It is easy to feel protective of Shirley Henderson on this gloomy winter afternoon. Is she warm enough? Does she want to put the heating on? “Aye, I’m OK,” she says from her home in Fife, a few strands of chestnut hair falling over her glasses as she huddles close to the laptop. “It’s a wee bit blowy out. But I’m at the age where you can get too warm, so I’m all right.” Her giggle is helium-high: the sort of sound you want to trap, like in one of those toy moo boxes, so that you can play it when you’re down in the dumps. Hearing Henderson laugh, or say “Sorry darlin’?” when she hasn’t quite heard your question makes you feel as if you’ve been cuddled.

Her allusion to the menopause, though, takes a moment to sink in. Though 58, she looks barely old enough to be online without parental controls. (No suspension of disbelief was required when she played a mother who dresses as her own adolescent daughter to sit an exam in May Contain Nuts.) Henderson came to prominence in the 1990s as one of the UK’s most probing, unpredictable character actors. After being spattered with excrement in Trainspotting, she won pivotal roles in two masterpieces: she was a soprano pining for her son in Mike Leigh’s Gilbert-and-Sullivan extravaganza Topsy-Turvy, and a feisty hairdresser smacking her lips at London life in the rhapsodic Wonderland. That was the first and best of her six collaborations with the director Michael Winterbottom, as well as the one which got her hooked on improvising.

Henderson’s new film, The Trouble With Jessica, brings her back to the capital, though this is a precisely drilled comedy, as macabre as its Hitchcockian title might suggest, with no room for ad-libs. She plays Sarah, who is about to sell her swanky London home, rescuing herself and her husband (Alan Tudyk) from financial disaster. Their closest friends (Rufus Sewell and Olivia Williams) drop in for a celebratory dinner, bringing with them the irritating Jessica (Indira Varma), who then has the temerity to kill herself in the garden, thus imperilling the sale. If only she had died elsewhere …

The corpse-shifting scheme turns out to be the making of Sarah. “She finds a kind of freedom in being the leader,” Henderson agrees. “She has this brutal, selfish idea. But what I was trying to do was get you to like her and feel a wee bit sorry for her. It’s OK to hate her for a moment. Yes, she’s bad but she is also sad and trapped. And she’s a smart lady to come up with all this!”

Henderson is the movie’s engine, her arms going like pistons as she scurries around placating police officers, nosy neighbours and the house’s prospective buyer. The sound of her heels clicking on the floor becomes a kind of metronome against which the action is paced and played. “I started to hear that clickiness myself,” she says. “I thought: ‘That’s the sound of her stress.’ She is this modern woman, trying to be everything, bring up her daughter, love her husband, take on this house they can’t afford, but bits are breaking off.”

When preparing for a role, Henderson comes to her little room to experiment with accent, movement, gesture: the pencil marks that will add up to the final portrait. “I start off thinking: ‘How will I ever be able to do this? What’s the first thing I’m going to do in the wee place where I practice?’ Then gradually, you realise it’s happening. You’re not thinking too much, you’re not forcing it. It’s there.” She refers to that “wee place” with such reverence that I’m picturing a glowing grotto or candle-lit shrine. “It’s just a tiny wee room,” she says chirpily. “That’s where I am now. If I’m up here, I feel I’m away from the world.” All I can see of it is the comfy coat hanging on the door behind her.

To think, it was here – or somewhere like it in a previous home – that Henderson first worked out how Hogwarts’ bathroom-dwelling ghost Moaning Myrtle would sound as she bleated her way through lines such as: “I was just sitting in the U-bend thinking about death.” It was here, too, that she practised warning Bridget Jones about disloyal boyfriends (“Even if he isn’t shagging her already, Bridge, he’s thinking about it”) and decided on the sad-but-sinister coochy-coo whisper of Frances, the lonely misfit manipulated by a psychopath in the second series of Happy Valley. And this must have been where she crafted her cameo as Agatha Christie in the madcap whodunit See How They Run, as well as her voice work as Quackety Duck Duck in the children’s series Lovely Little Farm and as the mewling Babu Frik in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker.

It was in this room, too, that Henderson would have worked out how to play the frantic Sarah in The Trouble With Jessica – if she’d been given more time, that is, rather than being offered the role three days before she was due on set. Possibly someone dropped out at short notice, she concedes. But this is also the way independent movies work, with the money often falling into place at the 11th hour. That’s how it was in 2017 with Never Steady, Never Still, where Henderson had just three weeks to adopt a Canadian accent and perfect the tremors of a woman suffering from Parkinson’s disease.

This shrewdness and versatility have made her a mascot of the international indie and arthouse scenes. She has worked with Kelly Reichardt (on the frontier western Meek’s Cutoff) and Todd Solondz (on the Happiness sequel Life During Wartime). She played Tilda Swinton’s PA in Bong Joon-ho’s Okja, and a tormented crone mutilating herself in pursuit of youth in Matteo Garrone’s Grimm-like Tale of Tales.

Film-making is always a circus. Three days to prepare for The Trouble With Jessica, though, sounds more like a farce. “It was manic,” she admits. “I had a ton of questions but there was no time.” Did she at least have her own dinner party memories to draw on? “You mean grownup dinner parties with couples?” she asks. “I don’t live that kind of life, do you? I’d rather go out to a restaurant because then you can get away quick if the chat gets too heavy.” What about hosting one? “No, no,” she says, covering her face with her hands. “I’d take everybody out before I did that.” Kill them, you mean? “Yeah, I’d get rid of them all. Haha! No, I’d take them out for supper, or for ice-cream. Let’s go out for pudding. Let’s go to the cinema.”

after newsletter promotion

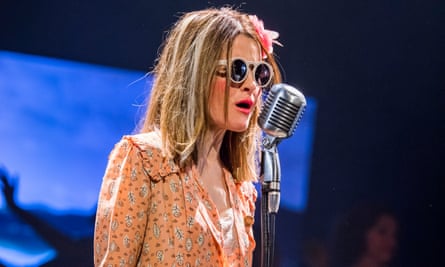

Or to the theatre. Henderson had one of the proudest moments of her career in 2018 when she won an Olivier award for playing a woman suffering from dementia in Conor McPherson’s stage musical Girl from the North Country, which was brimming with radical new arrangements of Bob Dylan numbers; Henderson’s rendition of Like a Rolling Stone, evolving from tentative to rollicking, was especially sublime. During her acceptance speech, she referred to her teenage diary, written when she arrived in London from Kincardine at 17 to study at Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where she was part of the same intake as her future Happy Valley co-star Sarah Lancashire. Henderson had given herself five years to sing on the London stage. It took a bit longer than that. Then again, she’s been busy.

How would she describe herself back then? “I was a wee girl with a wee Dannimac raincoat,” she says. “I knew nothing. I didn’t know I knew nothing. But that was fine. I wanted to learn. As a person, I was very quiet. Not chatty like I am today!”

She said in her speech that when Girl from the North Country arrived, it was everything she had been looking for. What is she looking for now in a script? “It’s a feeling,” she says. “A nervous feeling. But good nervous. Not a feeling like I know I can do it – I never feel that – but that I want to jump in and find out.” I think back to something she said earlier, when she was describing her character in The Trouble With Jessica. “My own natural energy, I suppose, is to always keep going. She has that too. She’s not done yet.” Neither is Henderson. Not by a long chalk.

Source: theguardian.com