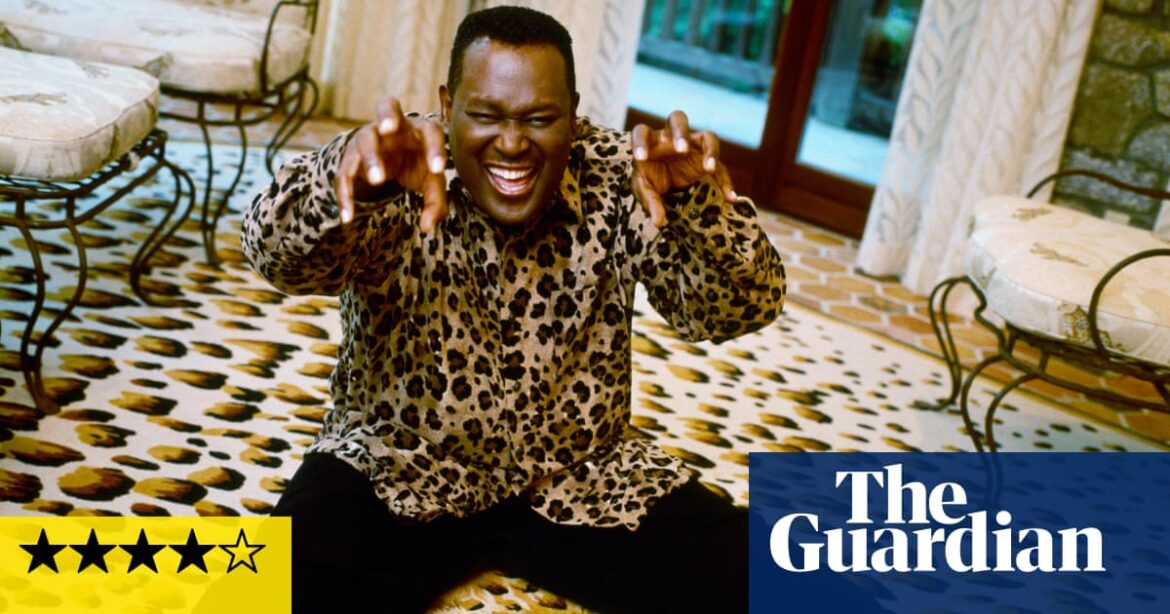

All of the mystery and certainty of love is carried in Luther Vandross’s radiant singing voice. On uptempo tracks he seems suffused with joy; on ballads he’s less sure, singing melodies that search high and low but still with hope in his heart. Those performances, and the complex life that informed them, are rightly given a feature-length canvas in this documentary by Dawn Porter, a US film-maker known for her studies of presidents, lawmakers and social movements, here making a rare foray into pop culture.

Porter rolls out an unbroken chronology of Vandross’s life, juxtaposing archive material with contemporary talking heads. That traditional approach is validated by both kinds of footage: old Vandross performances and interviews have been expertly filleted, while the talking heads are well-chosen, with A-listers such as Mariah Carey, Dionne Warwick and Jamie Foxx spritzing stardust between close friends, repeat collaborators and family members. The traditional framework also seems to acknowledge that Vandross was a cipher to many people, in need of someone to clearly tell a story he often obscured within himself.

If you only know him from hits such as the film’s title, surprises may be in store. He starts out in Listen My Brother, a 16-strong band singing socially conscious songs that get them hired to deliver wholesome educational numbers on Sesame Street. He also makes friends for life in bandmates Fonzi Thornton, Robin Clark and Carlos Alomar, who are all engaging and candid contributors here. Next he’s working with David Bowie – cue gorgeous studio footage of them working up Right together, from Bowie’s album Young Americans – as well as Bette Midler and Chic.

As Vandross’s own group, Luther, struggle, he makes money from ad jingles, and can be found singing about lager – “Tonight, let it be Löwenbräu”; “Bring your thirsty self right here, the rich sweet taste of Miller beer” – with the same ardour he later would bring to songs about endless love. And having had longer than most to hone his skills as a singer, songwriter and arranger, he is then head and shoulders above the rest of the R&B scene when Never Too Much finally kickstarts a multi-platinum solo career in 1981.

There’s more behind-the-scenes footage to cherish – working up Anyone Who Had a Heart round a piano; rehearsing a cappella with his backing singers – and Porter wisely lets certain performances play long, such as Vandross’s version of Dionne Warwick’s A House Is Not a Home. Performing live, his gift for extemporisation puts him in line with Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald as much as R&B or pop singers.

Warwick isn’t a particularly revealing talking head (nor Carey for that matter) but Foxx is excellent. “Back in the day, if you wanted to fall in love you let Luther do the work for you,” he says, explaining that he would phone a would-be lover and hold the receiver next to a loudspeaker playing a Vandross song.

Porter deftly explores how Vandross’s weight would go up and down in tandem with blatantly fatphobic scrutiny from the press, and how the genre divide between R&B and pop was essentially a form of racial segregation, holding Vandross back from universal success. And she tackles the central question in his life, his sexuality, with tact. His friend Patti Labelle is shown outing him on a talk show, and Labelle is upbraided here by Vandross’s songwriting partner Richard Marx. Time is given to Vandross’s own explanation – “I won’t even address it … what I owe you is my music, my talent, my best effort” – and his own favourite song in his catalogue, Any Love, which charts the pain of unrequited love. His story is tragic in a classic sense: nicknamed “the love doctor”, he cannot cure himself.

Even while honouring his wishes, there could have been a touch more on the particular bind he was in as the soundtrack to so many straight relationships in the generally homophobic 80s and 90s. And perhaps there could have been some other, deeper analysis. Oprah Winfrey and her multi-generational female studio audience are shown giddily melting under the heat-lamp of his voice, but there seems to be a certain unexplored quality to their admiration. Is this lust? Or perhaps Vandross provided something different that only he, with his mystifying sexuality, could provide; a simulation of the steadiness and friendship in love that is so rarely articulated in pop. Vandross’s specific power isn’t always fully articulated here – but his musical brilliance certainly is.

Source: theguardian.com