For a few seconds, before the on-field celebrations degenerated into a brawl between football’s newest worst enemies, France and Argentina, it was all about joy. The passionate chorus that had shaken the Stade de Bordeaux non-stop for two hours of white-knuckle football reached a deafening fortissimo.

One man stood apart in the collective delirium. He seemed consumed not by relief or exultation, but by fury. He repeatedly hit his temple with his index finger. Other managers would have sunk to their knees or embraced whichever member of their technical staff was closest, but no, not Thierry Henry.

The referee had allowed play to continue well beyond the 10 minutes of the allotted additional time and the French manager didn’t like it one bit. Those who know him will not have been surprised. Henry’s sense of what he perceives to be injustice does not need much to be stirred.

“It there is one thing which drives me, it is anger,” he had said when he was still one of the world’s most feared strikers. So nothing has changed, except that it is now close to 10 years since Henry last played in a competitive match.

He is now 46, the same age as Gareth Southgate was when he took charge of England for the first time. He is doing the job he had always known he would be doing after his playing career had ended, which is not to say things have gone according to plan since. His desire to join Arsenal’s first-team coaching staff was thwarted by Arsène Wenger, despite what they had achieved together and Henry’s mentoring role at the club’s academy; so he pursued his coaching education with Belgium, working as Roberto Martínez’s third, then second in command, when he earned the praise of players such as Michy Batshuayi, Romelu Lukaku and Eden Hazard. So far, not perfect, maybe, but decent.

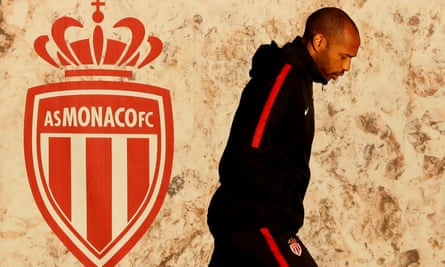

Come 2018, Henry felt ready to go alone and, after turning down Bordeaux, accepted the job of succeeding Leonardo Jardim at Monaco. As Henry knew everything there was to know about the club, it seemed a natural fit. But the key players who had taken them to the Ligue 1 title 17 months previously, Bernardo Silva and Kylian Mbappé, had gone and it showed.

Henry lasted 104 days, leaving with a record of two wins in 12 league games and a reputation in tatters. His inability to stomach criticism had soured his relationship with the French media from the outset and the way he publicly remonstrated with his players when they made a mistake only reinforced the image of a haughty prima donna who found it impossible to communicate with lesser mortals when things didn’t go the way he wanted.

No club offered him a chance to bounce back after such a disaster. It was only when his advisers approached the MLS franchise Montréal off their own bat that he was able to resume his managerial career.

Then Covid struck, which hit him particularly hard, as he had to go through the lockdowns and restrictions away from his family. It was back to square one, again. Yet here he is now, one match away from an Olympic final.

Some will say Henry only put his name forward for the post of manager of France’s Under-21s and Olympic team because no one else would have him. One thing is sure: it wasn’t for the money. He earns the same salary as his predecessor, Sylvain Ripoll, less than a third of what the manager of a middling Championship club would expect to be offered, and a 10th of what Sky Sports was rumoured to pay him for his punditry.

after newsletter promotion

Nor was it an easy way to earn back some credit, given France’s prodigious reservoir of young talents. The proximity of Euro 2024 meant that eligible players such as William Saliba, Bradley Barcola, Warren Zaïre-Emery and Eduardo Camavinga could not be selected. Neither could he call on the best of the under-19 team, which lost the European Championship final against Spain a few days ago.

Henry had a lot to lose if it didn’t work out this time. He also has a lot to hope for – and not just a gold medal. Didier Deschamps cannot carry on forever, can he? Since Michel Hidalgo retired in 1984, the French federation has stuck to a two-pronged strategy when picking a new national team manager, the exception being Jacques Santini from 2002 to 2004.

The recipient could be a former international of global stature, as Michel Platini, Laurent Blanc and Deschamps indisputably were. If not, he would be promoted from within. Gérard Houllier was Platini’s assistant; Aimé Jacquet was Houllier’s right-hand man; Roger Lemerre had sat next to Jacquet on the bench. A variation on that theme was to pick whoever did well in charge of the Espoirs, as Raymond Domenech – yes, Domenech – had done when taking them to the final of Under-23 Euros in 2002.

More to the point, the late Henri Michel had been appointed on the back of the Olympic gold medal his team won in Los Angeles in 1984. With Zinedine Zidane’s interest in Les Bleus reportedly cooling, there will not be a plethora of candidates who can tick the FFF’s boxes when Deschamps calls time, which might be in 2026, one year after Henry’s own contract expires, and when the Monaco disaster will be but a distant memory.

Source: theguardian.com