Seven months ago Englandthe country came the closest yet to entering thermonuclear war over a refereeing decision. When the referee Simon Hooper mistakenly ruled out a Luis Díaz goal at Tottenham for offside and the Video Assistant Referee Darren England failed to correct him, the initial response was heated and only bubbled up from there.

“They said it was significant, that’s very significant,” said Gary Neville on Sky at full time when a Professional Game Match Officials Limited (PGMOL) statement dropped acknowledging “significant human error” in ruling out the goal. “It makes you wonder how many others they’ve got wrong as well,” chipped in Jamie Redknapp.

The next morning, Liverpool released a statement arguing “sporting integrity had been undermined”, the supporters’ group Spirit of Shankly said that “VAR and PGMOL are not fit for purpose” and the club’s former striker John Aldridge alleged corruption. On the Monday, Ed Balls and Susanna Reid discussed the incident on Good Morning Britain and we were spared the public indignation of MPs only because parliament was in recess.

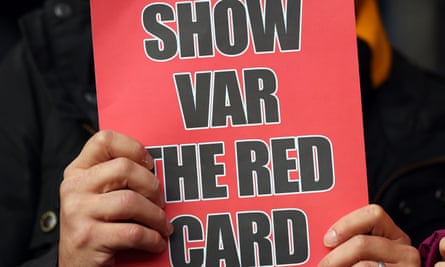

As the season approaches its end and Liverpool prepare to play Spurs again on Sunday, we can look back on this incident as from a different time, but only because frenetic denunciation of referees and VAR is bog standard. This week we learned the VAR Stuart Attwell had got two of three contentious penalty calls correct during Nottingham Forest’s recent defeat by Everton. But that hadn’t stopped Forest stating within an hour of the final whistle that they “could not accept” Attwell’s decisions, had “warned the PGMOL that the VAR is a Luton fan” and were “considering [their] options”.

The Tottenham-Liverpool error was an egregious one and the approach of Forest towards refereeing is particularly combative. The club is so concerned about officiating that it employed the former Premier League official Mark Clattenburg as a consigliere until he resigned on Friday saying his role had caused “unintended friction” with other clubs and he had become “more of a hindrance than a help”. But echoes of these two extreme examples of VAR errors are heard most weeks, be it from managers, pundits or fans. Why is that?

It helps that there is a stream of errors to which critics can attach their ire. Hooper has had a particularly lumpy season, also failing to award Wolves a legitimate penalty in the opening game week, before denying Manchester City a potentially crucial advantage in their 3-3 tussle with Spurs in December, halting play with Jack Grealish bearing down on goal. Even the Premier League’s best referees have had their moments; Michael Oliver, who will officiate at the European Championship this summer, missed a clear penalty foul in the north London derby only last weekend. His boss, Howard Webb, said Oliver would be “disappointed” with his oversight.

However, if you were to take from this that refereeing standards are falling, you would be wrong. According to mid-season statistics shared by the Premier League’s chief football officer, Tony Scholes, standards have never been higher. “Before VAR 82% of the decisions made were deemed to be correct,” Scholes said. “In the season so far, that figure is 96%.” Equally, there have been fewer interventions by VAR this season than last and fewer errors by VAR, including occasions when there should have been an intervention and was not. As one official put it this week, the accuracy of decision-making is higher than Declan Rice’s accuracy of passing, but to many it clearly doesn’t feel that way.

On the TV show Match Officials Mic’d Up this week Webb sought to make the point that not only are refereeing errors human errors, those made by VARs are too. This is a necessary clarification because it’s feasible and perhaps even understandable that people don’t see it that way. VAR is a phrase used not only to describe a person’s role but an entire system and it’s the system that people don’t like.

Multiple camera angles, blue and red lines administered by cursor point, 3D rendering of body parts with offending areas highlighted, the finger pressing on the earpiece. All give the impression of an added layer of complexity having been added to a game beloved for its simplicity. Add to that the life-diminishing lengths of time it can take for a video adjudication to be delivered and for many, especially match-going supporters, VAR has always felt like a counterproductive initiative.

For others, many of whom are inside the game, the change was necessary. With so much riding on the outcome of matches, it was crucial mistakes were eliminated wherever possible. VAR has had great success in eliminating error but it has not been a panacea. This too appears to be a source of abiding frustration.

after newsletter promotion

The PGMOL and Premier League have acknowledged that the experience for fans has not been good enough. To change things, Webb wants to expand communication within the stadium, with the likelihood that from next season referees will be allowed to announce why a decision has been overturned by VAR. Semi-automated offside technology will be introduced at some point next season to speed up decision-making and stop people having to draw fiddly lines (with as yet unexpected problems no doubt produced instead).

That these changes are not in place yet is probably another reason prompting antipathy; improvements in the VAR experience have been too slow in coming. Further adaptations will be as hard to deliver, including the ability to broadcast conversations between a referee and VAR so crowds have a full understanding of what is going on. This is the prize Webb most wants but something the law-making body, the International Football Association Board (Ifab), seems set against.

Communication is a key thread for Webb. It’s what he instituted when successfully introducing VAR to the United States (it helps that it’s a country whose sports are commonly peppered with breaks). It’s what he has achieved with Mic’d Up, an informative monthly show that is effectively clipped up for social media. But he is running to catch up because of a crucial error: the failure on day one to clearly explain what VAR is for.

From one angle it is simple: VAR is there to remove the most consequential errors, those that lead to goals (or no goals), penalties and red cards. But it’s also true that, in England at least, no one wants the VAR to supersede the on-field referee. So we have the dictum that the VAR, other than for offsides, is supposed to engage only in the case of “clear and obvious” errors. But most refereeing decisions contain subjective elements, meaning one person’s clear and obvious error could be another’s marginal call. All this leads to a situation where, in 2024, Jürgen Klopp could say after a draw with Manchester City in which his side had appeared to be denied a penalty: “Isn’t it [VAR] there for making the right decision and not thinking how high a bar you have to overcome to find the right decision?” (The answer? Well, no).

Webb’s task is one not only of communication but of training and upskilling. To that end, PGMOL has sought to promote talented officials up the pyramid, such as Sunny Singh Gill who became the first British south Asian to referee a Premier League match in March. It is also expanding the pool of VAR officials by reaching out to English Football League and Women’s Super League referees. Once appointed these officials receive more training, evaluation and feedback than they did even three years ago. These changes will take time to deliver on the pitch and even then there’s a sense it won’t be enough.

Search “VAR corruption” on YouTube and you will find no shortage of gaudy thumbnails promising conspiracy and outrage. Watch a sports channel or listen to the radio and you will hear similar. A manager’s pre- or post-match press conference too. An apparently simple idea, of using technology to facilitate better refereeing decisions, has turned out to be complex and created a number of unintended consequences. One of those is that the nexus of technology, officialdom and football has proved to be catnip for controversialists, and it may be too late to put that particular feline back in the bag.

Source: theguardian.com