G

Ail Emms delivered a presentation at her school about her mother, Janice, who played for the English team at the 1971 football World Cup in Mexico. However, her classmates did not believe her. They found it hard to believe that a 19-year-old Janice Emms had the opportunity to play in front of 90,000 spectators at the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City and stayed at the same hotel as the 1970 Bobby Moore team. They dismissed the idea that her team needed police escorts to handle their fame and brushed it off as a made-up story. According to them, there was no such thing as a women’s World Cup. They demanded proof in the form of pictures.

Gail Emms, a badminton world champion and Olympic silver medallist, faced challenges in getting recognition for her mother’s accomplishments. Despite her own success, Emms had been advocating for her mother’s achievements at the Mexico Olympics for years. However, it was difficult to convince people due to the lack of easily accessible information on the event at the time.

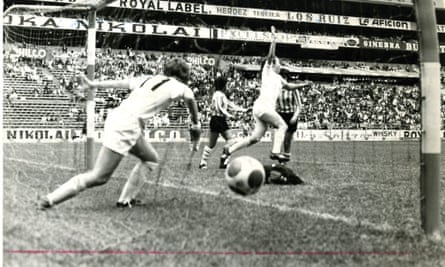

In this month, the evidence that was missing has now been uncovered, in all its vibrant hues and lively fan noise. Copa 71 is a documentary that recounts the tale of the groundbreaking tournament through the perspective of the players who participated in it. The film includes never-before-seen footage of matches that were only shown in Mexico. For Emms, it was her first chance to see her mother wearing an England jersey – “oh my God, there she is, leading the attack and dominating the goal!” – and for football, it marks the revival of one of the most significant moments in the history of the sport.

For all the records broken at last year’s Fifa Women’s World Cup, the unofficial tournament staged 52 years earlier remains the best attended in the sport, something Carrie Dunn, – whose book, Unsuitable for Females, describes the history of the women’s game in England – is keen to emphasise.

Display the image in full-screen mode.

Dunn stated that following Barcelona’s semi-final in the Champions League, several experts claimed it was the largest crowd at a women’s football game. However, this statement is not accurate. Many view women’s football as beginning in 1991 or with the 1999 World Cup final featuring Brandi Chastain, but there is a rich and significant history that is often overlooked. This history includes pioneering women whose stories have not been given proper recognition.

The 1971 Women’s World Cup was a combination of a miracle and a volatile situation. During this time, female footballers could only hope to be ignored rather than face ridicule and abuse. The FA had recently lifted a 50-year ban that had prevented women from playing on their grounds and using their facilities. Other countries were still following England’s discriminatory actions, and in Brazil, it was actually against the law for women to play football due to martial law.

Despite the unfavorable conditions, a team of television executives recognized a chance. They had been inspired by an international competition in Italy the year before, which showed them the profit potential of organizing an event that combined two of men’s greatest passions: soccer and women. In August and September, their World Cup would feature five teams – England, Argentina, Italy, France, and Denmark – along with the host country Mexico. A highly effective marketing campaign bombarded the media with enticing stories and enticed audiences with gimmicks like pink goalposts and temporary beauty salons – although these tactics were rather cliched.

Display the image in full screen mode.

In the movie Copa 71, produced by Serena and Venus Williams, there is a particular scene that showcases the success of the event’s marketing. The young England team arrives at their destination and are greeted with a frenzy of camera flashes, leaving them wondering who could be on their flight (spoiler alert: it’s them). The documentary sheds light on the stark contrast between the players’ celebratory treatment during the tournament, both on the field and on Mexican talk shows, and the harsh reception they received upon returning home. One of the reasons the team kept quiet about their accomplishments was due to the FA’s decision to issue playing bans for participating in an “unsanctioned” competition. According to Dunn, this caused the younger players to feel like they had done something wrong, leading them to not even discuss it amongst themselves.

In 2019, the BBC brought the team back together on The One Show and called them the “Lost Lionesses”. Their tale is heartwarming – after years of not being in contact, they now have an active WhatsApp group where they share memories and more. However, this is just one aspect of a captivating tournament that involved controversial refereeing, payment disputes, player strikes, and on-field violence. Despite England’s early elimination in the group stages – losing 4-1 and 4-0 to the more skilled Argentina and Mexico teams – the knockout round provided one of the most remarkable and scandalous World Cup moments in history.

In the second semi-final, everyone was focused on Elena Schiavo, a 23-year-old Italian player known for her powerful right foot and intense temper. With Mexico leading 2-1, Schiavo scored a incredible free kick from about 10 yards to the right of the penalty area. However, the referee immediately disallowed the goal. This was the second time the referee had disallowed a goal for Italy, causing a heated argument and a fight on the field.

David Goldblatt, the writer of The Ball Is Round: A Global History of Football and the only male contributor in Copa 71, believes that if there had been more female football journalists, the story would have been widely shared. He also believes that the football community missed a valuable opportunity with Schiavo. Goldblatt sees her as a potential trailblazer akin to Roy Keane, with her sharp observations and assertive demeanor.

He thinks it is vital for the women’s sport to have a renewed recognition and value for moments like these. “Football is the only widely-liked setting where I have seen people chant ‘Terrible team, no past’. Each game played today holds significance, at least partly, because of its role in a bigger story and women’s football has been lacking in that aspect. Many significant events occurred between the Dick Kerr Ladies in World War 1 and the 1991 World Cup, but these stories were not being shared, and some are truly legendary.”

“According to Dunn, the history of women’s football has not been well-documented until recently. It has been a challenge to piece together information since there were no official tournaments or professional leagues, and records were not kept in an organized manner. There is a common belief that all the necessary paperwork exists somewhere, but its exact location remains a mystery.”

Display the image in full screen mode.

The documentary’s themes of power, control, misogynistic officialdom, and commercial opportunism also resonate strongly in the wake of last year’s Fifa World Cup – and at a time when women’s football is attracting more investment than ever before. “It just proves that football fever has been simmering in the world’s female population for the last 120 years like lava beneath the crust of the earth,” says Goldblatt. “Given any kind of chance, there it was waiting to explode. Isn’t it great finally we’ve got there?”

The reappearance of footage from the 1971 World Cup has helped players remember forgotten moments, such as Paula Rayner (now Milnes) scoring against Argentina in England’s first game. The documentary allows them to share their incredible experience with an audience who may have never thought it was possible.

Emms is grateful for the opportunity for future generations to show their gratitude, as her own athletic journey was inspired by her mother.

“They bravely traveled to Mexico, defying all opposition and boldly standing up to Fifa,” she remarks. “It’s truly wonderful to honor that accomplishment. It wasn’t just a fantasy, it was a reality.”

Source: theguardian.com