J

Jonathan Glazer was raised in Hadley Wood, near Barnet in the northern outskirts of London. His family was a part of a thriving Jewish community. He recalls having many interesting characters visit his house as a child, particularly those who had moved from the East End to the suburbs for a better lifestyle. These individuals were not necessarily intellectuals, but they were skilled entertainers such as vaudeville musicians and writers. Glazer greatly enjoyed and embraced the cultural diversity and richness of his upbringing.

According to Glazer, the topic of the Holocaust was never openly discussed in his household, but it was always a looming presence. When he informed his late father years ago about his plans to make a film about Rudolf Höss, the Nazi commander of Auschwitz, his father’s initial reaction was a mix of anger and dismay. His father questioned the purpose of bringing up such a painful past and urged him to let it remain buried. However, Glazer explained that he could not ignore the past and move on, as it was still relevant in the present.

It took Glazer almost 10 years to make The Zone of Interest (the characteristically neutral term used by the Nazis to describe the immediate area around the concentration camp), which will be released in UK cinemas in early February and which won the Grand Prix at this year’s Cannes film festival. During that time, there must have been moments when his father’s words echoed in his head, when the subject seemed so daunting that giving up and letting it rot may have seemed like the best option.

“I had a peculiar dynamic with the project from the very beginning,” he explains while we converse over coffee at a hotel in London. “I was committed to pursuing this path, yet I couldn’t help but feel prepared to backtrack at any given moment. I was almost hoping for an obstacle to arise so that I could give up and admit, ‘I’ve tried, but it’s not possible.’ I was almost willing it to occur.”

The final outcome is a bold movie, characterized by its formal experimentation and a detached viewpoint. Shot mostly with hidden cameras, it focuses on the daily life of the Höss family (consisting of Rudolf, his wife Hedwig, and their five children), whose home was situated just outside the perimeter of a concentration camp. The horrors within are only hinted at through glimpses of smoking chimneys, but the constant background noise of industrial machines and human voices is even more disturbing. This unsettling film delves into extreme cognitive dissonance and stayed with me for weeks after I first saw it. In fact, I attended another screening in an attempt to unravel its uneasy combination of clinical observation and sudden experimental elements – at one point, the screen turns blood red. On both occasions, it achieved Glazer’s goal of creating a narrative that requires the viewer to actively participate and ask questions.

The film was filmed at Auschwitz, with approval from the museum’s trustees. The crew utilized a vacant house near the camp and carefully reconstructed the villa where the Höss family resided for nearly four years, using historical images and survivor accounts. Unlike other movies about the Holocaust, it centers on the individuals responsible for the atrocities rather than the victims, with the camera remaining within the boundary of the commandant’s garden and not venturing into the camp.

Under the dispassionate direction of Glazer, we are shown how the couple’s home life was structured in a orderly manner, despite being in the literal shadow of Auschwitz’s smoking chimneys. While he oversees the systematic extermination, she socializes with friends, tends to her garden, and is assisted by local women with household tasks. In the evenings, he reads bedtime stories to his children and ensures all lights are turned off and doors are locked before going to bed. Together, they celebrate birthdays, have picnics by the pool, and reflect on their past and make plans for their future from separate beds. Glazer reflects on the difficulty of acknowledging the couple as human beings, as it highlights the horror of the film’s journey. However, he believes that by doing so, we may see ourselves in them. The film is not just about the past, but also about the present and our potential similarities to the perpetrators rather than the victims.

According to the speaker, the focus is not solely on analyzing Nazi ideology, but rather delving into a deeper aspect of human nature. While some understanding of the ideology is necessary for writing about it, the goal was to create a movie that explored the underlying primal instincts that drive violence, a capacity that exists within all of us.

S

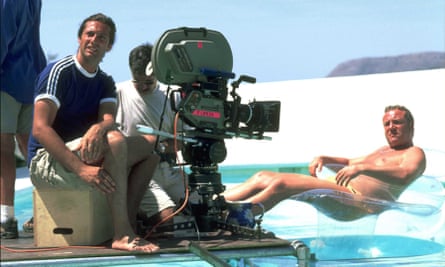

Since his first movie, the edgy and stylish British crime thriller Sexy Beast, was released in 2000, Glazer has become known as the most ambitious and focused British director of his generation. He has listed Stanley Kubrick as an influence and has expressed that he identifies more with Russian and Italian cinema than British cinema. Glazer’s background in theatre design led him to filmmaking through directing successful advertising campaigns in the 1990s, such as the iconic Guinness surfer commercial featuring white horses emerging from rolling waves. He also directed impressive music videos for bands like Radiohead and Massive Attack.

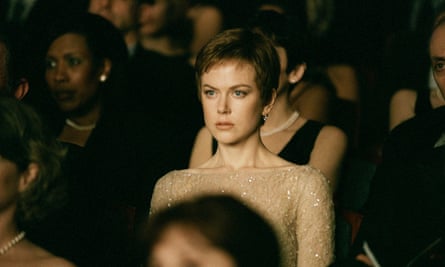

Since Sexy Beast was released 23 years ago, the director has only created three films, including his latest one. With each new film, the subject matter becomes more ambitious, the structure more complex, and the journey from conception to completion more prolonged. His second movie, Birth (2004), which featured Nicole Kidman as a grieving wife under the influence of a young boy claiming to be her deceased husband reincarnated, took four years to make. It then took an additional nine years for his next film, Under the Skin (2013), a sci-fi noir based on a Michel Faber novel and starring Scarlett Johansson as a seductive alien who preys on vulnerable men in Scotland and submerges them in a mysterious world.

For the movie, Glazer recruited inexperienced actors for the supporting roles and utilized hidden cameras for several scenes where Johansson’s character approaches young men on the street. The unsettling atmosphere was intensified by the disorienting sound design by Johnnie Burn and the persistently foreboding score by experimental musician Mica Levi, both of whom have collaborated closely with Glazer on The Zone of Interest. When asked about the level of dedication required to work on a Jonathan Glazer film, Burn stated, “Under the Skin almost destroyed me. I was extremely ill from working long shifts and not getting enough sleep. Once you become a part of Jonathan’s team, you start to view the film in the same way he does. It becomes all-consuming.”

I

Glazer, a resident of Camden, north London, shares similarities with Kubrick in his dedication to his craft. When asked if he is similarly fixated on his filmmaking, he confirms without hesitation. The inspiration for his film, The Zone of Interest, came from reading Martin Amis’s novel of the same name in 2014. After obtaining the rights with producer Jim Wilson, they spent several years thoroughly preparing for production. Glazer explains that their research led them beyond the book and into Amis’s primary sources, particularly the Auschwitz archives. As they uncovered more information about Rudolf and Hedwig Höss, Glazer was struck by their working-class background and aspiration to become a bourgeois family, which is a relatable desire in today’s society. He found their familiarity to be both grotesque and compelling.

Acted by Christian Friedel and Sandra Hüller, the pair represents the belief of Jewish writer Primo Levi that it is everyday individuals, not monsters, who have the ability to commit horrific acts. In his words, “Monsters exist, but they are too scarce to be a real threat. It is the average men, the officials who are willing to believe and act without questioning, that pose a greater danger.”

The normality of the couple is shown through a sequence of scenes that were partly planned and partly improvised, captured by small, stationary cameras hidden around the house and yard. The actors were not informed of the exact locations of the cameras. Glazer and his team stayed off-set the entire time, observing the footage on a group of screens in a different building. The outcome is a film that resembles candid surveillance, which Glazer humorously compares to “Big Brother in a Nazi residence.”

According to him, his goal was to create a film that appeared to have no specific author. As the director and creator of the film, I inquire if it is feasible to achieve a detached perspective. He responds, “No, it’s not possible to completely detach, even though I wish it were. But the aspiration is present. The reason I was not present on set was because I wanted to observe the characters in an anthropological manner. I was not interested in their personal struggles, but rather wanted to observe them in the most unobstructed way possible, in order to understand their behavior and actions, and ultimately their identities.”

Glazer recognizes that the choice for the main roles was significant for the two performers, considering the content and the fact that it was filmed at Auschwitz. They were tasked with portraying characters who could have been their own grandparents. Friedel, known for his role as a teacher in The White Ribbon, a thought-provoking film about the origins of Nazi beliefs, portrays Rudolf Höss as a mysterious figure prone to contemplative pauses and intense gazes into the distance, leaving the audience curious about his thoughts.

Hüller is receiving high praise for her performance in Justine Triet’s intricate legal drama, Anatomy of a Fall. She fully embodies the character of Hedwig, to the point where it was disorienting to see her appear on stage after a recent screening at a New York film festival, dressed elegantly in a geometric designer suit. During the event, she openly discussed her initial disgust upon learning about the film’s subject matter. “I have to admit, it made me physically ill. It was a shock to me. I never expected to be a part of this type of story or to play a character like Hedwig Höss.”

It took Hüller, who comes from a leftist German theatre background, a full year to agree to be a part of the film. However, she is the most captivating presence in it: a ruthlessly self-absorbed individual who lacks conscience and empathy, and is unaware of her actions. She stands in front of her bedroom mirror in a fur coat and lipstick stolen from a Jewish prisoner, bragging to her mother: “Rudi calls me the Queen of Auschwitz.” When she learns that Rudi will be transferred to another death camp, she becomes frantic with rage at the thought of leaving, shouting: “You can’t do this to me! We’re living the life we’ve always dreamed of.”

Hedwig is always occupied, whether giving orders to her followers or worrying about her husband’s standing in the ever-changing alliances of the Reich’s inner circle. When creating the character, Glazer was inspired by philosopher Hannah Arendt’s description of the Nazis as lacking critical thinking. He explains, “There was a belief that nothing should pause and no one should pause. Everyone had to be constantly engaged in activity because if you stop, you start to think. And if you think, you reflect. But with Hedwig, there is no reflection or consideration for anything or anyone besides herself. She is persistently busy to avoid thinking.”

The author hints at the horrors beyond the protagonist’s garden by including various subtle but significant visual elements: a Polish worker washing Rudolf Höss’s leather boots, stained with red water from a tap; a gardener spreading ashes from the camp onto the soil of Hedwig Höss’s carefully maintained flower beds; their daughter sleepwalking; their eldest son bullying his younger brother by locking him in the greenhouse and imitating the sound of gas hissing; and even the family dog appearing constantly on edge, running through the garden and sniffing at the ground beneath the wall.

During his initial visit to Auschwitz, Glazer was surprised to discover that the Höss family’s house was still occupied by a Polish family who had been living there since the war ended. He recalls seeing the remains of the garden and how close it was to the camp’s wall, which was a chilling experience. Afterward, he entered the camp and viewed the wall from the opposite side, attempting to imagine what the prisoners must have heard. Glazer reflects on the stark contrast between the happiness and laughter of the Höss children playing in their pool, and the horrors that the prisoners would have experienced. This realization became a central theme in his film, highlighting the proximity of joy and terror and how one person’s paradise can be another’s hell.

The film portrays a sense of absence, while Burn’s use of sound effectively conveys the suffering of the victims. The constant noise of machinery, the commanding voices of SS guards, and the agonizing cries and screams of prisoners being led to their deaths in the gas chambers all contribute to this haunting atmosphere. According to Glazer, there are essentially two films within this one – the visual and the auditory – with the latter being just as crucial, if not more so. The imagery of the concentration camps is already well-known through real archival footage, making it unnecessary to recreate it. However, by incorporating sound, Glazer hoped to evoke a vivid mental image for the audience.

Burn dedicated a year to conducting research and collecting a large collection of sounds. The goal was to create a record of all the sounds that could be heard at the camp, which served as both a site of intense industrial activity and immense human suffering. This task proved to be extremely challenging. Burn recalls telling his wife after only a few weeks that the project was taking a toll on him. Despite never directly showing any horrors, he describes it as the most violent film he has ever worked on.

The beginning of The Zone of Interest is disorienting, starting with two minutes of darkness while Levi’s electronic overture plays in the background. The music gradually retreats as the screen comes into focus, revealing a shot of the Höss family enjoying a picnic by a Polish lake in the bright sunshine, accompanied by the sound of wild songbirds. Levi explains that the music and dark screen serve as a preparation for what is to come, immersing the audience in a different reality. He adds that the music gradually descends in pitch, guiding the audience deeper into the story. Throughout the film, the music serves to transport the audience to a place beyond what is seen on screen, almost like a place that cannot be fully comprehended.

The movie’s premiere was preceded by tragedy. The showing I attended in New York occurred shortly after the devastating Hamas attack on Israel in which many lives were lost and hostages were taken. As the film began, there was a sense of unease and apprehension in the air, with the festival curator nervously leading a brief Q&A session afterwards. I spoke with Glazer a week later, during the early stages of the Israeli offensive on Gaza, which has now claimed many more lives. It is certainly a critical moment to release the film. Glazer agrees, acknowledging that the film’s relevance will persist until humanity can break free from its cycle of violence. Unfortunately, he believes this change will not happen in our lifetimes. He also mentions being mindful of current events and their impact on the film’s complexity.

I inquire with Glazer about his readiness to receive criticism regarding the ethical portrayal of the Holocaust. He confirms his preparedness but also expresses curiosity about the arguments that may arise. In his opinion, tackling the subject is crucial but the main concern should be how it is done. He believes that the story must continue to be shared and adapted for each new generation, especially as the number of survivors decreases and the event becomes a part of history rather than living memory.

At night, the only glimmers of hope in the Zone of Interest are captured on a thermal imaging camera, similar to the one used by photographer Richard Mosse for his refugee film, Incoming. In a construction site under a railway leading to the camp, a young woman, appearing ghostly on camera, secretly leaves apples in the ground for the hungry prisoners on work duty to discover the next day. During this act, she uncovers a tin buried in the earth containing sheet music.

The encounter occurred when Glazer met Alexandria, a 90-year-old woman who had been part of the Polish resistance at the age of 12. She shared her story of cycling to a camp to leave apples and discovering a piece of written music, composed by Thomas Wolf, an Auschwitz prisoner who survived the war. Glazer explains that the house used for filming was Alexandria’s residence, and the bike and dress used in the scene belonged to her. Unfortunately, she passed away a few weeks after their conversation.

He takes a long pause. “The small but powerful act of resistance, of leaving food behind, is essential because it is the one glimmer of hope. At that point, I honestly believed I couldn’t continue making the film. I kept calling my producer, Jim, and telling him: ‘I’m quitting. I can’t do this. It’s too depressing.’ It felt impossible to only show the darkness, so I searched for a source of light and found it in her. She is the driving force for good.”

I ask Glazer what made him persevere with the project each time he felt the urge to give up and walk away. “I don’t know for sure. My heritage, maybe. Inter-generational trauma. Fear. Anger. All of that stuff. Most Jewish families have a history with the event because it was so enormous. Just looking through the archives of Auschwitz and going though my family names, I discovered there are a lot of them. So, I think it’s just in you.”

He hesitates once more. “I created this film to remind us of our intimate connection to this horrific event that we often view as something from the past. But for me, it is always present and at this moment, I can sense and fear that these events are resurfacing with the spread of right-wing populism globally. The path that countless individuals once followed is just a few steps away, always within reach.”

-

The release date for The Zone of Interest in the US is set for December 15th, and in the UK it will be available on February 2nd, 2024.

Source: theguardian.com