvise, and he was soon bringing other members of the Skatalites.

Margarita was also a frequent visitor and began to incorporate Rastafarian drumming into her rhumba, bringing its rhythms into the mainstream at a time when Rastafarians were deeply persecuted – the police were authorised to seize any men on sight and shave their heads, and destroy their camps. “She was incredibly brave,” says Augustyn. “She would tell the club owners that she wouldn’t dance unless they let the Rasta drummers play as her backing. These people were considered the lowest of the low. The owners would relent because she was the star.”

Margarita fell in love with Drummond and his music. In 1964, she recorded the song Woman a Come: one of the few tracks of the time written and sung by a solo female artist, and a love letter to Drummond. “It sounds like she is singing one melody, while the band is playing another,” says Augustyn. “This gives it a very unusual sound – quite haunting in hindsight.” But the relationship was fraught and Drummond’s mental health worsening, perhaps exacerbated by the amount of ganja he was smoking up in Wareika. She refused his jealous demands to stop dancing and tried to shrug off his increasingly violent behaviour.

Both Drummond and Margarita are now often thought of in the context of the murder, if thought of at all – but Reeves and Augustyn are determined to change that. As well as the graphic novel, Reeves says there are plans for a stage show and TV series based on Drummond and Margarita’s life – deservedly so, given the extent of their influence. “Ska was the first music where people danced freestyle on their own, not in a couple, to infectious music. It happened first in Jamaica, this tiny island that punches musically above its weight, and laid down the roots of rave and club culture.”

Source: theguardian.com