Cultured, modest, intelligent: not words that immediately spring to mind when describing most Hollywood moviemakers. But for the writer-director Robert Benton, who has died aged 92 they are entirely apt.

Combined with a sparse output, those qualities kept him on the periphery of mainstream cinema and its publicity treadmill – despite Oscar-winning successes including Kramer vs. Kramer (1979) and Places in the Heart (1984), plus one of the most celebrated debuts in movie history when, at 35, he won his first Oscar nomination as co-writer of Bonnie and Clyde (1967). He was 40 when he made the Jeff Bridges western Bad Company – the first of only 11 feature film directorial credits.

Born in a small town not far from Dallas, Texas, to Dorothy (nee Spaulding) and Ellery Benton, who worked for a telephone company, Robert studied art at the state university before joining the army, where his talent found a modest outlet in the painting of dioramas. He subsequently studied at Columbia University before joining the art department of Esquire magazine, eventually becoming a contributing editor until he finally abandoned journalism in 1972.

During those years he formed two relationships crucial to his life and career. The first was with the artist Sallie Rendig, who illustrated his children’s book, Little Brother No More, in 1960. Four years later they were married. He also met David Newman, a slightly younger fellow editor on Esquire and they became regular collaborators, initially on books and then on an unsuccessful Broadway show, It’s a Bird … It’s a Plane … It’s Superman. When they wrote a film script it was with the French new wave director François Truffaut in mind, but luckily Bonnie and Clyde became a project for director Arthur Penn and actor-producer Warren Beatty.

This highly original take on 1930s rural lawlessness blended grotesque comedy with brutal actuality and became one of the most imitated of all movies. It enjoyed the rare distinction of being a cult success that moved on to become a critical and commercial hit.

The duo, who won two Writers Guild of America awards for best drama and best original screenplay, stayed in their day jobs while working on their next project, another brilliant, literary screenplay for a quirky western. There Was a Crooked Man (1970) starred Henry Fonda as a prison governor and Kirk Douglas as a devious convict. It was innovatory and witty, giving colourful roles to the fine supporting cast, just as its predecessor had done.

Having up-ended aspects of the western and gangster genres, the pair were called on for a script indebted to the screwball comedies of the 1930s in general and Bringing Up Baby in particular. Their screenplay, polished by Buck Henry, became What’s Up Doc? (1972) and won the WGA’s award for best comedy.

After contributing to Oh! Calcutta! that same year, they wrote what became Benton’s first – and most original – movie. Bad Company (1972) had a youthful cast headed by Jeff Bridges and Barry Brown as draft dodgers from the American civil war, travelling west and leading a small gang into lawlessness on their traumatic journey.

Once again the work took an almost perversely original view of its subject, blending dark comedy with a vivid portrait of a world where poverty is rife, thievery is commonplace and the myth of chivalry out west – perpetuated by movies – is completely demolished.

Benton gave up journalism, having enjoyed several productive and profitable years, although it was a further five years before his next movie, The Late Show (1977), written by him and produced by Robert Altman. Showing that nothing was sacred, Benton turned his attention to the private eye works of the 1930s and 40s with a sympathetic, even nostalgic, film that added a wryly comic twist to familiar characters. The hard-boiled detective had aged, there was a capricious modernity to the narrative and an elegance in the performances, the script and direction typical of his best work.

He received an Oscar nomination for the film and a lucrative commission to help on the screenplay for the 1978 Superman, directed by Richard Donner. After that blockbuster Benton made his first adaptation of a novel for the screen and the result remains his most famous work.

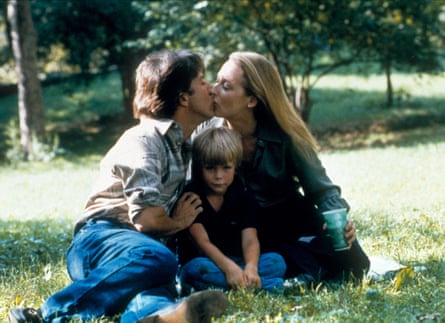

Although inherently conventional, Kramer vs. Kramer transcended melodrama to become, in the words of one commentator, “an upmarket new-fashioned tearjerker”. Its story, of a couple who divorce and start a battle over the custody of their son, struck a chord with audiences and with the less cynical critics. It also struck gold at the Oscars, with Meryl Streep and Dustin Hoffman collecting statuettes and Benton taking two, for best direction and best adapted screenplay.

As usual he had surrounded himself with the cream of the movie business. His rapport with actors meant that stars including Streep, Bridges, Hoffman, Bruce Willis and Paul Newman returned to work with him, as did the composer Howard Shore and designer Paul Sylbert, while the great cameraman Néstor Almendros shot five of his movies, before his untimely death in 1992 after filming with Benton on Billy Bathgate.

Despite the success of Kramer, Benton took time out before his next project and, interestingly, never looked to television or the theatre to mop up periods of inactivity. In 1982, another genre fell under his acquisitive gaze and, reunited with Streep, he wrote and directed the thriller Still of the Night. Some critics found Alfred Hitchcock’s influence oppressive and the story, of a psychiatrist who falls in love with his possibly murderous patient, conventional. The literary screenplay allowed the actors to adopt an overly serious tone for what was an old-fashioned suspense story brought into the 1980s.

Perhaps to shake off the claustrophobia of that movie, Benton headed for his native Texas and a sentimental story, which offered his lead actor, Sally Field, a heaven-sent opportunity to plunder Oscar-ville. It was a chance she successfully took through playing a tough, put-upon farmer battling against the Depression. Places in the Heart was filmed in and around Benton’s home town, drawing on locations and values of a time past and containing specific references to his ancestors. The highly personal work gained him another Oscar, for the screenplay, plus the Berlin festival Silver Bear for best direction.

Benton remained in Texas for Nadine (1987), a movie with roots in the screwball comedies and thrillers of Hollywood’s golden age that reunited him with Bridges. Considered a comparative misfire, it had admirers but proved difficult to assess, since various cuts gave the movie running times of between 78 and 88 minutes.

The gap between this mild-mannered movie and Billy Bathgate (1991) was several years, and his ambitious return to period-set gangsterdom failed commercially. It was the first time that he had worked as a director for hire, from a discursive screenplay by Tom Stoppard based on EL Doctorow’s novel. Hoffman took the lead, giving an intriguingly mannered performance as the vicious hoodlum Dutch Schulz. Visually it was memorable, but audiences were mystified by the sometimes witty and oblique tone, used as they were to more visceral depictions of 30s gangsterdom.

However, Benton was not a director given to compromise. His penultimate movie, Nobody’s Fool (1994), was a characteristically graceful work, starring Newman as a wilful 60-year-old living alone in a small town, forced to confront his alienation by the return of his son.

Benton introduced personal elements into his screenplay – not least for Newman, whose own estranged son had killed himself, and for Jessica Tandy as an elderly woman facing death. Critically the film was well received, but audiences showed scant regard for such a thoughtful character study.

Newman received an Oscar nomination for his cleverly nuanced performance, and four years later made yet another sortie from “retirement” to star in Twilight, the director’s second private eye movie. Heading a cast that included Gene Hackman, Susan Sarandon and James Garner, Newman was well cast as another ageing, alcoholic misfit – a detective living with a terminally ill actor and his wife, embroiled in a complicated blackmail scam.

Co-scripted with Richard Russo, whose novel was the basis of Nobody’s Fool, it owed much to 40s noir movies, but at 90 minutes seemed leisurely and was subject to postproduction editing. Praised for its atmosphere, laconic dialogue and ensemble acting, it proved overly sophisticated for modern-day cinemagoers.

The same could be said of his next film, The Human Stain (2003), which he directed, but did not write, from a novel by Philip Roth. Starring Anthony Hopkins and Nicole Kidman, it was an intriguing story of a distinguished academic who for years has hidden his racial origins. The film was crafted with Benton’s usual skill but was not a commercial success. Two years later he was reunited with his friend Russo on the screenplay of The Ice Harvest, a lively thriller with a witty and literate script directed by Harold Ramis. His final directorial credit was on a meditative film, Feast of Love (2007), concerning four different couples. It was not well received critically and took less than $6m worldwide.

However, it could not detract from the brilliant Bad Company, the witty homages to various film genres and the Oscar-winning successes of Kramer vs. Kramer and Places in the Heart by one of Hollywood’s most independent and original writer-directors.

Sallie died in 2023. Benton is survived by their son, John.

Source: theguardian.com