You wouldn’t want to spend time with the kind of people you meet in the films of Australian director Justin Kurzel: the deranged loner of Nitram or the killers of his peerlessly disturbing debut Snowtown. Now, in The Order, Kurzel turns his attention to American neo-Nazis, and the people who hunt them – and, in the shape of Jude Law’s profoundly damaged FBI agent, the latter are not the cuddliest characters either. Premiering in competition at the Venice film festival, true-crime drama The Order is about the most dynamic thing seen on the Lido in the event’s first few days, and affirms Kurzel’s status as a formidable auteur, especially when it comes to the dark stuff.

Scripted by Zach Baylin and based on the book The Silent Brotherhood by Kevin Flynn and Gary Gerhardt, The Order recounts the early 80s hunt for a neo-Nazi militia group: a splinter faction from an extreme-right church, led by fanatics who want to stop praying and put the white supremacist agenda into murderous action. Law, who also produced, plays Terry Husk, the FBI man who arrives in the Pacific northwest to pursue the faction, while carrying scars from his career fighting the KKK and the mob; Tye Sheridan is a local cop who befriends him.

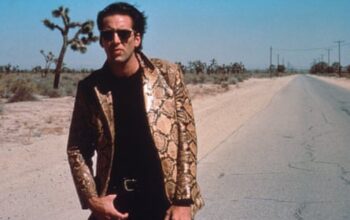

But the most out-and-out Kurzelian role here is taken by Nicholas Hoult, who was so disturbingly serpentine in the director’s True History of the Kelly Gang. Hoult plays the disarmingly named Bob Mathews, a blue-eyed angelic-faced country boy with a sweet smile, a heart of flint, and a ruthless agenda to establish an all-white promised land, to which end, he masterminds a set of bank robberies intended to finance a militia. The bible for his project is The Turner Diaries, an actual 1978 fiction-cum-tract which, closing titles tell us, has been used as a blueprint for American extreme-right actions right up to 2021’s attack on the Capitol – although it’s clear long before the film’s end just how germane The Order is as a commentary on today’s American fascism and its history.

While highly effective as docudrama, The Order is also briskly compelling as a straight-down-the-line detective thriller, especially in its action sequences. In the hands of editor Nick Fenton, the robbery sequences – especially a road assault on a Brink’s van – have a clean, propulsive urgency that recalls that of vintage thriller maestros like Michael Mann, William Friedkin and Sidney Lumet. And when the film broods, it really broods, as in a sequence by a river where Husk has a stag in his gunsights, while Mathews has his own sights on him.

But The Order has its fuzzier patches. The climactic face-off in the middle of a conflagration shows Kurzel opting for the apocalyptic at the cost of plausibility, while other sequences have a certain routineness: like the altogether generic sequence in which two lawmen carry on tersely discussing their case at the home of one of them, kids seen romping insouciantly in the background. There is also an overly theatrical scene in which Mathews stops a racist minister’s service by standing up and preaching his own gospel of murderous action. There are also some under-developed female characters: Jurnee Smollett as Husk’s long-term FBI associate, and Alison Oliver (Conversations With Friends) and Odessa Young as the two ill-used women in Mathews’ life. By contrast, there is a juicy featured role for comedian and cult podcaster Marc Maron as the real-life radio phone-in host whose defiant tilts at America’s racists and anti-semites establish the film’s theme.

Visually though, the film means business, with the desaturated, almost tawdry pallor of Adam Arkapaw’s photography evoking a weary early 80s America, in contrast with the richly tactile panoramas of the film’s northwestern forests, rivers and sweeps of rockface. As for Law – sporting a bristling moustache and some girth that evoke the weariness that Husk must fight in himself – he gives a sometimes warm, sometimes commandingly irascible performance that shows this actor moving confidently into middle-career authority. He and Hoult’s icy-eyed adversary combine to somewhat mythical resonance; a wrestle-with-the-demon duo that actually fits the political context to pointed effect.

Source: theguardian.com