The Bentley was not on the driveway. By now, after nine months of protests, the Southend United fans knew that meant Ron Martin wasn’t home. Martin is the chairman of Southend United FC, and his almost 25 years in charge are widely seen – both by fans and more dispassionate observers – as one of the most disastrous chairmanships in modern football. Since 2007, Southend have sunk from the English game’s second tier, the Championship, down to the third and then the fourth. In 2021, the club fell out of the league entirely for the first time in its history. At this final indignity, a plaque at the Blue Boar pub, which marks the site where the club was founded in 1906, was painted over with the letters RIP.

On the late September day I attended, about 40 or 50 fans were amassed on the pavement outside Martin’s residence. A large coniferous tree dwarfed the two security guards who idled on the driveway. When fans had started protesting outside Martin’s house in early 2023, a few brought bags of beer as if it was an away day. The organisers, Southend Fan Protest Group, soon put a stop to this. If they were serious about their objectives – summarised by their banner, “ENOUGH IS ENOUGH. PAY UP. PACK UP. SELL UP” – they needed to do it properly. They replaced the cans with flyers, and their cause picked up more supporters.

Most attenders were not natural born protesters, and the atmosphere was one of subdued duty. Some fans attempted to lighten the proceedings. One arrived with boxes of cupcakes, each with “Martin Out” piped in white lettering. Another protester, whose first Southend game was a 1-1 draw against Aldershot Town in 1967, was dressed as a clown.

A month earlier, Martin had been summoned to attend the high court over an unpaid £275,000 tax bill. It was the 18th time since 2000 that he had been called in by HMRC to explain why the club had missed the deadline for payment. Judge Sebastian Prentis said that Southend United would be wound up if they missed the new, final payment deadline of 4 October. “If this was not a football club, with the attachment of its fans, I would be winding it up today,” he said. “This has got to be sorted out.”

Southend were deducted 10 points by the National League for missing the August deadline, leaving them rooted to the bottom of the table. Two days later, on 25 August, their match against Eastleigh was interrupted by protesting fans who threw tennis balls on the pitch, along with plastic rats, a nod to Martin’s nickname, Ron the Rat. Some fans had taken to singing, to the tune of Rotterdam by the Beautiful South: “Martin’s a wanker everywhere he goes, Martin’s a wanker everywhere he goes, everywhere he goes.”

That the club was mismanaged and broke was nothing new. Previous chairmen had faced fan protests. But the decline under Martin had been longer and steeper than ever before. Under Martin’s tenure, staff wages had often been paid late or missed altogether, and there were regular threats that the club would be wound up.

To fans, the club’s long-term financial woes contrasted sharply with Martin’s lifestyle. His helicopter trips to Ascot had come to symbolise his seemingly lavish lifestyle after a photo circulated on the fan message board, ShrimperZone. “I probably see him three or four times a week and he’s always smirking,” said a 25-year-old fan who told me his name was Harry, when I asked if he ever caught sight of Ron during his regular protest visits. “You think, you ain’t paying your staff, mate, who the hell do you think you are?” Harry had been a Southend fan all his life, ever since his dad first took him as a boy. Like many fans, his anger seemed to be the product of unrequited love. He had given the club so much; in return, the club – or at least its owner – had consistently broken his heart.

You could say that Martin had finally started listening to his critics: he had finally put the club up for sale in March 2023. One potential suitor, a local firm called Kimura, had pulled out during the summer. All hope now rested on an “Australian chap” mentioned by Martin in the high court in August, who he said wanted to buy the club. But by now Martin had said a lot of things. Fans weren’t getting their hopes up.

Outside Martin’s house, the security guards kicked their feet in the shingle drive, hands in pockets, waiting for the moment they could leave and get on with their weekends. At roughly 12.30pm, the supporter dressed as a clown removed his nose and headed home.

Before Ron Martin owned a football club, his biggest sporting claim to fame was that, as a young man, he was part of the British bobsleigh team. He went to the 1980 Winter Olympics as a squad member, but he had no love for the sport: it was too cold, he once said. Fans claim Martin has little fondness for football, either. Although he denies this today, in an interview in 2000 he said he was “never a massive football fan” before he got involved with Southend.

Martin came to the club via a property deal. In 1998, his company joined with a property development firm to purchase Southend FC and its stadium, Roots Hall, for £4m. The new owners, trading as South Eastern Leisure (SEL), immediately split Roots Hall from the football club – creating Roots Hall Ltd – and started charging the club £400,000 a year rent to use it. When the chairman, John Main, was sacked in 2000, Martin installed himself in the role. At the time, Main spoke to the journalist David Conn about his concerns over the potential conflict of interest that Martin’s chairmanship brought with it – a businessman whose primary concern was profit overseeing a cherished community asset – and pointed out that the rent could “cripple” the club in the future. “How can he argue for the club, particularly against SEL, if he jointly owns SEL and his main interest is in making money from the property deal?” wondered Main. Today, 24 years after Main’s comments, Martin says he has always wanted what is best for Southend United.

From the start, Martin’s ambition was to move the club to a new stadium, which would be built on an out-of-town site known as Fossetts Farm. This was the only way to make Southend United competitive in the age of the Premier League, he insisted. But to fans, Southend’s ground, Roots Hall, was more than just a fungible asset – it occupied a special place in local history. “If there is a monument to the British football supporter, it is Roots Hall, for here is a ground built almost entirely through the efforts of a small, but dedicated group of people,” wrote Simon Inglis in his peerless compendium Football Grounds of England and Wales. The supporters’ club raised the vast majority of the construction costs themselves. The building work took five years and, finally, on a bright August Saturday in 1955, with a brass band fanfare and a thumping 3-1 win over Norwich City, it became the club’s home. Seven years later, the stadium’s once-defining feature – the towering South Bank stand, built into a tall slope of the former quarry – was completed.

I first heard the roar of the Roots Hall crowd from my nan’s back garden two streets from the ground. By 1998, when I was old enough to take myself to matches, instead of a tall stack of supporters cheering on the Shrimpers, I used to look over at two squat tiers of fans: the then chairman Vic Jobson had sold off much of the South Bank stand to a property developer in the late 80s. In the late 90s, there was an air of apathy after consecutive relegations, but in the following decade, the club briefly climbed back up to the Championship. In November 2006, Southend played Manchester United in the League Cup. Unbelievably, they won – beating a team that included Wayne Rooney and Cristiano Ronaldo – 1-0 thanks to a sublime free-kick from 25 yards out. For many fans, it remains the greatest day in the club’s history. (Many still boast of Southend’s 100% record against Man Utd, this being the first and only time the two teams have met.)

After a period of relative success, the fans were left hopeful for more – and Martin convinced the majority that the only way to achieve that was to leave Roots Hall. The first planning application for Fossetts Farm was made in 2000, but it wasn’t backed by the council until January 2007. It was to be a 22,000-seat stadium that would include hotel and conference facilities, restaurants, shops and residential buildings. Fans packed the council’s public gallery and sang with joy after 13 of 16 committee members voted for the move. When Martin appeared outside the chamber where the meeting had been held, they started singing in unison: “There’s only one Ron Martin.”

That euphoric feeling did not last.

Years passed and no new stadium was built. Meanwhile, the old one decayed. Various reasons have been given for the failure to build the club’s new home: planning issues, the 2008 crash, multiple relegations, halts to construction owing to the discovery of a bronze age burial ground. Despite the setbacks, Martin seemed undeterred. In 2021, after years of false starts, he enlisted the architecture firm that designed the 2012 London Olympic Stadium. After various changes of plan to try to recoup profit, its latest Fossetts Farm design – complete with 224 flats built into the side of the new north stand – looks like the sort of thing an AI imaging app might throw up if you typed in “property developer football stadium”. Some fans balked at the symbolism: was this a stadium for the fans or a property development with football ground attached?

Martin liked to say he was a property developer, but his business wasn’t really development, per se, but land: banking it, letting it appreciate in value, then selling it for profit. “I think he believes he loves the club – but he doesn’t,” said Clare Campbell, a board member of the Shrimpers Trust who works behind the bar in the Railway pub, which relies on matchdays for the regular custom. “It’s always been about Fossetts Farm; it’s always been about money for him, I don’t think he understands anything else.”

By the start of 2023, Southend’s predicament was by no means unique. The fans of Reading FC, a League One club that was in the Premier League a decade ago, were running their own protest movement against their owner, billionaire Chinese tycoon Dai Yongge, after receiving multiple winding-up orders in a matter of months. Scunthorpe United in the National League North started 2023 with the threat of being wound up before being saved by a local businessman, David Hilton, only for his own tenure to spiral out of control, as staff went unpaid and an investigation by the Athletic in September 2023 revealed that in 2015, under a different name, he had been sentenced to two years in prison for 15 counts of fraud.

On the pitch, despite moments of joy, the prevailing trend has been one of steep decline. “Every conversation you have is negative; every game you go to is negative; every notification on your phone is negative,” said Chris Phillips, the chief sports reporter for the local newspaper, the Evening Echo, who started supporting Southend when he was seven.

Relations between fans and chairman reached new lows in the 2021/22 season, after the club’s relegation from the English football league. At one away game, as Southend toiled to their fourth straight defeat, Martin took umbrage at the fans chanting against him and left the director’s box to confront them. The fans threw a volley of expletives and at least one hotdog at him. At the next game, on 6 October, fans held up protest banners and invaded the pitch at full-time. Two days later, Martin poured more fuel on the flames during an online fan meeting. Asked why he didn’t just sell up, he replied: “Because I fucking love the club, you idiot. That’s why.”

For years the Southend United fanbase had been known to raise only an apathetic grumble at the side’s mismanagement, but now more and more were willing to join in, as it became clear the club was under existential threat. In a sense, the club’s current fortunes mirrored those of the city itself. It is a place that houses pockets of absurd wealth made in the City of London alongside neglected high-rise flats long earmarked for demolition. A Local Government Authority report in 2022 highlighted Southend’s “entrenched inequality and deprivation”. Many of its civic centres and institutions are dying or dead. The seafront is still lively on a sunny bank holiday, but much of the nightlife Southend was once known for had long left town, while the jewel in the crown of the golden mile, the Kursaal, a Victorian amusement park and ballroom – owned by the UK arm of an American investment firm with a 200-year lease – has been closed for years.

To some fans, the fate of Southend United had become not just a symbolic battle. If it could be pulled out of impending disaster, they hoped that other turnarounds might be possible.

Lining the perimeter of Southend’s training ground are stacked rows of rusting metal structures that once constituted a part of Martin’s plans for success. In 2014, Martin paid £460,000 for the London Soccerdome, originally built to serve the David Beckham Academy in Greenwich, south-east London. Martin had it floated down the Thames on a barge, with plans to reassemble it in Southend, where it would provide world class, all-weather training facilities for academy players. The only snag was that it would cost millions to erect and maintain, and so it never was. Today, it is covered in thick spools of weeds and brambles, an Ozymandias-like monument to the wastefulness of the Martin era.

When I visited the training facilities in October, a similar feeling of listlessness prevailed. Water leaked into a bucket in the gym. Thick black mould had formed above the heads of players in the changing room. Many managers would have walked away long ago, but Kevin Maher had decided to stay and front it out. He apologised that the lack of running water meant he couldn’t make me a coffee.

Maher was a club legend even before he became manager: as a player, he had made 450 appearances, captained the side, and played in the Manchester United win. He told me that when he arrived back at his old training ground in late October 2021 he “could smell the fear in the building”.

He was hired by Southend United’s CEO, Tom Lawrence, a bear of a man who smiles so disarmingly it feels as if he could save a football club on vibes alone. “We’ve been ducking and diving,” said Lawrence as we sat in Ron Martin’s office – which is now his office, as Martin no longer comes to Roots Hall. “We’ve had the MP coming in one door and the bailiff going out the other.”

Raised a little way up the coast in Essex, Lawrence grew up supporting Southend. When he was hired in the weeks following Southend’s relegation in 2021, he attempted to bring order to the chaos all around him. “The old accountant used to phone up and say: ‘Ron, I need 80 grand’, or: ‘I need 200 grand.’ And sometimes it was there, and sometimes it wasn’t,” he told me. Lawrence devised a new business plan and the club hired Maher as manager.

As ever with Southend United, things were looking up, until they weren’t. No sooner had Maher got his feet under the table than HMRC came knocking again after another missed deadline. In December 2021, the club was given a transfer embargo, meaning it could not sign any new players. “The business plan got shoved to one side and it was, right, who are we fighting today,” said Lawrence. He began to lose count of the number of hearings the club had had with their energy supplier, N Power, for failure to pay their bills. There were times before evening matches where he would worry they wouldn’t be able to turn on the floodlights.

Even though Maher and the players soldiered on, they were no match for the forces of decline. In July 2023, the water was turned off in the training ground. Players couldn’t use the toilet facilities or shower after training. Maher and his assistants, Darren Currie and Mark Bentley, took it in turns to stop at Aldi to pick up pre-made food and bottled water as they couldn’t use the kitchen facilities. In the end, to restore the water, Lawrence resorted to ordering a huge silver water tank, which was dropped off in the car park and installed for free by a supporter who also happened to be a plumber.

There wasn’t the money to do anything properly. Even when there was money, local businesses sometimes refused to trade with them because the club still owed them. At the start of this season, the groundsman, Chris Ball, had to borrow a lawnmower from Premier League side Tottenham Hotspur just to cut the grass at Roots Hall. “We are just doing the bare minimum just to get us through. It’s just like a survival battle,” Ball told me when I met him in November. But these trials also brought a sense of real purpose. “I think I secretly enjoy it, otherwise I wouldn’t do it,” said Ball. Keeping the show on the road, the fans coming through the turnstiles, the bars stocked and serving and the pitch surface playable, felt nothing short of miraculous.

Out of necessity, Lawrence rolled his sleeves up and got stuck into jobs many might think beneath the CEO of a football club. (Although fans had turned on Martin, they generally recognised Lawrence’s efforts to keep the club going.) He loaned money to unpaid staff to help them survive and personally paid for the petrol in the team bus when the club didn’t have the funds. Last summer, when the club was told by the council that the stadium was at risk of not receiving a safety certificate – a requirement for all sports grounds over a certain size – Lawrence learned how to use a cherrypicker and an angle grinder to chop out rusting metalwork, and climbed into the stadium’s lofts to help fireproof it.

Safety certificate or no, Roots Hall was a mess, having gone without any professional cleaning for months. Lawrence turned to the fanbase for help, and on a sunny Sunday in late July, a week before the first match of the 23/24 season, in a show of deep love for the club that had provided them years of pain, 150 volunteers came to Roots Hall to clean the seats of pigeon shit, sweep the floors, paint walls, reattach doors to hinges.

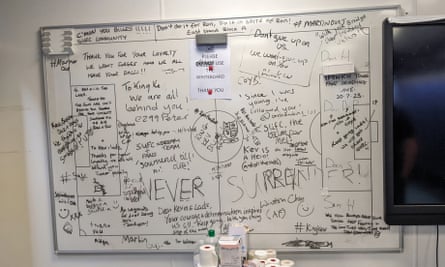

Fans helping clean the stands had to go into the home team dressing room to fill up their buckets with water, and some wrote messages of support on Maher’s tactics board: Legends for just being here – thank you … We won’t forget you and we all have your back … Don’t give up on us – we won’t give up on you. Months later, Maher still seemed moved when he relayed the story to me: “That’s not something I plan on wiping down any time soon.”

While fans had lost patience with the Martin regime, the resurgence in spirit on the pitch seemed to galvanise local support. Some boycotted home games – not wanting to give Martin their money – but others returned. When I started going in the late 90s, the average attendance at Roots Hall was about 4,000; this season, it was pushing 6,000. The absence of football during the pandemic and the ongoing uncertainty about the club’s future had brought home to fans just what they would miss if the club disappeared for good. There was still something magical about Roots Hall, a shambling grandiosity in its rusting corrugated iron and majestic floodlights that illuminated the pitched roofs of the suburban street that ran behind the west stand.

And then there was the simple fact that matchdays offered a social occasion, a reason to gather, a community. Colin Hall, whom I met at the protest outside Martin’s house, told me he had moved to Southend with his wife after he left the army. He hadn’t known anyone in the area, so the fans became his network. Eventually, Colin and his wife separated, but he stayed married to the club. He had been coming to games with his daughter, Lucy, since she was seven years old. She was now approaching 18, and still travelling to most away games with him.

By the 23/24 season, the Railway and Blue Boar pubs had become protest bases. Fans’ general unrest had evolved into regular protest: before matches they marched to the beat of a drum through the heart of the city from Southend pier to Roots Hall. After a decent run of form at the start of the season, the transfer embargo began to bite, as the threadbare squad was worn down by injury and exhaustion. In mid-September, Southend lost 3-0 at York City and two players were sent off, exacerbating the side’s personnel issues. The match had to be stopped when fans stormed the pitch. It felt like the clock was ticking on the club’s very existence. Nathan Ralph, the club captain, confirmed the match felt like a crossroads. “There was a lot of anxiety,” he told me. “Naturally it will filter its way to the team.”

The date of the club’s final HMRC hearing, 4 October 2023, was a little more than two weeks away. Rumours were swirling that Martin was negotiating with the Aussie he had mentioned in the high court, but fans were wary of hope. “He’ll drag us down with him,” said Lee, a protesting fan I met outside Martin’s house. There were times, during these weeks, when players would park their cars at the training ground and wonder whether this could be it, their last week as a professional footballer for Southend.

In the weeks before the final showdown at the high court in early October, Southend United’s in-house medical team advised Lawrence to make a contingency plan to assist fans’ mental health should the club die that day. The fanzine All At Sea printed its September issue in black. At the protest outside Martin’s house in September, a fan in his 80s who had been watching Southend play since 1966 told me it was pure desperation that had brought him out here on to Martin’s doorstep. His voice wavered when he told me what would be lost should the club go under. It was as if the death of Southend United might leave an actual, physical hole in his heart.

On Tuesday 3 October, the evening before the hearing, Southend were playing Oxford City. Just a few hours before kickoff, supporters still didn’t know whether or not the game would be Southend’s last. Expat fans flew in from Spain and France to see the Blues one last time; some of those boycotting the club in protest against Martin’s tenure broke their self-imposed ban. National news journalists were dispatched to cover.

By 4pm there was still no news of how the at least £275,000 in debts were going to be paid. Fans twitched at their phones, checking social media and the ShrimperZone forum. “Woke up this morning with a nasty headache from a restless night. My heart can’t take much more,” said one.

Finally, at 4.42pm, came the moment they were praying for, when reporter Chris Phillips posted on X: “Fantastic news from Roots Hall.”

The Australian was real, and he had come to save the club.

The first time Justin Rees told his wife, Tjinta, that he wanted to buy a small football club 10,000 miles from their home, she cried. “Our plan was to open a hotel and wedding venue, have two girls and a dog and live in Bondi and then live happily ever after,” Rees told me. “But I obviously threw a hand grenade at those plans.”

A few years earlier, just before his 40th birthday, Rees had made a lot of money selling the IT consulting company he co-founded, having grown it from five staff members to more than 100 in a few years. Since then he had been kicking about looking for something to do. The idea of investing in a football club had been in the back of his mind ever since he watched the Disney+ show about actors Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenny buying the Welsh side Wrexham, and helping them climb up the leagues with a healthy dose of cash and some Hollywood pizazz. Then one day last summer, Rees noticed an item on the BBC News app. It said that Ron Martin’s 70.6% stake in Southend United was available for just £1, plus a few million in debt.

Rees was intrigued. He had grown up in the western fringe of Greater Sydney, but his dad, an Englishman with a fervent passion for Queens Park Rangers, had passed on a love of the nitty-gritty of the English game. As a young man, when Rees fired up the highly addictive football video game Championship Manager, he would choose to play not as a Premier League giant, but as Southend’s non-league local rivals Dagenham and Redbridge.

In July, Rees started to make inquiries about Southend. He came to games undercover to get a feel for the club. (His first match was an away game at his old favourites, Dagenham and Redbridge.) He was impressed by the core of the club: Maher, Lawrence and the club’s veteran head of football, John Still. Later that month, he flew over to meet Ron Martin and his son Jack, who handled the property side of things.

Rees wanted in, but he didn’t want to do it alone. He attempted to assemble a consortium of businesspeople who had emotional links to the club (and, of course, money to invest). His strategy wasn’t fancy: he sent a BCC email to as many names as he could to see how many might be interested. The answer, at first, was zero. “He told us how much debt we was in,” said John Watson, the boss of a local taxi firm. “I said, I love this club, [but] what on earth are you doing, you must be absolutely bonkers. He said, stop being a pussycat, I’ll mark you down as a maybe.” Watson started to think about the good times he’d had watching Southend for the past 40 years, phoned back and decided to join up.

Rees eventually assembled an eclectic group of 10 cashed-up Southend supporters: a mortgage broker, hedge fund manager, the son of a local MP. He said he liked the fact that the club wasn’t being bought by a nation state or American private equity. “Nothing wrong with that money, but I felt like it needed to be a Southend story. A bunch of football fans sharing the load,” he told me. They became known among fans as “the consortium”.

Martin and Rees had agreed the principles of the deal already, but by the Friday before the 4 October hearing, Rees wasn’t confident a deal could be done. He still needed the creditors – a collection of large and small companies owed money for unpaid bills – to reduce their debts to a level the consortium felt it could pay. Lawrence flew out to Marbella to meet one of the creditors to try to persuade them to do the club a favour. Over the weekend, the scale of the task dawned on Rees. But rescuing a club like Southend United was too romantic an idea to resist. “I think football has lost its way – the money, the clubs going under,” he said. “Southend became a wonderful snapshot of a club that existed quite happily for 117 years and then through mismanagement has gone off a cliff.”

Rees saw it through, taking a bigger stake than he wanted to make up the shortfall, and reached a basic agreement with Martin on 3 October. The club was saved, and the pubs filled with fans unsure what to make of a new and unfamiliar feeling: optimism.

I contacted Ron Martin in late September to ask for an interview, but he didn’t want to meet before the hearing had taken place. So, on 5 October, I waited in the lobby bar of a mildly ostentatious business-tourist hotel in Aldwych, central London. His previous engagement had overrun and so he arrived with a hurried and apologetic air. In person, he was a subdued and slightly shambling figure, softly spoken, reticent, rather than the domineering, gangsterish presence of lore.

Perhaps it was understandable. The Fossetts Farm project he had fought for had not happened, and 25 years had gone up in smoke. When I asked Martin what he thought his legacy might be, he said “keeping Southend alive”. (“On life support more like” said one fan, when I relayed this later.) “I don’t suppose, to be perfectly frank, I’ve done myself any favours by the number of times we’ve had petitions, but sometimes it’s liquidity,” he said. “There was hardly a year when Southend United made ends meet.”

Did he feel remorseful over staff not being paid? “If the pot is dry, what do you do?” he replied. “The staff have been fantastic, they have been hugely supportive.”

Martin reached around for a reason the club had been in such dire straits. “Double relegation on the back of Covid is what killed us,” he said. But, as fans have pointed out, surely Martin had some responsibility for the club he runs being relegated in two consecutive seasons? “Football,” said Martin, “is different from every other business. It’s like having a tiger by the tail … trying to manage it.” The more Martin spoke, the more I began to think that he actually enjoyed wrangling with this tiger. Despite the mess he had left in his wake, he did not regret getting involved with the game. “We have had some passionate, fantastic times over 25 years,” he said, sounding like a man taking the positives from a bitter divorce.

A couple of weeks later, when we spoke on the phone, I asked Martin whether he would have been a richer man today had he not owned a football club for the past 25 years, he replied, “Oh, Christ, absolutely – massively.” He struggled to calculate a figure, but eventually said it was more than £30m. He said some of it was rent for Roots Hall that had been charged to the club and never been paid – “probably about 12 or 13 million” – and the rest was capital he had pumped into the club to keep it afloat.

He assured me that he was always going to write off the debt the club had built up due to its unpaid rent (although he still invoiced for it). “I’m not going to blow my own trumpet, but I have been kind to the club,” he said. As further evidence, he noted, “I could have put it into administration any time. Hand the keys to the receiver and let him run the club.”

I asked whether he thought this attitude – that the club was his to either rescue or dispose of – might be at the heart of his conflict with the fans. “Every board should listen to what the fans have to say, but where do you stop, putting fans on the board?” Martin said, with a slightly withering tone. “I mean there aren’t many successful clubs run by a fan group, are there?”

You could argue Bayern Munich are quite successful, I said.

Martin laughed down the line and acknowledged the point, before returning to his position. “But generally speaking, when push comes to shove, somebody has to put their hand in their pocket.”

In the weeks following the reprieve in the high court, the excitement around Justin Rees only grew: to many fans, the Australian had already achieved messiah-like status, and he practically levitated into Southend for his first home game, against Solihull Moors on a Saturday in late October.

Pre-match, inside the Blue Boar pub, Rees met some of his fellow members of the consortium for the first time, calming whatever nerves he had with a few pints. The landlady, Michele, gifted him a scarf complete with Southend United crest, Australian flag and “G’day mate”, which he wore for the rest of the day. Fans asked Rees if they could have a selfie with him and he duly obliged, shaking hands, sharing jokes. Southend had begged for a saviour, and who was he to disappoint?

Even so, Rees was careful to temper expectations. “I’m not a Hollywood star and this isn’t Wrexham,” he told me. “I believe that a football club shouldn’t be dependent on its owners; they shouldn’t celebrate them when they succeed and it shouldn’t be all their fault when they fail. And the only way you can back that up is financial sustainability.” The two main priorities for the next five years would be fixing the stadium and returning to the football league.

By kickoff, there were almost 7,000 fans at Roots Hall, the biggest crowd of the season, and the sun was dutifully shining. Suited executive staff shimmied through the narrow corridors behind the directors’ box with a new vigour. Out on the terraces in the west stand, the same fans who had chanted “Martin’s a wanker” were now locked in a fulsome rendition of Bob Marley’s Three Little Birds: “Don’t worry about a thing / ’cause every little thing is gonna be all right.” On the pitch, Southend strolled to victory, winning 5-0.

In Rees’s executive box after the game, it was standing room only. Bottles of Peroni and Amstel were handed out. The local MP, Anna Firth, was there to welcome the potential new chairman. Rees seemed hyped and giddy, like a gambler in full flow, when the night was still good and the chips had not yet fallen down. As he hollered out of the hospitality suite to catch Maher’s attention – “Kev! Kev!” – he reminded me of an ageless frat boy. “This feels like a life hack,” he said as we watched Southend through the window, envisioning beer-soaked weekends away.

After the match, some of the consortium took Rees down to one of Roots Hall’s many bars, where he ran into a male fan dressed in a kangaroo onesie. Later, they went from pub to pub, Rees talking to fans and posing for more pictures, until the night began to blur. All he knew for sure, Rees told me later, was that he was in a kebab house at 3am, and the fan in the kangaroo onesie was still with him.

On that sunny Saturday against Solihull, it seemed the tide had already turned. But over the following weeks, negotiations over the deal dragged on and on, with no apparent progress. Fans started to get nervous. And then, just before 3pm on 23 December, as Southend were about to play Kidderminster Harriers, when many fans had given up hope, came a formal announcement: “The Club is pleased to announce that Ron and the Consortium have today exchanged contracts for the sale of Southend United.” As they read the news on their phones, some fans were in tears. Rees had been on the same train as a lot of them, and had bought them beers in Birmingham before they got the last leg to Kidderminster.

The consortium paid to have the transfer embargo lifted so Kevin Maher could bring in much-needed reinforcements. Maher was given the freedom of the city of Southend for sticking with the club, and the team went on an improbable 15-game unbeaten run.

Yet as time ticked on, final details remained unresolved. The broad agreement was that Martin would keep Fossetts Farm and build 1,300 residential homes there while the club would stay at Roots Hall, which would undergo major renovation. The deal hinged on Martin agreeing to fund the rebuild of Roots Hall, with £20m taken from profit made by the residential development at Fossetts Farm. Contracts had been exchanged, but finalising the deal still depended on the new Fossetts Farm project being approved by the council. Meanwhile, the consortium found themselves in the strange position of paying player and staff wages without having the keys to the club. By January they had spent £2m; come April it was £3m, and the council still hadn’t given the Fossetts project the green light.

In early April, before an away game at Wealdstone FC, in north-west London, I caught up with Colin Hall, whom I had first met outside Ron’s house back in September. We chatted in a Wetherspoon’s, where some travelling fans had taken up temporary residence, before walking to the game through suburban streets lined with trees in blossom. He told me that protesting fans had returned to Martin’s at the weekend, but it was last-minute and the numbers weren’t great. “Probably about 12 of us, but it was enough for him to get security.” The fans wanted to keep the pressure on, wanted to inconvenience him, to cost him money until the deal went through. “He’s laughing,” said Hall. “He’s got a third party paying his bills.”

Rees wasn’t able to make it to the Wealdstone match, but I caught up with him a week later at a busy brunch spot in Southend’s fashionable neighbour Leigh-on-Sea. It was approaching a year since he first saw that Southend was for sale, and he laughed at how different his life had become. He was taking calls at 2am or 3am while visiting Sydney, and reading documents through the night. Every month that the deal dragged on was another £200,000 in wages that the consortium had to pay from their own pockets. Ryan Reynolds did not have to deal with this kind of thing in Welcome to Wrexham.

“No matter how many times councillors and Ron tell me ‘Relax everything will be fine’, until it’s done, I will not relax,” Rees said. (“Justin always wants and expects things to be done yesterday,” Martin told me, when we spoke on the phone in mid-April. “I think the council’s due diligence will always take a period [of time].”)

For Rees, the only respite was football itself. He had started playing for a local amateur club, and still went to every Southend game he could, home and away, enjoying beers with the fans, chasing the adrenaline of the possible win. “It’s my highlight of the week,” he told me, sipping his third coffee of the morning. We had to finish our meeting soon, as he had a haircut booked at 10am. He needed to smarten up for a court appearance. The club had been issued a winding-up petition by the law firm that represented them in previous court disputes with HMRC, and so he and Martin were needed in the high court on Wednesday.

As it turned out, the haircut was not necessary. The case was adjourned until the middle of May, although Martin and Rees still attended proceedings together. The consortium made it clear it would not pay the debt, and certainly not until it owned the club. A familiar fog of dread returned. The club owed money. No one was currently willing to pay. Once again, Southend was staring death in the face. Unless the deal between Martin and the council is agreed before mid-May, the club could be wound up.

Fans took to ShrimperZone yet again to type out a by-now familiar gloom. They feared new points deductions, frozen assets, another summer in limbo. “At what point do the consortium decide enough is enough?” wrote one fan in late April. They debated the technicalities of the deal, the council’s responsibilities, the potential timeline. And through it all, there was a steady drumbeat of despair. “I think someone should do a study on the mental anguish all this has caused on so many people,” wrote one fan. Another simply wrote: “When will it ever end! When will he be gone!”

Source: theguardian.com