The punks said that anyone can be a musician – but for proof that this may not be true, play Kim Kardashian’s 2011 single Jam (Turn It Up), a pop-EDM track that is somehow lethargic, alienating and overstimulating at the same time.

You can’t blame Kardashian for trying her hand at pop, of course. Music history is littered with models, socialites and tabloid figures who thought that making a record was their ticket to lasting celebrity – or, indeed, who genuinely thought that they possessed musical talent worth sharing with the world. For every Karen Elson – who parlayed modelling into a successful career as an alt-country darling – there is a Tyra Banks, whose reported six-year attempt to break into pop produced only one song, the woeful Shake Ya Body.

Nonetheless, model turned singer is the career pivot that refuses to die. This month sees the release of Paris Hilton’s second album, Infinite Icon – her follow-up to 2006’s reviled-and-eventually-reassessed Paris, which gave us the now cult single Stars Are Blind – as well as a new album from Suki Waterhouse, whose music career has been so outrageously successful, with 500m streams and counting on Spotify alone, that it’s likely much of her gen Z fanbase doesn’t even know about her past life as a face of Burberry.

“If you have this kind of fame, why wouldn’t you parlay it into something that could make more money?” says Rich Juzwiak, a critic who has written extensively about Hilton’s extended business ventures. “For a lot of people, it’s probably not that different from investing in real estate. You get a little bit more of a public ego kickback, but I think it’s just a way of diversifying your portfolio, predicated on the belief that this will be easy.”

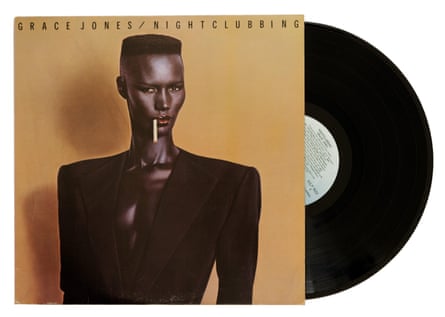

Juzwiak says Samantha Fox is the only model turned musician who “has launched a viable pop career”, scoring a No 3 single with Touch Me (I Want Your Body) in 1986. “She was always so dismissed, but she’s the actual template, and I think the reason why is because she leaned so much into the Page 3 thing,” he says of her frequent topless appearances in the Sun. “She was a woman who was highly sexual in public and she said: ‘OK, what if I did that sonically?’ And it totally worked.” Grace Jones was even more successful in finding the music to match her dramatic, even fearsome, appearance; her recording career has stretched from the late 70s to the present day.

Tailoring the music to the narrative of your career, as Juzwiak says, tends to work better than simply picking an A-list producer and praying for chart impact. When the US model, actor, tabloid figure, artist, podcaster, designer and author Julia Fox released her debut single, Down the Drain, this year, it felt more like a curio, born out of a sincere desire to create something outre, than a bid for pop stardom. True to the song’s grimy, art-kid aesthetic, Fox debuted the track at Charli xcx’s hyped Boiler Room show in Brooklyn and reportedly blew out the speakers – a Bianca Jagger-at-Studio-54 moment for the terminally online Zoomer crowd.

For the most part, though, models turned musicians are usually aiming for the top of the charts. But it doesn’t always go too well. In 1994, afour years after she appeared on Vogue’s iconic Supermodels cover, Naomi Campbell released Baby Woman, her first – and so far last – album. Hot producers including Gavin Friday, Tim Simenon and Youth, AKA Martin Glover, not to mention a video in which Campbell looks typically gorgeous in the company of elephants, were not enough to save it from commercial oblivion – it failed to chart in the UK.

Glover says that success is never a guarantee when you are making a pop record, even if you are one of the most famous people in the world: “It’s like when Mick Jagger does a solo album and nobody buys it.” When working with Campbell on Baby Woman – on a cover of Sunshine on a Rainy Day, which he wrote in 1990 with his then wife, Zoe – Glover operated out of a five-room studio in Brixton and employed about 15 staff. “I’d never seen the place so excited than when Naomi came in – the whole place was jumping. Someone who has that kind of reach, there’s a sort of enchanted air around them,” he says. But the star of the day, it turned out, wasn’t Campbell: “What even eclipsed Naomi’s charisma and buzz was her mother – she was almost even more beautiful than Naomi, and charming as well. It was great fun.”

Contrary to the assumption many may have of non-musicians who turn to music, Glover says Campbell “could basically hold a tune – this was in the days before AutoTune” – and was easy to work with, despite her formidable reputation. “She was very easy to direct – I mean, she’s not a Céline Dion, but then nor is Brigitte Bardot” – who had hits in her native France with Serge Gainsbourg. “The song wasn’t ambitious enough to make it difficult and she sang it with some emotion – that’s great.”

Not every musician who has been drafted in to work on a record with a model or a socialite says the same. When reached for comment for this article, one songwriter who worked on Hilton’s first album said they would “politely decline. As our mothers always taught us, if you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all.”

after newsletter promotion

The Lemonheads’ Evan Dando, on the other hand, says he “spent 20 years doing coke and hanging out with models, so I know a lot about the subject”. A longtime friend of Kate Moss, he and the producer Gibby Haynes enlisted the legendary model to sing the Dutch electronic duo Arling & Cameron’s Dirty Robot on the Lemonheads’ 2009 covers album. “Kate is smart, she’s like the girl next door: she’s beautiful, yes, but I think it’s her brain, really, that got her where she is,” Dando says.

Moss, he adds, would rather listen to music than make it, but has nonetheless been involved in projects with bands such as Oasis, Primal Scream and Babyshambles, the solo project of her ex-boyfriend Pete Doherty. “She would rather put her leg up and pretend it’s a guitar – she gets into fan mode,” Dando says. “If we’d be in Jamaica, she’d be the one sitting up all night, singing with me. She loved singing [the Velvet Underground’s] Sweet Jane over and over again, or making up new lyrics to My Favourite Things from The Sound of Music. She can do it visually really well – once, a Natalie Imbruglia song came on and she went away and got dressed up like her and made her hair look like her.”

Dando cites the flame-haired Lancastrian Elson as a prime example of a model who has a heartfelt artistic drive to make music. “All pretty girls like to take pictures of their feet – but that doesn’t mean they’re a photographer,” he says. “The people who don’t have the talent, they’re not going to stick with it, but the ones that really have the talent, they’ll do it.”

Commitment is what separates the wheat from the chaff when it comes to the transition into pop, says Juzwiak. He cites Hilton’s Stars Are Blind – a hit, but not an inescapable smash at the time it was released: “That song is good, but I don’t think Paris Hilton is the thing that makes that song good. She delivers it – she didn’t fuck it up. Whereas I could totally hear Gwen Stefani singing that song and owning it, because she has that pop thing that makes her very captivating.”

Clearly, there is far more to pop stardom than looking great on camera. “You’ve got it or you don’t,” Juzwiak concludes. “And you find out real soon after entering the stage whether you have it or not.”

Source: theguardian.com