In 1977, after Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti criticised the military regime in his native Nigeria, 1,000 government soldiers raided his compound, Kalakuta Republic. They beat and raped its inhabitants and threw Kuti’s 78-year-old mother from a second-storey window, ultimately killing her. Despite the attack, Kuti continued to use his music as a way to speak out.

Meanwhile, Roy Ayers – my father, with whom I have never had a relationship – was riding high on his 1976 hit song Everybody Loves the Sunshine. While he wasn’t especially political, he and Kuti had common ground in their pan-African beliefs. Ayers’s lawyer, who was Nigerian, convinced him that he and Kuti should link up. “You should go to Africa,” he said, “because there’s a musician I want you to meet.”

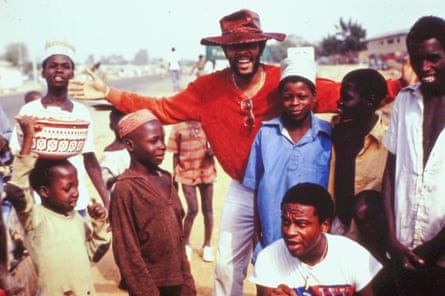

Ayers agreed and his lawyer arranged the logistics. Ayers duly travelled to Nigeria in 1979 to tour with Kuti. A resulting album, Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti and Roy Ayers: Music of Many Colours, was released in 1980 and drew widespread acclaim. But little is known about the tour that spawned it. Taking place when Nigeria was in a state of chaos, with government corruption prompting frequent unrest and subsequent violent crackdowns, it turned out to be a death-defying struggle.

Writing my memoir My Life in the Sunshine brought out dozens of new paternal connections including Chi’cas Reid, 73, a vocalist in Roy Ayers Ubiquity from 1975 to 1979 – the female voice you hear on Everybody Loves the Sunshine – and Henry Root, 71, Ayers’s road manager during the same period. In a video call along with 84-year-old drummer Bernard Purdie, I asked them to tell me everything about their time touring Nigeria.

Chi’cas Reid Roy’s lawyer set the tour up. I thought it was a chance – the beginning of a big career for me. Even though I’d played in different states and South America, going to Africa was a big thing. But once we got to Nigeria, we were thrown to the wolves. They took our passports.

Henry Root We were staying at the Holiday Inn – the best hotel in Lagos. The night we got there you could hear gunshots from our hotel. They were tying people to sand-filled oil drums and executing them on the beach nearby.

Bernard Purdie None of us knew what was going on – and we couldn’t leave the hotel because there were guards keeping us there.

Reid Some days we had electricity, some days we didn’t. It was like stepping back in time: people were living with mud floors, anthills were as tall as trees. Things that I’d never seen before or even seen in National Geographic.

Root On the second night, Fela had all of us out to his compound, Kalakuta. That was a crazy scene. Complete chaos.

Reid Fela was performing when we showed up. His dancers were hanging from the ceiling in cages. It was like Studio 54 but in a smaller setting.

Root He then took 28 of his 31 wives on tour with him. And they were all under 21, if not under 18.

Reid The wives were in their costumes all the time. And they dressed me up and gave me makeup. It was wild. People were smoking weed as big as cigars, man. Everyone was smoking all day all night, all the time, out in the open.

Root I was the only white guy on the tour. The night we met him, Fela told Roy to send me home because I’d get killed. And Roy gave me a choice to stay or go home. I was like, I just got here. Of course I’m staying. I had to get the equipment out of customs. A big newspaper sponsored the tour, and every day a guy from the newspaper would pick me up at the hotel and we’d go to the airport and meet with this beefy guy who wouldn’t give us the equipment. Finally on the third day, the newspaper man told me to give the man $500. I said, “Why didn’t you tell me that three days ago?!”

Reid Once it started, the tour unravelled. We felt like we were confined in a country where we didn’t have any say.

Root There was not really an itinerary. The newspaper would print where the tour was. So I’d tear a page out of the paper to find out where we were supposed to be. But I still had no idea where the cities were.

Reid A lot of the townships we visited were very strict and didn’t want us playing the music we played. They also didn’t like that Fela had all those wives.

Purdie One night on the bus, someone jumped up and told the bus driver to stop, stop! We stopped about six inches from a hole in the road from a bomb that blew the road away. It was in the middle of the night, so we couldn’t travel at night after that.

Reid We couldn’t travel in the day because people would see us, and Fela was wanted. So we had to travel very early in the morning. And the little buses they had for us, we all had to pack in, and just hold on to what we had. There were no roads. We would look down and see the trucks that had fallen off the cliff below us.

Root I only rode in the bus a couple of times when the villages we were going to were too dangerous. [On one occasion] people said there were robbers up the road who would kill anyone who stopped. But some people said this is a dangerous village, if you stop to sleep here, they’re going to come on the bus and rob you and kill you. So we have 25 adults having a serious conversation about whether we wanted to get killed on the road ahead or killed in this village. I remember saying I’d rather be moving than sitting here, so we continued driving and never saw any robbers. Those were the kinds of decisions we were making almost every day.

Purdie Every day. Every day.

Root At Kalakuta that first night, Roy and Fela had a conversation about who would headline. Fela said: “You’re my distinguished American guest, you headline.” And Roy said, “No, you drive the music market here, you headline.” They went back and forth and finally to be polite, Roy agreed to headline. Fela did a four-to-six hour show before Roy could go on and that was the last time we headlined.

Reid He played one beat all night long. All night. Like until four or five in the morning.

Purdie He’d play his horn, get tired, go sit down, and then the percussionists started playing, then he comes back a half hour later, goes at it again. I mean, it was amazing. When we finally got to another city, we realised that we could go eat or do something else instead of wait for Fela to finish his six-hour set.

Reid Once I got up on the stage I did my thing, I was good to go. They treated me like a queen. I had a good time once I was outside of the fear.

Root Every opportunity he had, Fela would go lecture at a school and I would listen to him talk about freedom and independence and how the country had been oppressed by the white people.

Reid I remember when some of the kids or the women would touch Henry’s skin or his hair. They just couldn’t believe there was a white man in their village.

Root At an outdoor amphitheatre in Kano or Kaduna, there was a riot and they turned over Fela’s bus and set it on fire the first night. And we were stupid enough to go back and play that venue a second night. Fela’s bass player comes in for sound check, and he’s got his bass guitar over one shoulder, and a bow and arrows over his other shoulder. I’m this white-bread guy, a sociology major in college, and I’m looking at these arrows. I asked what he was doing and he explained that last night people threw rocks from trees, and that if they did it again, he’d be ready.

Reid I toured Latin America with Joe Cocker, with Keith Richards in the band. That was laid back compared with this.

Root We played this huge soccer stadium that must have held 25,000 people. The stage was plywood nailed to planks set up on oil drums. The lights were fluorescent tube lamps nailed to the side of the stage. And the power was an extension cord running to the locker room across the field. The walls were three storeys high, and there was a riot outside the stadium, and the cops came and teargassed the audience. So Roy’s band is on the stage performing, and all the tear gas is coming over the wall and they’re all choking and crying.

Reid People were running everywhere, it was terrible.

Purdie I’m so glad that I didn’t know what was going on at the time. I probably would not have played if I’d known.

Root It was all crazy, single, drunk guys with no women. That was the audience.

Reid It was all men drinking beer inside the stadium, and all women selling food out on the street. And you guys protected me!

Root This big muscular guy Patrick was one of Fela’s lieutenants. He wore a black beret. One night around 4am, a bunch of military police pulled the equipment truck over. They pointed Uzis at me and the crew, and they made us take all the equipment off the truck and open all the cases. Then Patrick and his crew came screaming to a stop. Patrick jumps out of the car and runs up to the military police and he starts taking their Uzis out of their arms and throwing them on the ground and stomping on them and yelling at them for holding me up. I thought I was gonna get shot that night. We were supposed to come home for Thanksgiving.

Reid We told Roy we were leaving, but by then he’d connected with Fela to record this album together. We were all at the end of our rope. Everybody was ready to quit and fly home. Bernard and I finally decided we were getting out of there. They had taken our passports when we arrived, but I met a guy that worked at the airport. There were no sexual favours or anything, he was just so humble, and he got us our passports back. We played at a big concert hall, and we told Roy that we were leaving at 11pm. He didn’t believe us. I walked off the stage, Bernard walked off the stage, the band kept playing without us, and we went straight to the airport. When I got off the plane in New York, I kissed the ground. I weighed 40kg (90lb). I was so skinny, when my mom finally saw me she just cried because she couldn’t believe it. I never told her what we went through. Bernard had more clout than I did because he was already an established musician, so he played with Roy again. But Roy got another lady to come in and finish the recording I was working on. It was the song You Send Me. After I walked off that stage in Nigeria, I didn’t see Roy until 2017.

Root I stayed for the recording [of Music of Many Colours] at the Phonodisk studio in the middle of the jungle behind a walled compound. I knock on the door and I meet Chas Gerber, a guy from Philadelphia I’d toured with before who, it turns out, ran the studio. He told me not to leave the compound – that it was dangerous in the village because they’d burned a lady at the stake the night before for being a witch.

Reid I mean, the whole country was breathtaking. The people. The traffic. The beaches were beautiful. It was a lifetime experience and I’m grateful that I got to see the other side of the world. Now I can understand why everybody’s trying to come this way.

Root When I got back, it was probably two weeks before I could talk to my family or my girlfriend about what we’d been through. There just weren’t words to describe the feelings and emotions.

Reid It was so traumatic that I needed a break. Eventually I started doing little gigs around town. Then I hooked up with Gil Scott-Heron. But once I really, really wanted to get back into it, I wasn’t able to. I’m in a place now at peace. I have to remember that I made history, and I’m an icon. Because I put myself down for a long time after the traumatic experience I went through. But I’m grateful for people like Purdie and Henry who kept me grounded.

Root You guys were the adults in the room. Everybody else was smoking pot and crazy, and you guys were intelligent and grounded and made articulate decisions.

Purdie When you stop and think about it, we enjoyed ourselves because we were doing the music. We looked after each other throughout the whole trip, no matter what.

Reid We saved each other’s lives.

Source: theguardian.com