Miranda July has rented a little house in LA for 20 years. Every morning she’d drive over from the home she shared with her husband and young child, work on her films and art and writing and drive home again, until one day she noticed that another little house, the little rundown house that backed on to hers, was empty, and she had a thought. Something was shifting in her, it had been shifting for some time.

The shift started when, after signing on to publish her second novel, July realised the most valuable time for her to write was early in the morning. One day she said to her husband, film director Mike Mills, “I’m going to ask something,” and she took a breath. “What if I spent one night a week in my studio?” She is talking to me from that studio, the first little house, in a hoodie and spectacles and a pink plaid jacket, leaning in wide-eyed as she remembers the fear. This is not what parents do, she’d thought, shaking a little, this is not how life works. But… what if?

When she’d tell friends about her new Wednesday nights, alone, “Everyone would be kind of shocked, like wait a sec, how did you get that? I didn’t know that was a thing we could get.” She’d reply, “‘I mean, I just thought of it and it seems fine.’ But it was one of those things where you pull out one thread and then it’s like… why is everything the way it is?” Soon she had moved full-time into the second little house, splitting from Mills, co-parenting and creating a kind of compound – a new little life built on to the back of the old one. She has rebuilt the place piece by piece, finding old rugs and sofas through tips from fans, employing a young artist to build a kitchen in butter yellow gloss. “The reason I had this studio was not just for practical reasons – I needed this psychic space, this aloneness to be free in.” Here, instead of being a mother, or a wife, she was just a person.

July grew up in California then moved to Portland, Oregon. She took the name July at 15, after a character in one of her best friend’s stories, changing it legally at 20 – she was involved in the post-punk Riot Grrrl scene by then, making music and working as a stripper in a peep show to fund her art practice. After the release of her award- winning film Me and You and Everyone We Know in 2005, some critics responded (as they would about much of her work that makes the mundane seem remarkable, dealing with loneliness, love, sex, violence and death) by dismissing it with descriptions like “twee”, while her male peers were credited for their surreal genius.

Perhaps this goes some way to explaining why, despite having work in major collections across the world, this year sees her first ever solo gallery show, at the Fondazione Prada in Milan, charting 30 years of her work. In conversation about the show, Cindy Sherman marvelled at how July “thrives in scary situations, in risk-taking”.

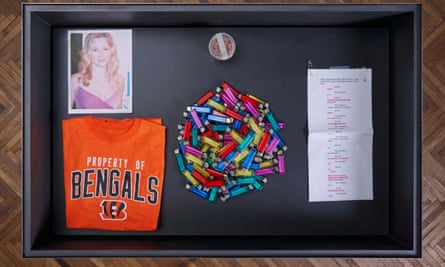

I visited on a warm afternoon a few weeks after July had left – she had stayed for too long, she said, talking to visitors, listening to their stories, “Being super nerdy.” There is a short blonde wig on the wall, which July wore in her 20s working at the peep show, and a piece created with her one-time Uber driver, and everywhere, evidence of her urgent, joyful, sometimes impossible, need to connect with other people. I lost myself for a little while, watching a film of her 2015 piece New Society, in which, inviting an audience to join her in transforming the theatre into an intentional community, she gestured to the possibility of another, better world.

Soon after beginning those Wednesday sleepovers, July started to realise something about herself. “I’ve never followed any rules as to my career…” she starts – a career which has, in her 50 years, produced three feature films (two of which she also starred in), a book of short stories, art (including an exhibition at the Venice Biennale) and now two novels. Vanity Fair describes her career as “multifaceted”, and in 2012 the satirical magazine The Onion ran a piece titled “Miranda July Called Before Congress To Explain Exactly What Her Whole Thing Is” – “But I didn’t realise that rulelessness could extend to my whole life.”

Those Wednesday nights felt full and rich, like a whole year at a time, and she started to see “that just as the structures around a career didn’t exactly fit me, the same is true with my home and romantic life”. It was around this time that she started researching her novel by interviewing scores of gynaecologists, naturopaths and older friends about menopause, eventually focusing on what this stage of life means for desire. The process sounds equal parts liberating and derailing. “I’m OK now,” she promises, “but only because I changed my life while writing – the book was my companion and confidant, but there were many points early on where I was like, this is an impossible book.”

Why? “There was the thought: should I just grow up? Get over myself, get it together, whether it’s a feeling about the body or about marriage, or getting older or sexuality, desire, all these things?” All these little things. But through those conversations she came to believe that menopause “might not just be a problem, but a really important time. And I would often think, if men had this huge change, it would be considered monumental! There would be rituals. There’d be holidays. There’d be rights and religions, and so, once I worked through the need to simply educate,” which, it so happens, she does – this is a novel that contains charts and statistics alongside “giddy, bold, mind-blowing” (according to George Saunders) prose, “I came to think it was the mythology that’s missing. The many varied and contradictory accounts that ultimately create the picture of an important time.” When we get our periods we’re told we’re becoming a woman. What do we become when we hit menopause? “No,” she lifts one finger, clarification, “when we get our periods we become a woman for men, because that’s when we can procreate. Now, we become a woman for ourselves.”

Talking to these older women, she started to consider time in a new way. As a young person she’d thought ahead to the family she might have, the fantasy, maybe, of being a star. Now at 50, “When I look ahead the same number of years, then it’s death at the end. You start setting your goals.” To my polite open mouth she says, gently, “I’m giving you the sense of the headspace that I was in when I was writing, which was, ‘Who do I want to be as a dying person?’” Here is, maybe, the hidden, spiritual element of the book. “So much of what you thought was you was maybe really other people. That starts to become more clear. And the weird part is,” she chuckles earnestly, “there can be discomfort, but I think there’s a kind of psychedelic joy to it, too.” And this is what the novel, All Fours, revealed itself to be about.

So, OK. This book. I read a proof copy early, and then I put it down and shakily messaged a series of friends, and then I read it all over again. It’s the story of a semi-famous artist navigating the second half of her life. She sets off on a road-trip to New York alone, but finds herself instead secretly checking into a motel half an hour from the home she shares with her husband and kid. Once there, she transforms first the room, then slowly herself, falling awkwardly in love with a stranger, but also with this new raw freedom. When she gets home she realises she needs to reinvent everything – her sexual, romantic and domestic life, and, crucially, that time is running out. It’s very funny, quite dirty, and deeply profound, with a fragile magic that comes from entering an uncensored inner world. There is the added thrill as well, of July suggesting that midlife, and menopause in particular, might be kind of… hot.

Slowly my friends read the book, too, and independently, three different women called to say, I’m worried, oh no, I think this might change my life.

In the novel the heroine finds freedom and transformation through two things – the first is dance. And when I ask about dancing, the first thing July describes is what it means to do so in a 50-year-old body. “It’s funny, I was just at my exhibition looking at all these videos of me, of my young body, 24, wearing a bathing suit, and I was thinking, what am I doing there?” She works it out. “I had just been a stripper for two years, so I was very familiar with this body. It’s like if you were born with some weird sculpture you had to carry around with you everywhere. You have all this stuff to say, but you can’t get away from the sculpture. You think, ‘OK then I’ll put it here on the stage!’”

Now she dances daily, often on Instagram, a place that has become a new sort of stage for July. “For someone who walks around feeling like a brain with two periscope eyes, being able to get up from working and suddenly feel things in ways that actually bypass my intellect,” is important. It’s about trying to let go, to get free. As she gets older, “It feels more interesting, because I’ve seen less of that, right?” Fewer older women, moving on camera. “A woman feeling out their body and their day.”

In the book, dance is art, in an abstracted sense. “I’ve given my life to making things, a lot of them, really, that no one will ever see, but still I’m so moved. So I wanted to be able to acknowledge, that… [she shakes her head, the words are too simple to describe the feeling] that it has all been… utterly worthwhile.” The other side of it is that July loves to perform, she always has. The feeling, “Is this kind of free ecstatic freefall, a little like: I can’t be hurt, like I’m safe while performing and so I can just become more vulnerable. Like, I can’t die up here,” she laughs, shocked maybe. The flip side of this is, in a lower voice, “that the rest of life can be a bit excruciating.”

after newsletter promotion

The second route to freedom, we find in All Fours, is sex. This is sex as duty, sex in fantasy, sex as an expression of desire, fury, boredom, transformation, joy, connection, sex unsightly and alone, and unexpected, and as a way of splitting open reality. What the character focuses on when learning about menopause is that women’s libido can drop off a cliff. Sex here “is a placeholder” for all the living left to do. “I just wanted to get it down accurately. I kept notes. I felt like it was really important to get across that women are not consistent sexually. Why should they be?” And, she smiles, “I’ll tell you, I wrote a lot of stuff that was fun to write, it even turned me on, but – it wasn’t actually true.”

These were sex scenes we might recognise from other films or books, erotic, maybe, raw, possibly, but not real. “And it would take me a while to realise it, but then I’d have to delete everything. Because – that’s not what she would look like masturbating. It wouldn’t look that sexy. I remember writing the sort of ugly rigor mortis, and feeling like, OK, I’d want to read that.”

In the earlier parts of July’s career, the goal was simple: “Make a fucking movie.” Now, she realises, her various works, “have become more rituals for myself. Because I desperately need something, things are not OK. And given that it’s my life, it’s on me to figure it out. To transform, take risks and make mistakes and do the whole process of reshaping.” As well as reshaping her work, leaving her marriage, taking a girlfriend, knocking down walls, what does this involve? “Many, many conversations with dear friends.” These conversations sometimes feel, she says, “very criminal”, whether about desire or what it would look like to live their work lives according to their menstrual cycles, and “giving each other permission to be a mess and be internal and not present in any incredible way”. About being a mother, too – in the acknowledgments she thanks her child, who is trans, for “emboldening” her. The reshaping process also, crucially, involved this book. “Writing it was like a bet I was placing, that there would be this conversation on the other end, and that I wasn’t as insanely alone as I felt.”

It wasn’t until halfway through my second reading that I realised our heroine has no name. July did try several times to name her, if only to make clear it wasn’t memoir. She decided not to fight it. To be generous with herself and give the character the right contours so readers could project July on to her, if they wanted. “I know people won’t be able to get the ratio right of fiction to me, but I think it will bring joy to the book; I think it’ll bring intimacy and pleasure.” Some people will read it as her life, “but it seems worth the risk for the energy it brings”. In the first months of writing about menopause, she started to worry that it would expose her, suddenly, as old. She dealt with this by embracing the fear, “By actually pointing right at everything that I would be gracefully trying to conceal, or dance past,” in order to get this conversation with other women, about age, desire, ambition, motherhood. A conversation that would sustain her into old age, “and stay interesting”. She pauses. “I really need that to be true.”

Both her novels also offer new, sometimes painful ways into a conversation about birth trauma, illuminating that dark, bloodied line between life and death. When writing a scene about PTSD that overlapped with her own experience of childbirth, July found herself crying. “I’ve felt differently since writing it, almost like my body thinks that happened. I guess that’s what ritual is for, and writing. To tell yourself something.” And then, thankfully, us. She wrote in very small letters on Instagram, “The truth is, no book can hold all of life. But we have to try.”

July’s work tends to scratch at the tension between vulnerability and self-preservation. And yet recently she realised, “I wasn’t that good at being vulnerable.” She was good at one part of it perhaps, but until she started to shrug them off, she was blind to all the other kinds of “armours” she wore. “Vulnerability is like a starting place, for anything that might be new. And it’s such a relief when you realise that there’s something you can let go of. But – vulnerability isn’t, in fact, that vulnerable. It’s… power.”

In choosing the title All Fours, she asks us to reconsider a position associated with submission and powerlessness. On all fours, “That’s actually when you’re most stable, in that undefended place.” Later that night I watch on Instagram as she videos the young artist putting the final screw into her new yellow kitchen, and she posts a note – when she’d first started renting this second little house she’d wake in the night, worrying about the decisions she’d made. But now it offered proof that there was not just one way to live a life. She’s not saying it’s easy, or that it won’t feel like maybe you’re breaking the law, but if you’re brave enough, new structures are possible. The truth is, “You can make it up.”

All Fours by Miranda July is published by Canongate at £20. Buy a copy for £17.60 from guardianbookshop.com. For details of her book tour go to, linktr.ee/allfourstour

Source: theguardian.com