N

According to common belief, not all movie protagonists wear capes. However, there are a select few who don blue overalls and rubber gloves. “Perfect Days,” the stunning drama directed by Wim Wenders, centers around one such individual: a solitary figure navigating through modern Japan. Hirayama, a middle-aged man, works for Tokyo Toilet and travels in a small van to different public restrooms. Similar to iconic characters Travis Bickle and Dirty Harry, Hirayama is determined to improve the state of the city. Yet, his methods differ as he carries cleaning supplies such as brushes, squeegees, and detergent.

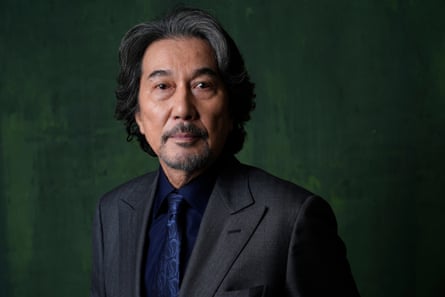

Kōji Yakusho, a 68-year-old veteran of Japanese cinema with over 100 screen credits, portrays Hirayama in this film. He has had notable roles such as the enigmatic diner in the 1980s hit Tampopo, the grief-stricken father in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Babel, and a remorseful killer in the award-winning drama The Eel. However, he has never been a part of such an intriguing project and has never seen a film generate such excitement and acclaim. He received the best actor award at last year’s Cannes film festival and now, Perfect Days has a chance at winning the best international film Oscar. In his calm and reflective manner, Yakusho is still trying to make sense of it all.

“It was an unusual and unexpected journey,” he remarks, especially considering that Perfect Days was initially intended to be a short documentary for the Tokyo Toilet art project. This project featured 17 architect-designed public bathrooms in Shibuya, Tokyo. What was supposed to be a small project turned into a large production. Yakusho arrived late and almost had a bathroom emergency. “I had never been to public toilets before,” he explains, before clarifying, “I had never been to these particular public toilets before. I wasn’t aware of the Tokyo Toilet art project, so it was all very intriguing and meaningful to me.”

Display the image in full screen mode.

Hirayama’s daily routine is highly structured and follows a strict order, resembling that of a monk. He wakes up early and tidies his bed. He grooms his mustache and tends to his houseplants. Then, he begins his usual rounds, playing his favorite cassettes (featuring artists like Nina Simone and Van Morrison) on the vintage tape deck in his van, a nostalgic relic from a simpler time. Hirayama’s job is mundane and he seems to have little connection with friends or relatives. However, he feels content with his life choices.

The film Perfect Days was shot in a documentary-style over a 16-day period, with director Wenders using a translator to communicate. Actor Yakusho fondly recalls the experience, sharing that Wenders wanted to capture everything, even rehearsals. As a result, Yakusho found himself living the life of his character, Hirayama, both at home and at work. The filming process went smoothly and at the end, the managers at Tokyo Toilet jokingly offered Yakusho a permanent job as a janitor. However, he can’t be certain if it was truly a joke or not.

Hirayama, despite being a solitary individual, is not exempt from dealing with a careless colleague and a runaway family member. In the evenings, he often dines in a bustling covered market. Interestingly, his true co-stars may actually be the public restrooms themselves. These facilities vary from a harsh, futuristic pod to a vibrant glasshouse that turns opaque when occupied. From afar, these structures could be mistaken for pristine works of art. However, upon entering, one will find them to be impeccably clean. Wenders’ film portrays Tokyo as a harmonious and hygienic city. If the same story were to take place in London, it would likely be more fitting for a horror film.

Yakusho agrees and sadly reflects on his past encounters with Western toilets. He believes that the cultural approach to cleanliness may differ in Japan, as they are taught from a young age to maintain a high standard of hygiene when using the restroom. They are also told that following this practice will lead to positive outcomes.

Ignore the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

Display the image in full screen mode.

He continues to contemplate the topic. “Perhaps it is ingrained in our society,” he suggests. “But there is also the belief that God exists within all things. This means that even a toilet is considered to be inhabited by God. It’s a positive mindset to have. When using the toilet, you are in the presence of God. And if you hold this belief, you will show respect for his presence and be considerate of the next person who will use the toilet.”

The actor’s personal background leans more towards white-collar jobs rather than blue-collar ones. His given name is Hashimoto, but he goes by Yakusho as a stage name. The name roughly translates to “government office” and relates to his previous job as a junior civil servant, right before he became interested in acting. “I’m from Nagasaki,” he shares. “And in those rural and small town areas, everyone dreams of moving to the big city, Tokyo. That was my initial motivation. I worked as a civil servant for four years, and I probably would have returned home eventually if I hadn’t discovered my passion for acting and decided to pursue it, which I am still doing now.”

Yakusho’s first major success with global audiences came from his role in the romantic comedy Shall We Dance in 1996. He portrayed Shohei Sugiyama, a disheartened accountant in Tokyo who finds a new passion for ballroom dancing. While some may assume this role resonated with him personally – a stagnant office worker invigorated by the world of performance – Yakusho maintains that any similarities to his own life were only surface level.

“I did not wear a suit,” he explains. “I didn’t have to go to the office every day, but I do recall the crowded commuter trains. As a young civil servant, I was not yet cynical or uninterested. My life during that period revolved around drinking, having fun, and exploring Tokyo.”

If the book Perfect Days includes any overt and loud expressions of a message, it is that a life spent in service has purpose and even low-paying jobs hold worth. As Hirayama moves about the public parks, Wenders pauses to savor the city’s ambiance, reveling in the buzzing of morning traffic and the way sunlight filters through the trees. The janitor, though part of the everyday routine, is hinted to possibly be something more. He could be seen as a secular saint among us, or a hidden tailor keeping society’s fabric intact.

According to Yakusho, he is a content individual, but I question the validity of this statement. Although Perfect Days lacks background information, it’s evident that Hirayama is not completely at ease with himself. He is trying to escape his past and is frequently haunted by past experiences. Many critics have interpreted this as a touching film about happiness. However, it can also be seen as a cheerful film about emotions such as sadness, isolation, rejection, and hopelessness.

Yakusho agrees, “Absolutely. Any interpretation is valid. However, I believe he is satisfied with the life he leads. Although he may not possess many possessions, he embraces each moment and finds contentment. Objectively, his life is one of happiness.”

Can Yakusho relate to the life he envies? Overall, yes. In Japan, there is a saying that being content with your circumstances and appreciating every moment leads to fulfillment. If one can achieve that, they will have a fulfilling and abundant life. So, yes, I would like to live like Hirayama, but I understand it is not simple. Cleaning toilets, now that would be a test.” Yakusho grins.

Source: theguardian.com