There were people who thought Drake v Kendrick was the greatest hip-hop beef of all time, attracting a wider level of public interest and proceeding at a more dizzying velocity than any previous feud: the parties involved released 10 tracks in the space of six weeks, more if you count J Cole’s withdrawn 7 Minute Drill and producer Metro Boomin’s BBL Drizzy, released as a contest to see which member of the public could add the best insult of Drake to the instrumental beat.

On the other hand, there were high-profile naysayers, among them rapper Macklemore, who complained that the feud was distracting attention from the war in Palestine; and Roots drummer, DJ and hip-hop historian Ahmir ‘Questlove’ Thompson, who called it “wrestling match level mudslinging and takedown by any means necessary” for an “audience wanting blood [that] will soon put up RIP posts like they weren’t part of the problem”: proof, he suggested, that “hip-hop is truly dead”.

But there was little debate about who won the battle: it wasn’t just that Lamar’s Not Like Us landed a series of blows on Drake that genuinely seem to have damaged his reputation, it was the sheer scale of its success. No other diss track in history has ever gone to No 1 on the Billboard Hot 100; unequivocally the biggest hip-hop single of 2024, Not Like Us has been nominated for five Grammys. Drake released a response called The Heart Part 6 the day after Not Like Us appeared, and the reaction was so negative that Drake quietly deleted an Instagram post promoting it.

And that, one might reasonably have assumed, was that, until November of last year, when Drake unexpectedly filed a petition against Universal Music Group – which releases both Lamar’s music and his own – and Spotify accusing them of deceptive business practices: they had, he claimed, used bots to stream the song and “deceive consumers into believing [Not Like Us] was more popular than it was in reality”. The following day, he filed another petition against UMG under Texas law claiming defamation – Not Like Us had “falsely” accused him of being a sex offender – and a payola scheme involving internet radio platform iHeartRadio. UMG and Spotify denied the allegations.

Earlier this week, he withdrew the legal petition – but then filed an actual lawsuit against UMG: Not Like Us, it alleges, was “intended to convey the specific, unmistakable, and false factual allegation that Drake is a criminal pedophile, and to suggest that the public should resort to vigilante justice in response” and his own label “decided to publish, promote, exploit, and monetise allegations that it understood were not only false, but dangerous”. UMG have repeated their denial, calling Drake’s claims “untrue” and “illogical”.

The view that these are the petulant actions of a very sore loser has been regularly expressed. That said, you can understand why Drake might feel driven to the defamation suit. The lyrics of Not Like Us alter the title of his 2021 album Certified Lover Boy to “certified paedophiles”: “I hear you like ‘em young … just make sure you hide your little sister from him,” taunts Lamar, presumably in reference to a 2010 video that showed Drake kissing a fan on stage at a show in Denver, shouting “I can’t go to jail yet, man!” when she revealed she was 17 (the legal age of consent in Colorado), then adding: “I don’t know if I should feel guilty or not, but I had fun. I like the way your breasts feel against my chest.”

The video made headlines when it resurfaced in 2019, but accusations of sexual impropriety feel even more pointed in the wake of ongoing allegations against Sean Combs – currently awaiting trial in New York on charges of racketeering, sex trafficking by force, and transportation for purposes of prostitution – and Jay-Z, who in December was accused in a civil lawsuit of raping a 13-year-old girl with Combs at an MTV Video Music Awards afterparty in 2000 (Jay-Z denied this, and filed both a motion requesting that the accuser identify themselves and a lawsuit against the accuser’s attorney).

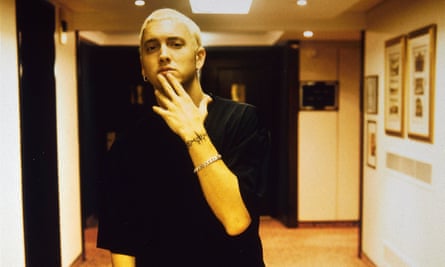

How Drake’s case will play out is an intriguing question. There aren’t many precedents for a defamation suit based on song lyrics. In 1999, Eminem’s mother, Debbie Mathers, attempted to sue her son for $11m (£6.8m at the time) over lines about her drug use on his album The Slim Shady LP: she was eventually awarded $25,000 (£15,500), and after paying her lawyer was left with just $1,600 (£1,000). In 2005, a case brought by record producer Armen Boladian over lyrics on rapper Warren G’s 2001 track Speed Dreamin’ – which called him “a disgrace to the species” and a “big nose motherfucker”, and suggested he should have “faeces” thrown at him – was dismissed, with the offending lines judged to be “rhetorical hyperbole”. Both Drake and UMG might note the wording of the judgment: “There was no specific allegation, such as an act of child abuse, that could be proven.”

But “rhetorical hyperbole” is an interesting phrase in the context of Not Like Us. The alleged defamation took place in the midst of a beef involving umpteen diss tracks. Anyone conversant with hip-hop history knows that the world of the diss track is a peculiar kind of space in which outlandish claims and insults are taken as standard fare: they’re spiteful, nasty, obviously intended to be wounding and often clearly untrue. They have their critics, who often worry about the consequences if the abuse spills over into real life, which it clearly has done more than once in the past, occasionally with deadly consequences: “Those were dark times if you were there,” wrote Questlove, a man who found himself literally in the middle of the warring east coast/west coast factions at the 1995 Source Awards, one of the flashpoints of the feud between 2Pac and the Notorious BIG that left both rappers dead.

But diss tracks are also an integral part of the genre, almost as old as hip-hop itself. You could, if you were so minded, draw a line connecting Not Like Us to the insults traded by UTFO and Roxanne Shante in 1984’s Roxanne wars, or the row between MC Shan and Boogie Down Productions over hip-hop’s true birthplace in 1986, although it’s hard to do that without also noting that diss tracks have become more pointed in a faintly troubling way in recent years, dragging artists’ families and, increasingly, children into the firing line as a means of scoring points. No one is ever going to hold up Ether, Nas’s 2001 evisceration of Jay-Z, as a model of decorum, but it still feels like it’s made of different stuff to Pusha T’s stakes-raising The Story of Adidon, an all-out 2018 assault on Drake’s personal life and mental health that one critic described as “bringing a gun to a knife fight”.

If Drake’s suit is successful, it throws a hand grenade into a whole area of rap culture. Even if you think the said area could do with cooling down a few degrees, the notion of using the courts to do it is a deeply peculiar one at best; the idea that rappers making diss tracks will be forced to mind their manners or face legal consequences feels somehow antithetical to the whole business, and you could easily depict it as a form of censorship. The case comes in the wake of another rap superstar, Young Thug, being put on trial with his lyrics used as supposed evidence against him, which was criticised as an assault on free speech and artistic expression. Many will see Drake’s lawsuit as doing the same – and against a fellow rapper, no less.

It doesn’t take a huge leap of imagination to see Drake being painted as a man who singlehandedly destroyed a longstanding rap tradition that he was perfectly happy to engage in for years – feuding on tracks with everyone from Kanye West to Meek Mill to Tyga – because he was bested at it. A victory in court could turn out to be pyrrhic.

Source: theguardian.com