In 1985, the film “Favourites of the Moon” was released in France and introduced audiences to director Otar Iosseliani, who passed away at the age of 89. Prior to this release, little was known about Iosseliani in Western Europe. He had previously made three full-length films and a number of short films in the Soviet Union, where he faced censorship. This ultimately led to his decision to move to France in 1982. “Favourites of the Moon,” filmed in Paris and in French, served as an introduction for many to the unique world of Iosseliani.

His self-described “abstract comedies” are understated and incisive explorations of human absurdity, always faithful to his idiosyncratic vision, and discarding any kind of cohesive narrative. Iosseliani observed his characters through behaviour rather than dialogue. His use of sound and silence, and his complex movements of people, animals and objects made him the true heir to Jean Renoir, Jacques Tati and Luis Buñuel.

Born in the Georgian capital, Tbilisi (then called Tiflis), Iosseliani studied composing, conducting and piano at the Tbilisi Conservatory, and then took a degree in mathematics at Moscow University. However, he became drawn to the cinema, and graduated from the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK, now known as the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography) in the city, where he had attended classes given by the film director Alexander Dovzhenko.

When he was a student, he started his job at the Gruzia film studios in Tbilisi. He worked as an assistant director at first and later became an editor for documentaries.

In 1958, Iosseliani began his journey as a director. During this time, the Soviet Union experienced a period of increased freedom of expression known as the Nikita Khrushchev thaw. However, this period was short-lived as repression returned in the mid-1960s.

Unfortunately, Iosseliani’s 1961 film April, which ran for 46 minutes, was prohibited from being released due to its “excessive formalism”. However, it was able to be shown at the 2000 Cannes film festival. The poetic and slightly dreamlike tale of love depicts a pair of young lovers who project their affection onto their belongings while envisioning themselves in a new apartment.

With creative use of sound and little dialogue, the film already carried the original stamp of an auteur. “Everything that happens in my films has to do with people’s weakness for possession,” Iosseliani said. “And this leads to real values such as feelings disappearing.”

After a period of five years, during which he served as a sailor on a fishing vessel and worked at a metallurgical plant, Iosseliani completed his initial feature film, Falling Leaves (1966). This film displayed the distinct elements of his artistic style, as he aimed to “capture fleeting moments of life”. The plot takes place in a wine factory and follows the story of a sincere young man navigating through a world of Soviet corruption. In a display of his rebellion against societal norms, the protagonist does not sport a mustache, which is seen as a symbol of bourgeois propriety and masculinity in Georgia.

The film “Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird” (1970) playfully uses a common Georgian fairytale title to tell the story of a carefree musician in the Tbilisi orchestra.

Due to disapproval from Soviet officials, Pastorale (1975) was not shown in the western world until 1982 at the Berlin and London film festivals. This was also the year that director Iosseliani chose to move to Paris. The film follows a string quartet on their summer vacation in rural Georgia, where they encounter conflicts among narrow-minded peasants. Like many of Iosseliani’s works, Pastorale defies authority and offers a humorous and reflective portrayal of cultural disconnect.

Favourites of the Moon, his first French-language film, followed the separate paths of dozens of Parisian thieves, which constantly criss-cross as money, paintings and objets d’art change hands. For a short while the film seems to be a series of incoherent incidents concerning inexplicable characters (a pattern that was to be set for his subsequent work). But gradually the kaleidoscopic method yields a sharp satire on the greed and emptiness of bourgeois society.

The mostly silent film Chasing Butterflies (1992) follows a similar style to the works of Tati, utilizing long and graceful shots to showcase the absurdity and meticulousness of the physical world. Taking place in modern-day France, this allegory centers on two older women of high society who reside in a grand yet decaying castle. While they are content in their charmingly antiquated surroundings filled with old letters and art, the threat of commercialism, thievery, and greedy relatives loom over them, waiting for their inevitable demise.

The seventh chapter of Brigands (1996), which received a special jury prize at the Venice film festival, deviates somewhat from Tati’s farce and leans more towards Buñuel’s dark humor. The movie seamlessly transitions between the medieval era, Soviet Russia, and present-day Paris, featuring a tyrannical dictator, a Stalinist official, and a homeless individual as the main characters.

A portion of the movie was filmed in Georgia, signifying Iosseliani’s comeback to his birthplace after a span of 14 years. He asserted, “All my films are essentially Georgian films.” Despite the majority of his films being set in rural France, there is consistently a Georgian village hidden behind the exterior; and this village could easily be mistaken for any other village in the world.

The movie “Farewell, Home Sweet Home” from 1999 showcases a wealthy family from Paris who live double lives in secret, with absurd consequences. The film does not rely on jokes or intense scenes, but rather highlights the unpredictable nature of human behavior.

In his 2002 film “Monday Morning,” which received the Silver Bear award at the Berlin International Film Festival, Iosseliani shifted his attention to a single character: a middle-aged factory worker who rebels against his monotonous nine-to-five routine by taking a trip to Venice. This comedic work showcased the director’s talent for finding joy in the mundane aspects of everyday life.

In another subtle fable of self-liberation, Gardens in Autumn (2006), the unlikely hero is a sad-eyed, middle-aged cabinet minister. His life changes when he is discharged, and he leaves his vacuous lover and overbearing mother (Michel Piccoli in drag), to lead a carefree bohemian existence.

The focus of Chantrapas (2010) is a play on the French saying “Chantre Pas” (Cannot Sing), and it delves into the personal experiences of director Iosseliani more than his other works. The film follows a Georgian filmmaker as he struggles to maintain his creative independence in both the Soviet Union and France.

Nonetheless, Iosseliani, who had comical roles in his movies, refuted any personal purpose. “I never narrate what I have witnessed in my own life or in the lives of those around me. I merely create allegories and strive to make them relatable to real life, in order to ensure that people will trust in them.”

In 2015, Winter Song, the final movie he directed, depicted the residents of a Parisian apartment building who all resisted societal norms in their own unique ways.

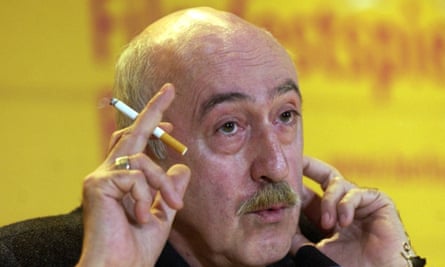

Otar Iosseliani, film director, born 2 February 1934; died 17 December 2023

Source: theguardian.com