This weekend, the BFI Southbank in London begins a season of films entitled Martin Scorsese Selects Hidden Gems of British Cinema. Among the treats that caught my eye are a terrific Terence Fisher double bill (1948’s To the Public Danger and 1952’s Stolen Face), Roy Ward Baker’s Dr Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971), John Hough’s The Legend of Hell House (1973) and a rare nitrate-print screening of Alberto Cavalcanti’s dark 1942 gem, Went the Day Well?

The fact that a director whose own extraordinary CV includes Taxi Driver (1973), Raging Bull (1980), The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Casino (1995), Gangs of New York (2002), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) and, just last year, Killers of the Flower Moon should curate such a season may seem remarkable. But Scorsese has always been a film fan as much as a film-maker, and the movies he has championed over the years are every bit as important to him as those he has made.

Anyone with a passing interest in film studies should check out the extremely watchable 1995 documentary A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies. Made with co-writer/director Michael Henry Wilson and produced by the BFI, this three-part documentary finds Scorsese examining the film director as storyteller, illusionist, smuggler and iconoclast. From Charlie Chaplin, DW Griffith and FW Murnau to Sam Peckinpah and Stanley Kubrick, it’s a very personal work that pays tribute to the film-makers Scorsese loves while emphasising the “need to look at old movies”, to “study the old masters, enrich your palette, expand your canvas”.

There’s an equally intoxicating mix of the historical and the personal in Scorsese’s 2024 documentary Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger, made with director David Hinton. Recalling his earliest encounters with films such The Red Shoes (a Technicolor marvel from cinematographer Jack Cardiff that Scorsese would rewatch endlessly on TV in black-and-white), Scorsese offers a riveting account of the pair’s collaborations, focusing on Powell and Pressburger classics such as I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and The Tales of Hoffmann (1951). But he also uses clips from his own movies to show what he learned from Powell and Pressburger.

In one fascinating sequence, Scorsese explains how director Michael Powell pulls away from a duel between two key characters in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, inspiring him to do the same in his depiction of boxer Jake LaMotta’s “big championship fight” in Raging Bull, in which the long walk to the ring is followed by cutting away from the bout itself. In both cases, it’s not the battle that matters, but what came before and after.

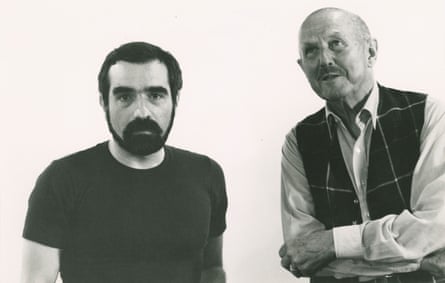

Scorsese was of course largely responsible for the resurgence of Powell’s reputation after the violent critical rejection of the British director’s 1960 chiller Peeping Tom, which Scorsese calls a “film maudit” (literally, a cursed film), about “the pathology, the obsession, the compulsion of cinema… the dangers of gazing”. In 1979, Scorsese helped get Peeping Tom into the New York film festival, and then rereleased, triggering its reassessment as a modern masterpiece. Powell, who later married Scorsese’s longtime editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, described the experience of the film’s rebirth as being like hearing “the cries of a newborn baby”.

“All this filming isn’t healthy,” runs a key line from Peeping Tom. “A friend of mine sent me that line on a note when we were making Raging Bull!” Scorsese told me when I interviewed him for the Observer in 2010. “And there is no doubt that [film-making] is aggressive, and it could be something that is not very healthy. It’s almost like a pathology of cinema where you want to possess the people on film. You want to live through them. You want to possess their spirits, their souls, in a way. And ultimately you can’t stop.” (Incidentally, that interview was being filmed on two cameras, and when our cameraman asked me for a synchronising hand clap, Scorsese – ever the director – instinctively did it himself, and then apologised because: “I didn’t do a very good clap there, sorry…”)

after newsletter promotion

As for his BFI season, that originated in a voicemail Scorsese sent to British film-maker Edgar Wright, who had casually asked “what some of your favourite British films were growing up”. Ever the cineaste, Scorsese came up with a reply that would put most professional film programmers to shame. “Watching the list was like completing a jigsaw puzzle,” Wright told me in 2021. “Lesser-known films from directors that I was aware of, darker offbeat films from famous studios and, most rewardingly, films that might have fallen through the cracks if directors like Martin Scorsese didn’t recommend them.”

He might be one of greatest film-makers of his generation, but Scorsese’s role as a cinematic historian – an enthusiastic flag-waver for cinema – may yet turn out to be his greatest legacy.

Martin Scorsese Selects Hidden Gems of British Cinema is at BFI Southbank, London, 1 September-8 October

What else I’m enjoying

Caligula: The Ultimate Cut

More than 40 years after it became a scandalous cause célèbre, Caligula returns to the big screen (it’s also available to stream) in an entirely new cut that finally makes sense of what was once just a lavish cinematic car crash. Disowned by original writer Gore Vidal and director Tinto Brass, Caligula (1979) was once called “the most expensive porn movie ever made” after producer Bob Guccione took over the edit and spliced in scenes of hardcore sex. Now writer, musician and art historian Thomas Negovan’s bold reassembly unearths a wealth of previously unseen footage, revealing one of Malcolm McDowell’s most mesmerising performances as the “anarchist” emperor intent on destroying Rome from the top. The result is a revelation!

Source: theguardian.com