How odd to meet the UK’s most exhilarating live act around a wipe-clean table in an anonymous boardroom, as though we’re about to discuss some new accountancy software. The door shuts with an air-tight sigh. We shuffle into our chairs.

The Ezra Collective vibe is usually effervescent, upbeat, in the moment. You could see it when they won the Mercury prize in 2023, the first jazz act to ever do so, utterly shocked and overjoyed to win. Then, they were a happiness pile-up, a bundle of hugs that actually ended up on the floor. Today, to my right is band leader and drummer Femi Koleoso, a serious man whose grin is like sudden sunshine. Then, going around the table, we have keyboard-player Joe Armon-Jones (strawberry-blond mop), trumpeter Ife Ogunjobi (quiet, locs framing his face), bassist TJ Koleoso (Femi’s younger, more relaxed brother) and saxophonist James Mollison, who says little beneath his long curls, but smiles a lot. Talking in an office environment is not what they’re about, though it turns out they’re good at it.

What Ezra Collective are about is multi-fold and generous, but everything starts at the same place: they’re a live jazz band. Their songs, which bury into your soul, aren’t strictly jazz – they embrace elements of Fela Kuti, Burna Boy, Afrobeat, funk, reggae, Latin, hip-hop, soul – but, as a group, they’re rooted in the fundamental jazz ethos of creating music in the here and now. Reacting to one another, bringing in a crowd, ensuring that everyone in the room with them is having a fantastic time, too. “We destroy any impostor syndrome with our first tune,” says Femi. “We get everyone to feel a part of what’s going on.”

They are such a brilliant band to watch, whether outdoors at a festival, or in a tiny sweaty room. Though you’ll be hard-pressed to find them in a little space these days: they’re playing Wembley Arena in November (Femi: “We’ll get that arena to feel like a pub, like it’s just 20 of us here”). If you haven’t had the pleasure, then take a look at their performance of Victory Dance after they won the Mercury prize. Or perhaps you spotted them on this year’s Strictly, playing their single God Gave Me Feet for Dancing. With Yazmin Lacey on vocals, two of the show’s professional dancers did their overdramatic twirly thing as Ezra Collective locked in. To me, it was weird to have the focus taken off such a great band, but that’s because I’m wedded to an olde pop approach. Ezra Collective are less ego-driven, more democratic than that. “Yes, I watch Beyoncé and I want her to come in on a white horse with diamonds,” says Femi. “But this is a different thing.”

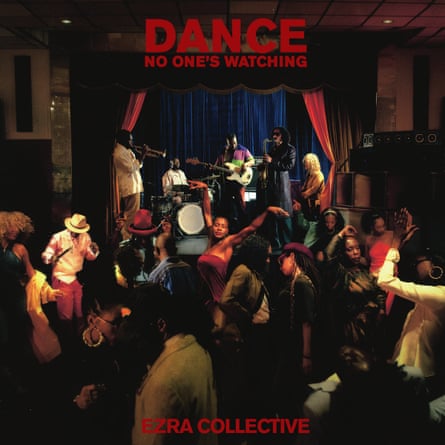

You can intuit the band’s approach from the cover of their latest album, Dance, No One’s Watching. The LP – which just debuted in the charts at No 7 – is structured a little like a night out (there are string-based intermissions called Cloakroom Link Up and Lights On, and a song, N29, named after the night bus to Enfield), but the artwork puts the group at the back of the picture, on a small stage, like a house band in a 60s niterie. It’s the people on the dancefloor who are highlighted and foregrounded, dancing in their own little worlds, stars of the show.

“In the picture,” says TJ, “no one’s looking at each other, no one’s watching, because that’s what we’re trying to do with the music. We make it so everyone’s secure. Level the platform so that everyone feels like they’re part of this. Because it’s in those moments that freedom happens.”

“The dancefloor encapsulates what life is,” says Femi. “You can live your life without the anxiety that’s stopping you from dancing. No One’s Watching is saying: ‘Don’t be petrified, because this facade you built up of everyone scrutinising you might not be as real as you think it is. Take the entire moment with both hands for yourself.’”

It’s not always easy to move through life, or even around a dancefloor, as though you’re not being judged. The band understand this, because they remember when they weren’t so confident. TJ recalls being at university (Brunel, he studied physiotherapy): “I was just so concerned about how I was going to be perceived by this person or that person, or maybe this girl’s looking at me, all of that kind of stuff.” Femi remembers when the band used to try to fit into social mores. “We would be like, ‘Oh my gosh, kicking [playing] a jazz club, get your suit out.’ I remember genuinely thinking, ‘We’re playing before a pop act. Shall we play some pop tunes to try and make it fit and make it work?’ We used to be intimidated by a room.”

It was playing Glastonbury in 2019 that changed this, they think. They were on the West Holts stage at 2pm. Not the jolliest of slots and not their natural audience; but they killed it. “We just went out there, no shame, not scared, no hiding, just blasted through,” says Femi, and the crowd responded. Now, having played all around the world, they’re experienced enough to know how to get everyone going, even if there’s a language or cultural difference.

They create their songs through performance: “We’re a live band that’s learning to put this stuff on record,” says TJ. This is partly because that’s how it’s done in jazz, but also because, for years, they didn’t have enough money to pay for a studio. Their first recording was in a school – Oasis Academy in Enfield – where Femi was teaching drums, so he could sneak them in. Now, when they go into a studio, they make sure they don’t waste a moment, not even for lunch. “No waiting for 45 minutes for Deliveroo,” says TJ. “You order it before, so it gets there on time.”

“We know how much money it costs,” says Joe. “We can remember when it was £300 a studio, so if you’re two hours late, that’s a waste of money.”

They do their own production, and the last time they did some recording, says Femi, “we came out with five clean compositions. Done. Recorded. In one nine-to-five session. And that was us slowing down. Usually it’s five songs in like, an hour and a half.” Now they’re getting bigger, they get some better studio situations: straight after the Mercury prize, they went into Abbey Road to record Dance, No One’s Watching, having developed the songs during their travels the year before. It was carnival weekend and the band’s friends and family came down, including Femi and TJ’s old music teacher, as well as Ian Wright. Wrighty called up a friend in the middle of the recording and you can hear him at the start of Shaking Body saying “still here bro, dancing, lovin’ it, it’s amazing”. And you can hear the chaos and chatter of the room in some of the tracks such as Ajala, but the clarity and beauty of the music cuts through as well. Like a full on night out clubbing.

But, though they love a dancefloor (James, apparently, is the one who gets on there first and leaves last), Ezra Collective are also about a different type of club. They define themselves as coming out of London’s youth clubs. The genesis of the band was formed more than a decade ago, at Tomorrow’s Warriors jazz youth club in Camden, where Femi, TJ, James and Joe all met. (Ife, younger than the others, met Femi through carnival collective Kinetika Bloco and joined the band after their first album.) Joe grew up in Oxfordshire, and went to Eton; Femi and TJ are from Enfield; James from Catford. They wouldn’t have met if it wasn’t for Tomorrow’s Warriors. Music and free youth clubs brought them together, and all of them are passionate about what youth groups can do.

“The way that we came into music as a band has shaped our way of doing things,” says TJ. “We don’t have much that we weren’t given. We were given a lot by way of advice, approach, teaching, tuition, all of that kind of stuff. And, to us, that’s an advantage… It’s not the same for everyone in music. I guess with a lot of people [in pop music], they’re told the whole time to have a big ego, like, ‘You’ve got to go in that room and be the best.’ We’re not that.”

Joe: “With pop, it has to focus on an individual, but this is a group and as a jazz musician you have to learn how to lead, but then you’re also supporting.”

Femi: “A skill that I’m really good at that’s not that useful – I’m very good at jumping on a drum kit when someone else is playing and taking over and not losing the rhythm. For us, that’s what instruments are for. It’s just like, ‘share, move up’.”

At the youth clubs, they found older people who would say, let’s learn this song together, and that’s what they try to pass on to the younger generation now. I speak to Maia Avery, 18, saxophonist with jazz group Youthsayers and Kinetika Bloco. Ezra Collective are her favourite band, so she was utterly overwhelmed to be invited as one of around 30 young musicians to play with them at Glastonbury in 2023. Femi had been teaching at Kinetika Bloko and asked them to play. “It was crazy,” says Maia, “Like an out-of-body experience.” They played on a couple of songs, but also at the end, came on stage just to dance. “And Femi does this thing where he gets everyone in the audience to go down low and then jump up,” says Maia. “And everyone, all 35,000 people, all did it!”

What she loves is that Femi, especially, tells them, as young musicians, that they can do it, too. “We went to the Mercury afterparty and he said: ‘Thanks for coming, this is for you guys, this will happen to you soon.’” Moving in nerdy jazz circles, she worries that she’s not up to scratch technically, but Ezra Collective make her feel like she can be on stage, too. “With pop, you get the idea you don’t have to be the world’s greatest, but that’s not the same with jazz. But they make you feel like you can achieve this, it’s not out of reach.”

The band are busy: Joe and TJ have solo careers, Femi spent a lot of 2022 as the drummer in Gorillaz. (He finds Damon Albarn’s approach to music very inspiring. “Like a diary, recording on the road… I love that he’s not that precious with music, and that is something I’m really trying to get into.”) But they all go into schools and youth clubs, teaching and encouraging kids. More: Femi set up a summer camp for teenagers a decade ago, and now takes 400 of them camping for five days in July. The band live the “each one teach one” idea to the full. “There’s so many teachers that I had when I was younger that went the extra mile,” says Ife. “They gave me extra because they knew I was interested in music.”

They don’t care whether or not anyone is “good” either: it’s more than that. It’s about practising something until you become better at it.

“If you enjoy something as a kid and then you keep doing it for a long time, that turns into what people would describe as talent,” says Joe. “It’s very rare to see a god-given talent, a prodigy.”

“You have to try to coach people to fall in love with the frustration of music, going over and over until you get it,” says TJ. “Frustration is good. Imagine you don’t even become a musician, but you learn to lean into frustration and lean into the thing that you’re not good at. How good do you get at everything else?”

How about politics? I wonder. Are they excited by the new Labour government? There’s a pause.

“The culture that is maybe the most damaging right now is this culture of sitting back and expecting the government to do absolutely everything,” says Femi. “The culture I’d implement is: ‘What do you have in your hands? How can you use it to bless someone else?’ If everyone had that, the world would be a much nicer place. And I think that’s the question you should ask. ‘What did you do with what you had?’ And some people have a paintbrush, some people have a keyboard, some people have words, some people have time, you know? Government funding is great, but if the kid that lives next to you on your road hasn’t got a saxophone and you’ve got three, forget about the government funding. You do it.”

“You’re from the Observer,” he says. “I would ask them, how many schools could they go into and do writing camps? And maybe the Observer could have a teenage version, which is all done by kids. If every single child that you were to teach how to really interview people, and then the next time you get a really sick interview with Stormzy, instead of you doing it, you gave it to the kid, I promise you that kid will never stab someone in their life, because you’ve opened their whole mind to another way of life. And that’s the mission.”

-

Dance, No One’s Watching is out now on Partisan Records. Ezra Collective play the UK and Ireland, 5-15 November

Source: theguardian.com