This could have been the ideal farewell – an acknowledgement at the Academy Awards for the exceptional talent of Japan’s unparalleled animator, Hayao Miyazaki.

When The Boy and the Heron was announced as the winner of the best animated feature award in Los Angeles over the weekend, it allowed Japan to pause and consider Miyazaki’s significant impact and question if the 83-year-old is truly done creating films.

The renowned Studio Ghibli, home to Miyazaki’s creative magic for over 30 years, had just earned its second Oscar when discussions about his future arose. While his absence from the 2003 ceremony was said to be a protest against the Iraq War, it is now believed that his recent absence is due to his age and reluctance to travel.

Miyazaki’s deeply personal exploration of the devastating effects of war, The Boy and the Heron, achieved great success at the Oscars. This recognition also made him the oldest director ever to receive a nomination for Best Animated Feature. Remarkably, this was only the second time a hand-drawn animation took home the award, with Miyazaki previously winning in 2003 for Spirited Away.

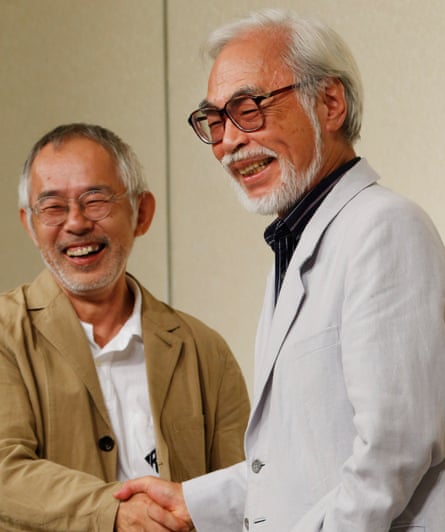

Both Miyazaki and Toshio Suzuki, his longtime friend and producer at Studio Ghibli, were not in attendance at the ceremony. During a press conference in Tokyo, Suzuki expressed his immense joy. Though his partner was not there, Suzuki shared a modest response from the mastermind, who simply deemed the award as “good”.

The idea of completely leaving the company he helped create in 1985 is just as undesirable to the man as it is to his many followers in Japan. A staggering 95% of individuals aged 16-69 in Japan claim to have seen at least one of his movies.

Miyazaki has announced his retirement at least three times to date, only to backtrack once his mind and body had recovered from the exertions of conceptualising and hand-drawing most of the frames in a feature-length film himself.

There are speculations that he may come back to work once more, maybe for a brief animated project. Susan Napier, a Japanese studies professor at the US’s Tufts University and author of the book Miyazakiworld: a Life in Art, believes that he will only retire when he is physically unable to draw. Retirement is not in his nature, as his passion for his work is his top priority.

Rephrased: The looming reality of Miyazaki’s aging poses a risk for Japan’s cultural status. With the global popularity of South Korean culture, Japan may struggle to showcase its own artistic gems without the contributions of Ghibli. According to Napier, Miyazaki is not only a beloved figure in Japan, but also highly regarded internationally. His distinctive and original creations make him irreplaceable and a true auteur.

He will be remembered for creating captivating 2D adventures set in fantastical worlds inhabited by bizarre creatures and breathtaking scenery. His perspective is shaped by his personal history of living through war and the consequent period of economic hardship. Like many others of his age in Japan, Miyazaki holds pacifist views and opposes efforts by conservative politicians to alter the nation’s constitution, which denounces war. In one of his works, The Boy and the Heron, the main character, 12-year-old Mahito Maki, experiences the loss of his mother during the bombing of Tokyo in March 1945, resulting in an estimated 100,000 fatalities.

Miyazaki’s work and his impact are highly adored and appreciated by international audiences, but this is not always the case in his home country. His left-leaning political views have faced backlash from critics. In 2015, his response to a speech by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, in which Abe argued that Japan should not have to apologize for its actions during wartime in Asia, sparked outrage among supporters of Abe. Online far-right activists, known as netto uyoku, heavily attacked his 2013 film The Wind Rises, accusing it of being “anti-Japanese”.

According to Roland Kelts, author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the US, Miyazaki’s dedication to perfection and strong work ethic will likely lead him to pick up his pencil once more.

“He literally doesn’t know how to do anything else, and he’s the very best at the one thing he does know how to do,” said Kelts, who describes Miyazaki as Japan’s “undisputed emissary of anime” among overseas audiences who are otherwise uninterested in Japan. “While he would never say it publicly, of course the accolades and box office mean a ton to Miyazaki. He’s a deeply competitive man, which is one of the reasons Ghibli hasn’t been able or willing to groom a successor.”

Display image in full screen

According to Kelts, Miyazaki was motivated by a desire to surpass the competition, particularly following the success of Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba and Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name. Kelts also noted that Miyazaki is determined to make a strong comeback.

In 2013, Miyazaki declared his decision to no longer create full length movies, explaining the challenge of meeting his exceptionally high expectations. An American reviewer compared this announcement to a sudden obituary. However, four years later, Ghibli announced that its co-founder would be returning from retirement to create what would likely be his last film, taking into account his advanced age.

The outcome was The Boy and the Heron, serving as a testament to Miyazaki’s position as Japan’s ambassador of soft power. According to Frederik L Schodt, an author and translator involved in translating Miyazaki’s interviews and essays, there is no doubt that Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli have significantly contributed to promoting a favorable portrayal of Japan globally.

There may be new artists who come into the scene, but there is currently no one who can fill his role, and for unknown reasons, he has been unable to find a true replacement.

In a recent NHK documentary, Miyazaki appeared to have a different outlook on his career despite the passing of his Ghibli co-founder Takahata in 2018. Reflecting on the harsh reality of life, he stated, “Life is not always pleasant or morally right. It encompasses all aspects, even the disturbing ones. It is time for me to create a piece by delving into the depths of my inner self.”

The Boy and the Heron may prove to have been Miyazaki’s valedictory feature-length work, but he does not appear ready to step away from his suburban Tokyo studio just yet. Given his propensity for talking himself out of retirement, no one might be more relieved than the great animator himself.

Source: theguardian.com